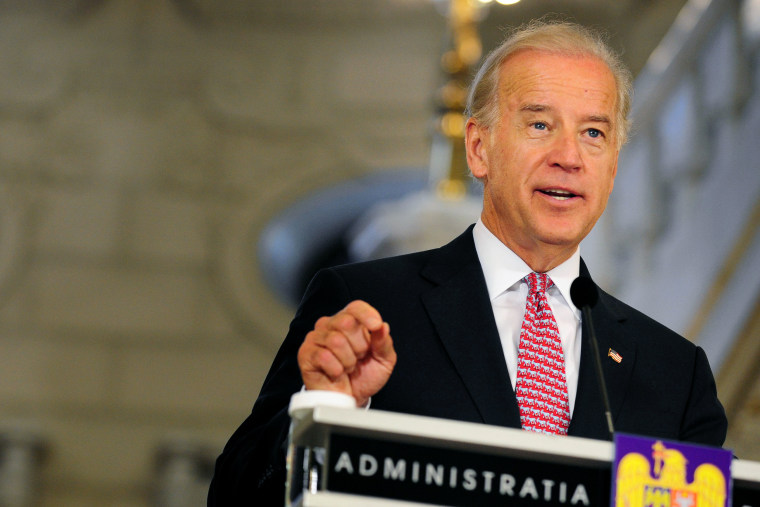

In 2009, about a year into his vice presidency, Joe Biden was in Romania, giving a speech about the importance of NATO solidarity. I was there with him, as a young advance guy paying more attention to Biden’s punctuality and the order of European flags on the stage than to the speech’s strange geopolitical moment.

As Biden’s speech was simultaneously translated into 15 languages, his primary preoccupation was to rally his audience to America’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

At the time, hardly anyone was preoccupied with the possibility of Russia’s invading a European country. In the decades after the Cold War, much of central and Eastern Europe was growing more prosperous and democratic. So as Biden spoke — and as his speech was simultaneously translated into 15 languages from across the region, including Ukrainian — his primary preoccupation was to rally his audience to America’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

There’s been a lot of news lately about NATO’s Article 5 — the provision that compels each member country to respond to an attack on an ally as though it had been attacked itself. In the treaty’s 70-year history, however, the article has been invoked only once: after the 9/11 attacks on the U.S. In retrospect, as an analyst of U.S. foreign policy who has come to understand NATO as effectively a vehicle through which the U.S. guarantees European security, it was surreal to watch the vice president of the world’s strongest country thanking Romanians and Poles and Czechs for their service in these Middle East wars.

In that 2009 speech, Biden addressed critics who thought the U.S. was no longer focused on central and Eastern Europe. But he didn’t exactly deny the criticism. “It's precisely because of our global responsibilities and your growing capacity and willingness to meet them with us that we value our partnership,” he told the assembled diplomats and officials from across the region. In other words, the U.S. valued this region for its support in our wars — but mostly took its stability for granted.

As countries like Hungary and Poland today confront ethnopopulist movements and democratic backsliding, Biden’s hope back then — that their “sustainable progress” might “help guide Moldova, Georgia, Ukraine along the path of lasting stability” — seems almost quaint. According to polling by my organization, the Eurasia Group Foundation, support for American ideas of democracy has dropped in Poland in the past three years from 72 percent to 48 percent. In our most recent poll, just 19 percent of Poles described their country as “very democratic.” While the U.S. isn’t primarily to blame for European countries’ recent political challenges, it certainly hasn’t helped matters.

While the U.S. isn’t primarily to blame for European countries’ recent political challenges, it certainly hasn’t helped matters.

In Ukraine specifically, the Trump administration tried to slash the budgets for pro-democracy programs and requested deep cuts in nonmilitary aid. Russia expert Anatol Lieven told me in a recent podcast episode: “If you look at the figures for U.S. aid to Ukraine since 2014, among all this talk of support and future NATO membership, U.S. levels of economic aid to Ukraine were frankly pitiful. Pitiful, and that ain’t solidarity.”

Making matters worse, pro-Trump social media bots have previously spread conspiracy theories about anti-corruption reformers in Ukraine. As one of the bot army’s targets told The Economist in 2019: “It is the first time we have been hit with such a well-organized smear campaign from America. We are used to that coming from kleptocrats here in Ukraine.”

Today, as Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy presses Congress for more military aid, it’s worth considering how technical and economic support for nonmilitary initiatives might have put Ukraine in a stronger position (and how continued military aid might make the war more deadly and destructive). After all, political and economic corruption have largely doomed Ukraine’s NATO ambitions. As Biden told a group of Ukrainian officials in a 2014 visit, “You have to fight the cancer of corruption that is endemic in your system right now.” Had the U.S. spent as much energy in this region deepening its commitment to democracy as it did broadening its security commitments, it paradoxically might have strengthened Ukraine’s bid to join the NATO alliance — a membership that might have stopped Russia’s takeover ambitions.

But should NATO membership have been dangled before Ukraine at all? Biden’s speech in Romania more than a decade ago was delivered a year after NATO pledged at a summit, held in the same city, that Ukraine and Georgia “will become members of NATO” in the future. Moscow ominously condemned this promise to the two former Soviet states on its border as a “huge strategic mistake.” Just last week, Zelenskyy recognized that Ukraine realistically had no immediate path to membership. This was interpreted as an “olive branch” for diplomatic negotiations with Russia. With the benefit of hindsight, using the promise of security guarantees as an incentive for democratic reform seems ill-considered.

As I stood backstage at his speech in Bucharest, I heard Biden insist this region has shown itself “ready for our common challenges, willing to tackle them and able to overcome them” so “we no longer think in terms of what we can do for Central Europe, but rather in terms of what we can do with Central Europe.” It’s a nice, Kennedy-esque thought and an important aspiration: In the decade since the speech, the U.S. has rightly sought to rebalance the role it plays in Europe’s defense through increased burden-sharing — i.e., getting its allies to invest more in their own military might (the subject of NATO’s less famous Article 3). But at the time, such characterizations were, at best, wishful thinking and, at worst, reflective of a careless disregard of the region’s true military capabilities and political challenges.

As he appeared to give up hopes on NATO membership specifically and deeper European integration more generally, Zelenskyy suggested last Tuesday that NATO countries wouldn’t, in fact, come to one another’s aid if Russia’s aggression spread to them. “Article 5 of the NATO treaty has never been as weak as it is now,” he concluded. Despite polling by my organization (and others) that finds Americans roughly split over the use of the U.S. military to repel the hypothetical Russian invasion of a Baltic NATO ally, Biden continues to insist the U.S. will defend “every inch of NATO territory” with the full force of U.S. power.

Let’s hope we don’t have to find out who is right. One thing is certain: The U.S. will not soon be ignoring this part of the world or taking its security for granted, as it did on that day in 2009.