On April 26, the White House presented a "testing blueprint," an addendum to the Guidelines for Opening Up America Again announced two weeks ago. It came after weeks of pressure from public health experts and state leaders asking for a national testing strategy.

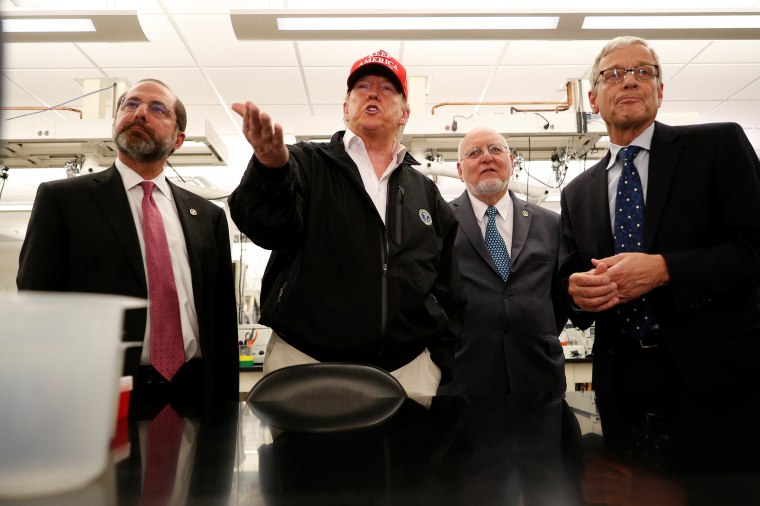

The plan is an important step — in fact, it's the first comprehensive acknowledgment by President Donald Trump and his coronavirus task force that we need to do better on testing. But just like the earlier guidelines, it falls short on the details. States have been asked to develop their own plans and rapid response programs, and urgently needed national coordination remains elusive.

The plan is an important step — in fact, it’s the first comprehensive acknowledgment by President Donald Trump and his coronavirus task force that we need to do better on testing.

People ask why this is so important. Obviously, we need more tests — that's old news. People are working on it. Why do we keep talking about it?

In fact, we've been talking a lot about the economic toll of keeping stay-at-home orders in place — and the president himself has tweeted his desire that various states be "liberated" — but why reopening the country too quickly may backfire has been less fervently discussed. And the No. 1 reason the United States is shut down, the reason our economy is in turmoil and why our death toll is so high, as over 67,000 Americans have died, is that we are so woefully behind on testing.

We began falling behind in January and February, when the virus was spreading, but we didn't test for it at all because of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's faulty initial testing kit. In February, a complicated Food and Drug Administration process stalled private labs that were ready to test. And then, in March, as tests slowly became available, we saw assurances from the White House that "everyone who wants a test can get a test," when, in fact, very few people who needed a test could get one.

It is now early May, and the need still far outstrips the availability. The more we fail to test adequately, the more we play catch-up with an incredibly fast-spreading virus.

The Guidelines for Opening Up America Again ask states to move through the plan's phases for opening depending on their numbers of cases. Yet the only way to know the true number of cases in any state is by implementing ubiquitous, on-demand testing.

When we can test broadly and get results quickly, we can identify those who are infected and are potential sources of transmission to others. Pairing testing with contact tracing and isolation, we can separate those who are infected, limiting the spread of the disease. We know how we got to shutting the country down, so to end social distancing and open the economy, we will need a lot more testing.

For weeks the U.S. stalled at 150,000 tests daily. Now we are reaching around 200,000 daily tests, which is an improvement — but not nearly where we need to be. In large parts of the country, testing is still limited. Most people with mild symptoms aren't tested and are, instead, told to quarantine at home. Their contacts are rarely tracked, and no proportion of relatively healthy asymptomatic people — those who have the virus but don't know it because they have no symptoms — is tested at all.

Our research shows that testing capacity must increase to at least 500,000 daily tests to open up the country. This is a conservative estimate, compared to others who argue that we will need millions of tests daily. Broken down to state levels, these numbers vary, since the size of the outbreak is different from state to state. From a testing point of view, some states are more ready to open up than others.

Increasing our testing capacity to at least nearly 4 million tests a week is difficult but possible. Here's how it could be accomplished.

Increasing our testing capacity to at least nearly 4 million tests a week is difficult but possible. Here’s how it could be accomplished.

The most commonly used test right now is called RT-PCR, which looks for fragments of the virus, often from a nasal swab sample. While there is some debate about whether this old and slow technology can deliver the number of tests we need, it can certainly be scaled up and get us much closer to our testing goal.

Several factors prevent a greater number of RT-PCR tests: Shortages of swabs, materials and reagents continue to plague many states and must be addressed. New testing machines, recently approved by the FDA, can perform rapid PCR tests, but so far there are only a few of them.

Ironically, while many states lack adequate testing capacity, some states have ample or even excess supplies. In these instances, loosening testing guidelines would allow us to start testing more people with mild COVID-19 symptoms.

Other COVID-19 testing technologies are under development, some quite far along. Serology testing, which looks for an immunologic response to the virus, can be helpful in assessing whether a person has previously been infected. Other tests offering quick results directly at the doctor's office, including immunodiagnostics that look for the presence of the viral antigen from throat swabs — similar to the screening test done for influenza — are in development and may at some point become readily available.

Given the urgent need to open up our economy soon, we must take an all-of-the-above approach to expand our testing capacity. And in the absence of a national strategy, states need to take the lead.

States that are doing better on testing and flattening the infection curve, such as Utah and New Mexico, have one thing in common: They have identified senior leaders to serve as testing coordinators and oversee rapid expansion of testing capacity. More states should do so.

Testing coordinators can focus on identifying and tackling state-specific barriers, whether they be swab availability or ensuring an adequate testing infrastructure. They can also work with the federal government to move supplies as needed — for example, if one state is short on swabs but has extra machines to run the tests, they could exchange with a state with plenty of swabs but limited test machines. Needless to say, federal coordination of such efforts would be very helpful.

As states prepare to open up again, we are at a critical juncture in our national response to the pandemic. But let's not forget how we got here — by tragically underestimating the importance of testing for COVID-19. The clear course of action to slow this disease, save lives, rebuild our economy and try to avoid an even worse shutdown in the fall must be: testing. More testing and more effective, timely testing. Tracking and then even more testing.