Let's talk about the power of romance. There's power in the written word, even in a genre that we tend to consider — because of sexism — less intellectual than some others. And it isn't just about hearts and flowers and candy; this is cold hard cash: Romance as a literary genre represents a quarter of all fiction sales and more than half of all paperback sales, and it brings in over a billion dollars in sales annually.

The impact of romance books on the culture is outsize because everyone is interested in romance, whether they admit it publicly or not.

There’s inevitably a small contingent of writers who simply can’t handle being criticized, whether directly or indirectly.

The business of selling books about love is often handled through the offices of the Romance Writers of America, or RWA. It's the largest writers' organization in the world, with nearly 10,000 members and 150 chapters. Because of those chapters and their dues-paying members, it has about $3 million in the bank, according to its latest publicly available tax filings — which should, in theory, mean that the RWA would be around for years to come.

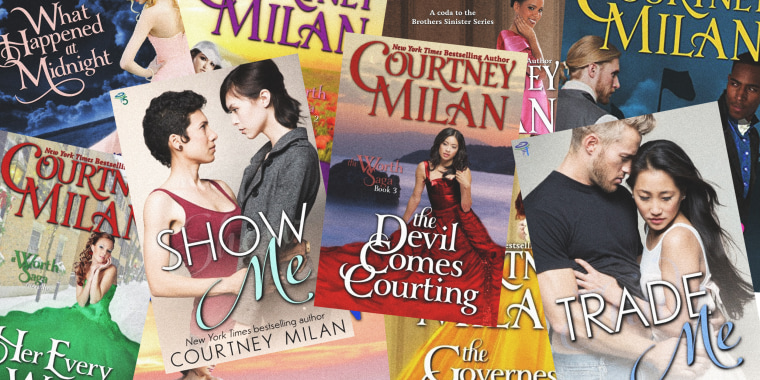

Yet it's been roiled by a series of scandals around inclusion and representation for most of the last decade, all of which have seemingly come to a head since shortly before Christmas. As outlined by The New York Times, that's when the organization's board voted to sanction a prominent Chinese American romance writer and former board member, Courtney Milan, for criticizing on Twitter the novel of a white writer, Kathryn Lynn Davis, as a "racist mess" for its stereotypical portrayals of Chinese women.

The sanctions apparently were considered as part of a secretive process outside the organization's normal ethics procedures, and they would have resulted in Milan's being barred from a board position ever again. As a result of criticism after the incident became public, the sanctions have been suspended, but the firestorm has led to calls to recall the board president, as well as accusations that most ethics complaints go unheard — particularly those by non-white writers — and of favoritism by RWA staff and board members toward white and straight writers.

But if this all seems like a bit of internecine warfare, here is why it matters.

Romance, like much other niche literature, interests readers from all walks of life — and the RWA membership, which is made up of writers, agents and publishers, almost reflects that reality. It should be one of the most democratic professional organizations in the publishing industry, working to grow the genre's readership, especially in a time of flagging fiction sales. You can't, however, do that without appealing to more diverse readers, especially as America itself is changing demographically.

That, at least, has been the attitude of people like Courtney Milan. It's not an uncommon goal; you can find writers from communities that have traditionally been marginalized advocating for access, opportunity and better work in any genre — I've done my share of that work in science fiction and comics — but you can also find readers doing the same. (In fact, perhaps especially in genre fiction, writers are the most voracious readers, and voracious readers sometimes become writers.)

Romance, like much other niche literature, interests readers from all walks of life

But whenever the topic of more inclusion in an industry comes up, it feels like there's always someone insisting that diversity means lowering standards — or that calls for inclusion are bullying, which is essentially what Milan was accused of when she pointed out the racism of Davis' portrayals of Chinese women.

Having been involved in these debates myself, I find it hard not to notice that the people making the most noise against inclusivity are often those who have already put out racist or homophobic work and who strenuously object to their work's being characterized as offensive at all. And though some other authors, when criticized, do pull their books off the shelf for rewrites, most shrug off the criticism or apologize and keep writing books.

Take Nora Roberts, one of the biggest names in romance: In a long statement backing Milan and criticizing the RWA's long history of non-inclusivity, she also makes it clear that she doesn't think her history is perfect, apologizing for the possibility of offensive imagery in a catalog of hundreds of books.

But there's inevitably a small contingent of writers who simply can't handle being criticized, whether directly or indirectly. Vitriolic responses to critics are hardly limited to well-known writers; those who aspire to become household names are equally prone to them. Having your work dissected, discussed and sometimes even demeaned, however, is part of putting it out into the world. All writers know this — or at least they should — and writing romance novels is no exception.

Writers who want to make money, then, often hire sensitivity readers to help them sidestep pitfalls, especially if they don't feel that their agents, editors or publishing houses are up to the challenge. It's just a round of editing that can help a book get more popular and critical acclaim. Critical reaction to flaws in your previous work can serve the same purpose, especially when the conception of who your audience is and what it might accept has changed over time, as it has in the romance genre. So why is there so much anger when people bring up ways writers' work could be better or could appeal to more people?

Well, that's where the cash comes in. Not only is romance big business for those already in it, but the possibility of attracting more readers — and their money — can also make those who think they deserve an audience regardless of the quality of their work antsy about competition from those trying to raise the quality of the industry overall. The complaint against Milan was fundamentally that her criticisms — accurate though they were — had cost other writers opportunities by drawing attention to their flaws. So the real issue isn't whether her criticism about racist elements in other writers' work was accurate, but whether some writers might lose money because of those criticisms.

This is about writing, but it is also about our culture and whether we want the people who have traditionally influenced it to continue to do so without engaging with the consequences their work might visit on other communities. Everybody wants a little romance; what most people of color who read about it don't want is romance novels written by white authors filled with stereotypes about people of color. If the RWA isn't looking out for its non-white (non-straight, non-cisgender) readers' interests, then it's not helping any of its authors — and it's not spending its members' money particularly wisely.