Recent criticism of President Donald Trump’s attempt to coerce Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy into investigating the son of former Vice President Joe Biden, a top political rival, has led to a flurry of allegations of corruption in American politics. Despite the rhetoric, however, the U.S. is not a very corrupt country, and the discrepancy between corruption’s reality and our perception can only damage rather than strengthen our democracy.

The most accepted definition of corruption is the misuse of public office for private gain, meaning that corruption entails evidence of illegality while serving in a public office and the exchange of something of material value. In American public discourse, however, corruption stands in for all of our displeasures with politics.

While in America a billionaire may become president, elsewhere presidents become billionaires.

Conflating corruption with distasteful political activities is dangerous. The charge of corruption is a serious one that deserves equally serious evidence. When we start to attribute our problems to corruption, it not only makes the charge of corruption meaningless, but also degrades the stability of democratic institutions, sows alienation and distrust, and diverts resources away from curtailing illegal abuses.

Corruption as defined in law is extremely rare, and the accusation that influence-peddling represents a legal form of corruption is no more than a complaint about democratic rituals, human nature and the common workings of even the cleanest and most transparent organizations.

Social, economic and political problems are damaging interpersonal relations, political participation and our country’s global influence much more significantly. Yet since 2015, Chapman University surveys have consistently shown that Americans are more fearful of corruption than any other issue. Likewise, a 2014 Gallup World Poll found that 75 percent of Americans believe that corruption is widespread. A 2018 Kaiser Family Foundation poll identified that concerns about corruption cut across party lines, worrying Democratic, Republican and independent voters nearly equally.

We choose to focus our attention on corruption rather than actual entrenched problems because corruption is a convenient scapegoat for other social and political faults. Indeed, it is much easier to blame an anonymous corrupt elite than ourselves for our societal and political shortcomings.

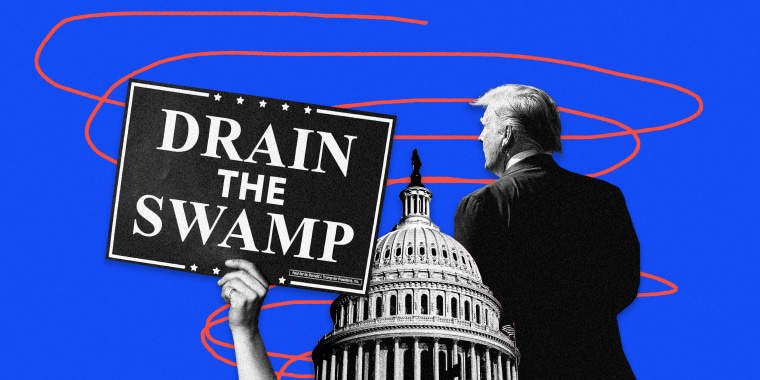

Of course, politicians and the media know how concerned we are about corruption and feed the obsession. Trump, for instance, defended his conversation with Zelenskiy by arguing that he was asking for Ukraine’s help in his fight against corruption. Meanwhile, many of the Democratic candidates have developed anti-corruption platforms for their presidential campaigns. And mentions of corruption by news outlets grow with every passing year.

As a consequence, one might think that corruption is devouring our country. But in reality, corruption poses a negligible threat to the United States. Transparency International found in 2013 that although almost 8 in 10 Americans believed that corruption was widespread, fewer than 7 percent of Americans had actually encountered bribery, by far the most widespread form of corruption.

Some might argue that corruption in the United States is limited to and, indeed, widespread in political circles. In politics, however, official Department of Justice data shows that federal corruption crimes have steadily declined since the early 1990s and remain constant at state and local levels. Perhaps, then, American corruption is mostly corporate rather than political? Again, the data reveals that white-collar crime prosecutions are at their lowest levels in recent history even as more resources are devoted to rooting it out.

In contrast, much of the world faces serious problems with corruption, bureaucratic dysfunctionality and lackluster political accountability, leading to what amounts to a tax that disadvantages the middle class and the poor. Imagine the feeling of a vulnerable, hospital patient in China who has to pay bribes to their doctor or risk improper medical care. In Vietnam, traffic stops routinely lead to bribes rather than fines. In Algeria, the route to receiving government contracts is paved with kickbacks.

Indeed, much of the world encounters corruption at levels that Americans cannot comprehend. Consider the fact that while in America, a billionaire may become president, elsewhere presidents become billionaires, accumulating vast wealth by stealing from their country’s natural resources, budgets and foreign aid.

While instances of corruption, even if rare, can reduce mass trust in politicians, the consequences of believing that occasional scandals amount to a nationwide corruption crisis are far worse. In fact, it is sometimes better to accept corruption’s inevitability than to exaggerate it.

Exaggerating corruption erodes democracy. Fear of corruption makes people vulnerable to false prophets who favor severe anti-corruption tactics.

First, exaggerating corruption erodes democracy. Fear of corruption makes people vulnerable to false prophets who favor severe anti-corruption tactics. Sociologist Jean Lipman-Blumen finds that tyrants prey upon our need for authority, security and belonging, as well as fears of ostracism and powerlessness. Indeed, anxiety over corruption may damage our well being, thus contributing to our collective thirst for leaders claiming a supernatural ability to fix our problems. As political scientist Samuel Huntington once cautioned, “antagonism to corruption may take the form of the intense fanatical puritanism characteristic of most revolutionary and some military regimes.”

This assessment is borne out by the way many anti-corruption populists are today destroying democratic institutions in the name of fighting corruption. Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro reflects fondly on the anti-crime policies of the country’s former military dictatorship, including torture. In India, Narendra Modi’s party is applying political pressure to the Supreme Court in the name of fighting judicial corruption. Rodrigo Duterte advocates for extrajudicial killings of corrupt police officers in the Philippines.

Moreover, worrying about corruption leads people to retreat from political life, lose faith in democratic institutions and distrust one another. One study shows that voters who are aware of a political candidate’s corruption not only retract support for that candidate but become less likely to participate in elections. Another finds that perceptions of widespread corruption in a country can lower trust in public institutions, such as the police, political parties and the legislature. And in overestimating how bad corruption is, we ignore other serious, underlying problems.

Our goal should not be to “end corruption,” a rallying cry of the president, his opponents and international organizations that inflates expectations and then makes us resentful of politicians when they are unable to reach this lofty goal. Rather, the aim in the U.S. should be to keep corruption to a low level, with a careful rather than panicked devotion of attention and resources to the issue.

America has an advantage in this effort: While not perfect, we have proven ourselves to be skillful managers of corruption on several fronts. The news media holds leaders accountable; the legal system continues to enforce robust anti-corruption laws; and law enforcement agencies regularly pursue nonpartisan corruption investigations against foreign and domestic actors. The capacity of American institutions to fight corruption was evident when Trump reneged on his self-enriching decision to host the 2020 G-7 summit at the Trump National Doral of Miami resort after mass outcry.

Even maintaining existing low levels of corruption requires extensive tools of accountability, however, and there are some cracks in our accountability mechanisms. Trump’s interest in weakening the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and his decision to repeal a Securities and Exchange Commission financial disclosure rule for oil and gas companies are reasons for concern. Sweden’s agency devoted entirely to anti-corruption efforts produces results that exceed many other countries — and provides an example for how we can improve. But there is little reason for panic.

In taking measured steps and tempering our expectations — and our fears — we free up energy to fix the serious problems that threaten our democratic institutions, and defend ourselves against charismatic despots who use our fears of corruption against us.