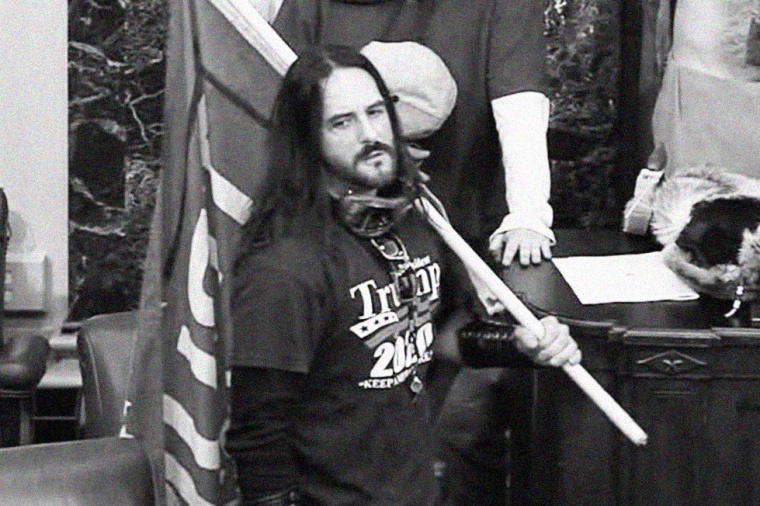

Tampa resident Paul Hodgkins, who was photographed marching onto the Senate floor during the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol, was sentenced to eight months in federal prison last week.

He got a huge break.

It’s not likely to happen to other convicted Capitol rioters.

Hodgkins’ sentence was lighter partly because he pleaded guilty. But something else was missing from the case.

Hodgkins’ sentence was lighter partly because he pleaded guilty. But something else was missing from the case — an aggravating factor present in many of his fellow defendants’ cases.

First, Hodgkins took the well-traveled path taken by other famous infamous criminals, such as Michael Cohen, or Felicity Huffman. He raced to court and pleaded guilty as fast as he could, to get the best possible deal. In the highly-structured federal sentencing scheme, pleading guilty early earns an offender valuable bonus reductions.

Hodgkins admitted that he committed the crime of corruptly obstructing and impeding the certification of the Electoral College vote count, which was an “official proceeding” under the law.

On one axis of the federal sentencing chart is the gravity of the crime the defendant committed. On the other axis is the defendant’s criminal history, which is almost as important as the crime itself. A defendant with no criminal history can expect to be in the lowest category of sentencing for that particular crime. In federal sentencing, it’s good to be what they call a “zero.” Hodgkins and his lawyer agreed with the government that his crime warranted a sentencing range of 15-21 months under the federal sentencing guidelines.

Had Hodgkins not accepted responsibility, his sentencing range would have been 24-30 months. (Defense attorneys complain this is really a “trial penalty”: if a defendant exercises the constitutional right to trial, he won’t get that “acceptance of responsibility” bonus.)

But either way, Hodgkins got just eight months, which is seven months under the lowest end of the guideline range of 15 to 21 months. So how, and why, did that happen?

First, the “how?” In 2005, the Supreme Court held that mandatory sentencing guidelines violated a defendant's Sixth Amendment right to a jury trial. That decision rendered the sentencing guidelines advisory, and just one factor among several that district courts consult.

A court may now sentence below — or above — the guidelines, as long as the court thinks it is necessary to achieve a sentence “sufficient, but not greater than necessary” — whatever that means.

Next, the “why?” Courts must avoid unwarranted sentence disparities among defendants with similar records who are guilty of similar conduct. But there really is no such thing as “similar conduct” here, at least not from a historical perspective. Even the prosecutors in Hodgkins’ case conceded that the Jan. 6 crimes are unprecedented. They defy comparison.

With nothing to compare it to, the judge in this case had a lot of discretion.

The prosecutors argued to the court that to try to mechanically compare other defendants charged under this statute prior to Jan. 6, “would be a disservice to the magnitude of what the riot entailed and signified.” The prosecutors also admit that “Hodgkins is one of the first to be sentenced, and thus, there is no apt comparison.” With nothing to compare it to, the judge in this case had a lot of discretion.

Maybe Hodgkins’ argument swayed the court here. He said he only walked into the Capitol an hour after the Congress had recessed. He said he was just following the crowd. He said he did not have any direct contact with law enforcement. He said he neither touched nor damaged anything inside the Capitol. Maybe that helped.

More likely it was this: According to his lawyer, Hodgkins did not go onto social media to brag about his involvement in the riots. If so, he avoided the unofficial “galactic stupidity” sentencing enhancement (my term). This unwritten penalty booster does not appear in the sentencing guidelines. But it is directly related to the rise of social media and cameras in everyone’s phones. Defendants who celebrate their crimes with selfies or online posts can expect judges to often impose harsher sentences. No one will have much sympathy for them.

If convicted, the other Capitol defendants who preened about their crimes on social media should not expect a “below-guidelines” sentence like Hodgkins got. It’s very possible Hodgkins’ reduction is one that federal law doesn’t recognize yet: the absence of moronic online behavior.