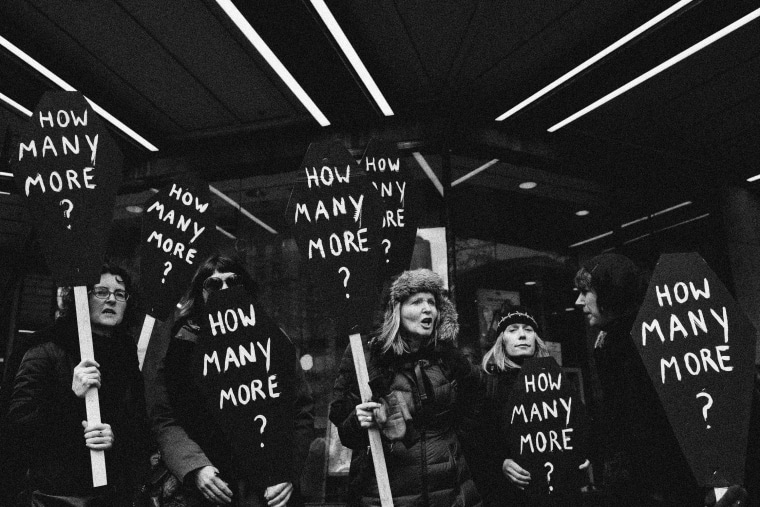

As the youth-led March for Our Lives rallies happen across the nation this weekend to advocate for stricter gun laws, I’m reminded that nothing says “Welcome back to America” like the quiet anxiety that comes with knowing you can be shot doing the most mundane things.

In 2019, this fear that rests just beneath the surface of the consciousness of many living in the United States bubbled up to the surface for me. I returned to the U.S. after five years of teaching overseas. Basking in the glow of being back in my beloved New York City, I walked down 23rd Street. Farther down the block, I saw two men arguing. There was cursing. There was pushing. With each step I took, the tension rose and became clearer.

Nothing says “Welcome back to America” like the quiet anxiety that comes with knowing you can be shot doing the most mundane things.

I was witnessing this squabble a year after students and teachers in Parkland, Florida, had been going about their everyday routines at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School when they became the latest victims of the country’s problem of easy access to guns.

As a result of that shooting, 17 people died and the March for Our Lives organization was created. The group had just organized rallies around the country, so the reality of what “could happen” in the next few seconds, as I inched closer to the argument I was watching, was not lost on me.

“Let me cross this street in case this gets worse,” I thought. Doing just that, I sped up my pace. I secretly prayed that neither of these men had a gun and hoped that if the fight did escalate, it would stay in the realm of disputes I’d witnessed in Asia and Africa. More yelling. Maybe a punch. The end.

I’m reminded of my time abroad and those two men arguing on 23rd Street whenever news of a mass shooting comes — which means I think of them often. As I talked myself out of my fear that I could get shot that day, I remembered how comfortable I’d become while I lived away. When was the last time “I hope no one has a gun” found its way into my thoughts? How long had it been since my stomach tightened because I knew an angry man could shoot me while trying to shoot the man who had caused his rage?

Two months after that encounter, I was sitting in a back-to-school meeting at a U.S. high school where I’d been hired to teach. In the middle of the familiar routines of getting ready for the school year, I was again reminded of the fear that’s become so ingrained into everyday life here.

“Let’s review the active shooter protocol,” the principal said as he pulled up the PowerPoint presentation. I sat there and listened to him remind us to lock doors, keep kids quiet and move them away from windows. “If your room has too many windows,” he stammered before concluding, “well, let’s just hope we never have to use this training, OK?”

Around the room, nervous laughter and heavy sighs covered up the tension I could feel engulfing my colleagues. I looked into the faces of educators and saw a numbness I’d forgotten I once had the last time I had taught in the U.S. The threat of gun violence had become as common as a car accident — or any other awful but regular occurrence.

Another teacher mentioned that if children happened to be in the school library when someone barged in with an assault weapon, they would be more at risk of being killed. The door had no lock. There was no place where all the kids who liked to read books could hide.

We all hoped that the librarian wouldn’t be forced to watch students be slaughtered before she herself was murdered. Then the meeting awkwardly continued. “Let’s move on to planning the assessment schedule,” our principal suggested. We shouldn’t be getting accustomed to these discussions, but somehow we have.

We’ve become so used to murder by firearms that there’s now discussion about how many people must die to even say they were victims of a mass shooting.

This country is not well.

Yes, many countries aren’t, either. The feeling of my stomach tightening as it sensed a vague threat of danger has occurred outside the U.S., as much as it has within its borders. Traveling as a single Black woman all over the world comes with lots of safety concerns.

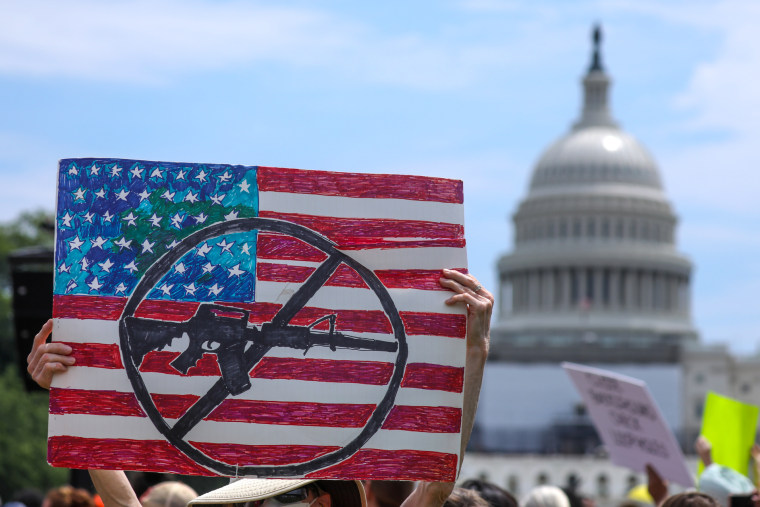

However, what makes our country’s problem of mass shootings so disheartening is how very solvable this distinct danger is. We can’t control citizens’ rage. We can’t control when that rage escalates into violence. We can, however, control how much slaughter results when a violent person decides to subject the rest of us to his anger.

There are more guns in this country than there are people. Depending on where you live in the U.S., buying a gun is akin to walking into a drugstore and picking up a box of Claritin during allergy season. We’re averaging more than 10 mass shootings a week in this country. Furthermore, we’ve become so used to murder by firearms that there’s now discussion about how many people must die to even say they were victims of a mass shooting.

Something clearly must be done, yet lawmakers refuse to vote on gun laws that would do basic things such as increase the age requirement to purchase a firearm from 18 to 21 years or ban assault-style weapons and large-capacity magazines. In the name of freedom, the U.S. has decided to cling to some sort of twisted right to die, to watch children die.

How is this possible when the majority of people in the U.S. are in favor of stricter gun laws? Voters, like myself, are scratching their heads as to why elected leaders can’t act. And around the world, people have come to associate senseless death by firearms with the U.S. It’s come up in conversations with my students in Asia and Africa.

After the 2018 Parkland shooting made international headlines, my students from countries across the globe were again confused about why their American counterparts kept getting killed at school.

“Why doesn’t the country just make laws that prohibit buying guns?” This question came from a Rwandan student who grew up after his country’s genocide in 1994. Its current president made strict laws (prompting critics to accuse him of being an authoritarian) to prevent another massacre. It seemed logical to my student that leaders would make drastic changes to how a country was usually run in the wake of extreme violence.

In China, my eighth grade students proposed the same solution to this uniquely U.S. problem. “It seems like too many of you guys have guns. So, maybe stop letting everybody get a gun just because they want one,” one student said.

I’ve tried to explain the specific sickness my country suffers from on many occasions. And what else can we call it but an illness when something so horrific keeps happening, there are simple solutions that most voters favor, yet our elected leaders refuse to act? I’ve tried to understand it myself. After the shootings in Buffalo, New York, Uvalde, Texas, Chattanooga, Tennessee, and Philadelphia, the ones that happened before and the next ones that will inevitably follow, I’m left with the only explanation that makes sense: We are just not well.