What is the price of grief? Can you put a value on the communal expression of pain?

This is America in 2020, so the idea that it costs money to feel something isn't as mad as it seems. After all, there's a converted mall in New Jersey that exists only for people to take pictures in. We spend more than $70 billion a year treating depressive disorders. We shell out $2.7 billion on what the National Institutes of Health calls "self care." Why not pay to be sad if it helps you be a little less sad?

Perhaps the real question you want to ask — or that you want to ask someone like me — on the solemn occasion of Kobe and Gianna Bryant's memorial in Los Angeles is: Who pays to go to a funeral? And part of me understands why you would: Dropping, in some cases, over $200 (even if it's for charity) seems like madness.

But then, this is a tragedy that some of us are still struggling to process. Fathers, mothers and daughters perished together — lives lost in an instant for no reason. And, yes, these things happen every day to anonymous strangers who pass through this world without fanfare. When it happens to people who lived their lives in public, it jolts us all out of the complacency of our own lives and forces us to confront how grim and short existence can be.

I'm sure some of the people attending the memorial will go just to say they were there, to hoard some sort of intangible clout for being at a culturally significant event that has a waitlist. But I was desperately trying to find a way to attend the Bryant memorial not to make you think I'm special, but to make myself feel less alone.

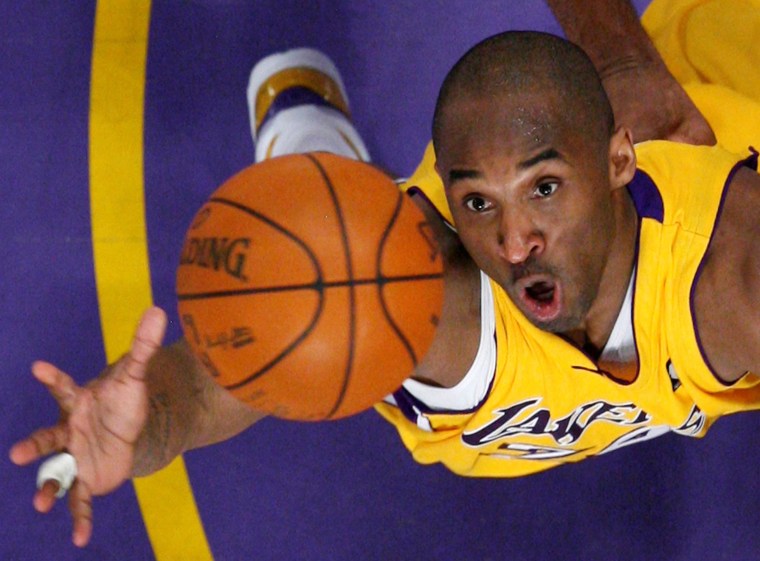

Any money I spent to wander the halls of the Staples Center and recall the moments of joy that Kobe Bryant brought to me and to almost all of us who are there will have been worth it. The greatest societal benefit of sports is that it forces us all together, to experience a feeling — frustration, elation, excitement, boredom — with other people. Athletes let us scream and cry and dream in unison, and Kobe Bryant was one of the greatest athletes of my generation.

It seems strange to me how few people seem to understand that.

Then again, every day, it feels like we as a society are less and less equipped to empathize with someone else's sadness, their anger or their confusion at a world that seems to only grow more mystifying and terrible to all of us. The internet used to be the repository for all of us to vomit the anguish of human existence; personal essays, blog posts and confessionals may have since been widely mocked for how indelicate and shameless they were, skewered as mere vanity and navel gazing, but they were also the closest thing to free therapy to which most people had access.

Facebook, Twitter and Instagram flattened all of that, rewarding their users not for spilling their guts but for monetizing (or allowing major corporations to monetize) overt signifiers of success and happiness — or, worse, barely checked anger.

At its best, the internet can make people feel more connected, but it rarely does that anymore. We couldn't even agree about how sad anyone was allowed to be about the events that took the lives of Kobe and Gianna; John, Keri and Alyssa Altobelli; Sarah and Payton Chester; Christina Mauser; and Ara Zobayan, because of Bryant's fraught legacy.

But sadness is deeply personal, hard to explain and unpleasant to witness; feelings of loss aren't rationally proportioned based on your understanding of an absent loved one's flaws. Grief is isolating, because it's almost always something you have to suffer some part of alone.

My father died in 2006, when I was 22 years old, and I thought my pain was an inconvenience and an imposition to people busy with lives of their own. For someone to take any moment from their day to listen to me blubber through a face full of tears was a kindness I can repay only when that time comes for them.

When my dad had that heart attack — out of nowhere, with no warning and no time to say goodbye — the only full-time emotional support I really had was my family. They were the ones who could relate to what I was feeling, to make me feel less alone. They got why I was so mad at him for not taking his medication, for denying us his life and his presence. They also knew why I missed him in the first place.

If I'm going to have to say a final goodbye to Kobe Bryant — a young man I saw stumble, rise up and grow into the father I hope I can be one day — then I want to do it with the only family that understands this pain: the family of basketball fans who cursed him and cheered him for the 20 years he played the sport on its highest level. I want to know I'm not alone in missing his presence on Earth. That has value beyond money.