When “The O.C.” premiered in summer 2003, lesbian representation on television was at a weird lull. “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” had ended in May of that year and had killed off Tara — one-half of network TV’s first recurring lesbian couple — a year prior. That was pretty much it for queer girls on teen shows.

Without any gay girls on TV, I successfully convinced myself that “The O.C.’s” Seth was my dream crush and ignored what he really was: at that point, the closest representation of myself I’d seen on TV.

He was a 2000s character archetype I now like to call the Banter Boy.

The Banter Boy is clever. He’s creative, though in his universe his wit goes woefully underutilized. He’s not passionate about his daily life, be it school or work, but his creativity bursts through in fits and spurts, in decorating for made-up family holidays, or penning punk rock songs. The Banter Boy is quick with words, which really just means he’s well written. He’s a stand-in for the male writers of the film or TV show, or at least, it certainly feels that way. There’s an overwhelming sense that the Banter Boy is destined for something great, greater than this rinky-dink town and these small-minded people. Perhaps his most irritating quality is that he, too, seems to know this.

The Banter Boy is skinny with floppy hair, though he exists somewhere on the spectrum of alternative. He looks good in corduroy, and he can wear the hell out of a crewneck sweater. He’s not all that athletic, or at least, his body doesn’t scream athlete. He’s approachable, maybe even explicitly uncool — he’s good-looking because he’s played by a good-looking actor, always, but is somehow deemed not so desirable in the context of his world. It’s confusing.

He’s not a full-on outcast, but the Banter Boy is certainly not in a position of power, nor does he generally want to be. Due to his lack of self-confidence regarding his looks and and inability to shut up, the Banter Boy is an excellent, excellent flirt.

Above all else, he’s a romantic. The Banter Boy always pines for someone out of his reach: the girl echelons more popular than he is, or who’s literal property of a wealthy duke, or who’s been engaged for three years. He’s positioned as the underdog (again: written by male writers). He’s spent years pining over this woman, whom he holds on a pedestal; his crush borders on obsession and is so consuming that all the people around him know about it, except for her.

His crush is so intense that it becomes integral to his self-identity; part of his character, the stuff of who he really is, is about someone else. He’s only a full person in the context of a girl.

On paper, I was much more similar to the boys than I was to any of their objects of affection. They were tall and lanky, like I was. I often wore a blue sweater with a tugboat on it, with corduroys and checkered slip-on vans, an outfit Seth totally would’ve worn to the Harbor School. I was snarky like the boys.

And Seth’s effeminate characteristics get called out on the show all the time. Water polo guys shove Cohen aside, calling him a queer and a f-----. Cohen even read as queer to The Washington Post, which, in their scathing review of the 2003 pilot, described Seth as “a neurotic adolescent who might be gay.”

Indeed, Banter Boys are they kinds of guys who the (archetypically masculine) jocks rail on for being too feminine.

But it’s not that they seem gay, really; their whole character is built around obsessing over a girl, after all. No, the appeal is that the Banter Boy doesn’t seem to be particularly bothered by the gay jokes.

I admired something in the Banter Boy’s quiet self-confidence, despite him being a tad more waifish, a smidge androgynous compared with the rest of his cast; the Banter Boy doesn’t shatter any binaries after all. But I think, as a teenager, I lusted for how the Banter Boy let being called queer roll off his back. It took power away from whoever used the word. On some level, I wished I could thirst over girls with such confidence.

And that’s the core characteristic of Banter Boys: the girls they love. They all pine for girls with boyfriends, who often don’t even know of their existence.

As a teenager, I thought of queerness as something that just defined who you like, not a core essence that exists within you.

Their crushes aren’t circumstantial; no, they’re full-blown personality traits. Love, to Banter Boys, is an independent force that must be adhered to and is ultimately unattainable unless shared with one particular person.

That’s what appealed to me about Banter Boys as a queer kid. Not just the effeminateness or the fact that they liked watching movies alone more than hanging out with hordes of bros. It was the way they were defined by who they loved and how hard they loved them. As a teenager, I thought of queerness as something that just defined who you like, not a core essence that exists within you. Thus, I conceptualized my own sexuality as something that only existed within the context of someone else.

Just like Seth wouldn’t be Seth without Summer, I wouldn’t be a fully realized human being with a sexuality — or a firm identity, really — out of the context of romance. I felt that without enough gay sexual and/or romantic experience, I didn’t really count as gay.

This could’ve come from all kinds of places: the “if you’ve never had sex with a guy, how do you know you’re not into it?” rhetoric, knowing virtually zero openly gay adults, watching characters like Alex Kelly (Olivia Wilde) get toted into Newport Beach to give the show a lesbian kiss and ratings boom then get shipped back from whence she came, only existing in the context of another character.

Did the Banter Boy teach me to be a self-pitying romantic, or was this another piece of myself that I saw in him? Was I mirroring him or relating to him? Self-pitying, over-romantic lesbians have existed for eternity, and will continue to, but it’s probably a bit of both.

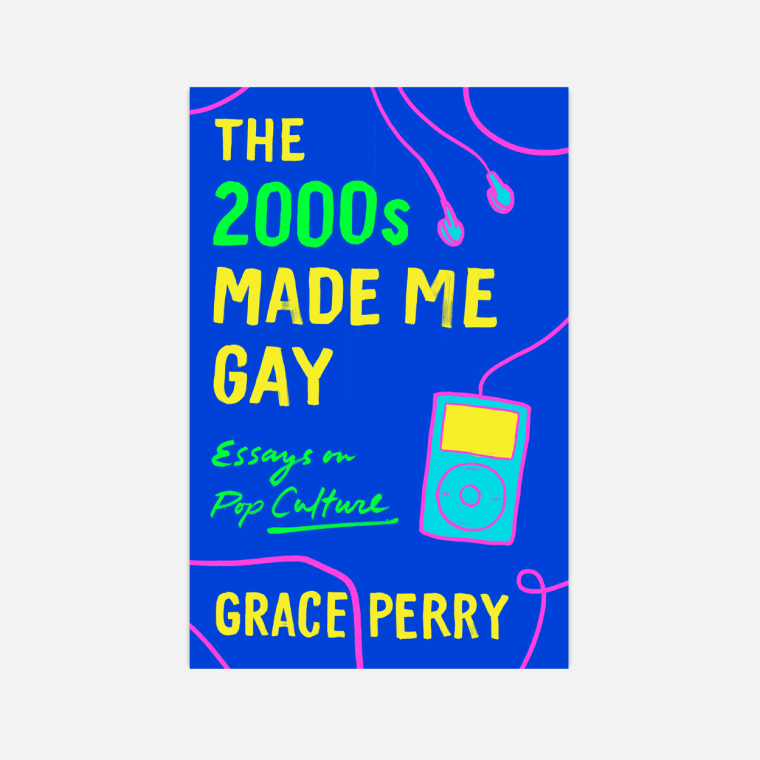

From "The 2000s Made Me Gay" by Grace Perry. Copyright 2021 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Publishing Group.