We are in an era of increasing partisanship. The Pew Research Center found that since 2016, Republicans and Democrats have grown more frustrated with each other. Commentators worry that tension between the two parties could soon make democracy unworkable. If Republicans see Democratic victories as illegitimate, for example, could a defeated President Donald Trump refuse to leave the White House? Would his party support him?

If Republicans see Democratic victories as illegitimate, could a defeated President Donald Trump refuse to leave the White House? Would his party support him?

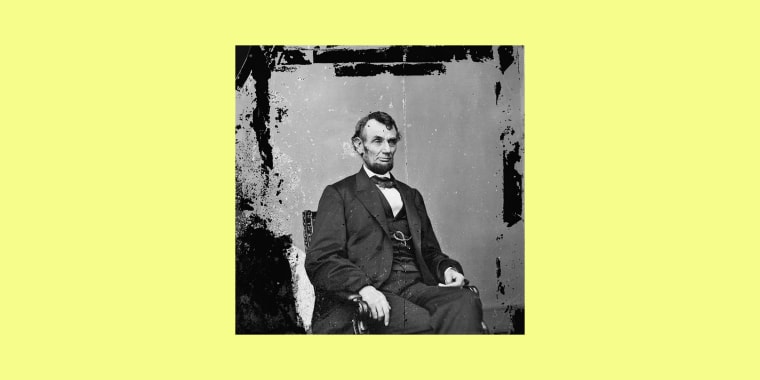

A presidential election has led to a crisis once before. After Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln won in 1860, Southern Democrats refused to accept him as president. Two months after the election, South Carolina became the first state to secede from the union. Nathan P. Kalmoe's new book, "With Ballots & Bullets: Partisanship & Violence in the American Civil War," is an examination of how partisan commitments and division led to violent conflict in the 19th century. It illustrates some of the worst aspects of partisanship. But it also, surprisingly, shows how partisanship can be valuable and even necessary.

It's easy to see the dangers of partisanship in the 1860s. And as Kalmoe points out, America's very bloody Civil War was preceded by decades of escalating partisan violence, often around elections.

Parties had their own groups of "toughs," who tried to intimidate the other parties' voters; electoral riots and fights injured many and killed a handful of people in the 1830s and the 1850s. Partisan tension in Congress was so high that representatives often carried guns or knives to defend themselves, Kalmoe writes, and there were a number of open brawls. In 1856, Democratic Rep. Preston Brooks of South Carolina severely beat Sen. Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, an antislavery Republican, with a cane in front of colleagues.

Despite this strong record of polarization, historians have often downplayed the role of partisanship in the Civil War. In this interpretation, people voted for Republicans when the war was going well and for Democrats when it wasn't.

In the summer of 1864, for example, the war was going poorly, and Republicans feared that a public sick of defeat would toss Lincoln out of office. Then Gen. William T. Sherman won a resounding victory at Atlanta in September. Lincoln's landslide re-election in 1864 seemed to many at the time and since then to be the result of that military success.

But by analyzing House elections in 1864, Kalmoe uncovered a different story. In the 1860s, congressional contests were held over the course of the entire year, rather than on the same day as the presidential contest. If Republicans were in trouble before September, House GOP candidates should have been crushed by Democratic challengers. But instead, Kalmoe found, Republican vote share changed little over time. Lincoln was on his way to win before Atlanta. Republican partisans supported the president even though the war was going poorly, as they did when the war was going well.

In the Civil War era, partisanship had a strong effect on how people interpreted good or bad news.

In the Civil War era, partisanship had a strong effect on how people interpreted good or bad news. That shouldn't be a surprise, Kalmoe told me. You can see this in public response to Trump's handling of COVID-19. FiveThirtyEight tracked polls from March to mid-July and found that partisan approval of Trump's response barely changed; Republicans consistently gave him around 80 percent to 85 percent approval, while Democratic voter approval dropped from around 27 percent to 10 percent. "The same folks who liked him before think he's doing well, while those who disliked him before see how disastrously he's performed," Kalmoe said. COVID-19 is "a monumental event, yet partisans haven't moved more than an inch so far."

Republican refusal to abandon Trump seems ominous. Trump's disastrous response to a national health crisis has led to tens of thousands of unnecessary deaths. If his voters aren't moved by that, how can we hold government accountable to the people at all? Partisanship seems to be a recipe for denial, dysfunction and death.

But, Kalmoe told me, it's important to remember that "partisanship can be leveraged for good or bad purposes." During the 1860s, partisanship rallied Democrats to the cause of slavery and treason. But it also led Republicans to make great sacrifices for the Union even when the war seemed to be going against them. It ultimately pushed many Republican voters to support the abolition of slavery.

Similarly, partisanship today has rallied resistance and opposition to the Trump administration. Democratic voter turnout surged in 2018, when the party took the House back from Republicans. Intention to vote in 2020 among Democrats was at 70 percent in April, 9 points higher than in 2016, according to a Reuters poll. Voting intention remains high as of mid-July.

Democratic voters in Wisconsin even risked their lives when Republicans refused to postpone an election in April during the pandemic. Anger at Republican intransigence led Democrats to vote in large numbers despite the virus. "People wanted to fight back with everything they could," Wisconsin Democratic Party Chairman Ben Wikler told The New Yorker. And so they did, handing Republicans a stinging defeat in a key state Supreme Court contest.

Partisans are stubborn and recalcitrant. They can be willfully blind and violent. But Kalmoe's book is a reminder that partisanship also was a key factor in allowing the Union to resist and fight disunion, racist treason and slavery. Pro-Lincoln partisanship, Kalmoe told me, was necessary to combat "partisan violence in service of evil — in this case, reinforcing slavery and rejecting legitimate elections." Similarly, Trump is buoyed by partisanship. And if we're going to defeat him, we'll need partisanship to do it.