White supremacists and their ilk have long used propaganda as a tool to spread their message. Long before the internet, men stood on corners with paper bags of hateful flyers or drove from town to town, leaving their racist or anti-Semitic photocopies on front steps and in driveways.

This tried-and-true tactic is now back with a vengeance. In 2019, U.S. white supremacists employed paper canvassing of neighborhoods and college campuses more than at any time in recent memory, with an unprecedented number of flyers, banners, stickers and posters appearing across the country.

In 2019, U.S. white supremacists employed paper canvassing of neighborhoods and college campuses more than at any time in recent memory.

But the age-old scourge is being accompanied by some innovations, including a technological upgrade. The propaganda is used to lure potential haters online, where these new recruits are gradually indoctrinated more and more. And given the negative publicity surrounding violent rallies like Unite the Right in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017, white supremacists have chosen to temper their rhetoric. That means their posters and stickers may initially appear to be innocuous, making their propaganda tactics even more insidious.

According to our research at the Anti-Defamation League, white supremacists were responsible for 2,713 propaganda distributions across the United States in 2019, an increase of 123 percent from 2018. Dozens of white supremacist groups participated in this barrage of offensive propaganda, which was documented in every state except Hawaii.

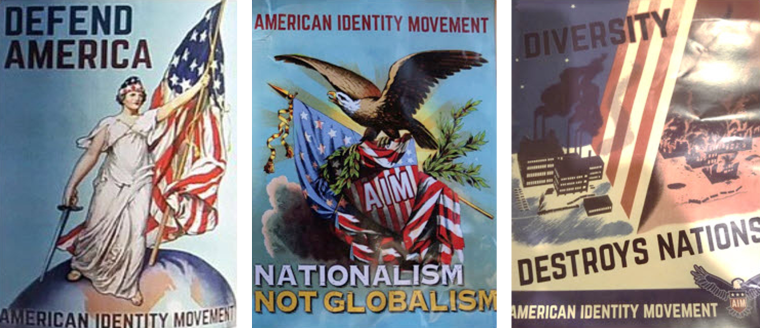

Three white supremacist groups are overwhelmingly responsible for the increase: The Patriot Front distributed the most, with the American Identity Movement and the New Jersey European Heritage Association trailing in distant second and third.

These and other white-supremacist groups largely favor veiled hate over explicitly racist language, and some, such as the Patriot Front, lean heavily on “patriotic” imagery, incorporating American flags or red, white and blue color schemes. They all tend to use toned-down language about how “diversity destroys nations” and the need to take pride in “Western” culture.

This is purposeful; it gives white supremacists an opening to a population of curious young people who would most likely be turned off by explicit neo-Nazi rhetoric or overtly racist language.

And it provides a greater chance of their signs passing under the radar instead of being immediately challenged. A poster encouraging passers-by to “Defend America” or urging “Nationalism Not Globalism” probably wouldn’t raise many eyebrows, while it might attract a few curious young people to visit the website printed in tiny letters at the bottom edge of the placard.

Because white supremacists are still worried about the impact of public exposure in the wake of Charlottesville, they’ve learned to take advantage of social media, starting with paper but quickly following up online. As soon as a poster is taped up, for instance, a photo appears on a white supremacist group’s social media feed proudly noting the propaganda and its location.

Members of white supremacist groups can post these “patriotic” flyers anonymously or hold and quickly disband flash demonstrations before counterprotesters can assemble. They then share their images and videos, knowing they’re finding their audience. They create fear and anxiety in communities with little or no risk to their reputations.

While the language may be intentionally vague, it does the job. It’s a hat-tip to those who recognize and embrace “globalism” as an anti-Semitic trope and other such hate-filled dog whistles, but it also serves as a more subtle invitation to people with no established ties to extremism whose curiosity may have been piqued by an offhand comment or an intriguing phrase.

But it’s not just the words or images on the poster or sticker that matters — it’s also the placement. White supremacists target locations where they know they’ll have an impact: campus multicultural centers, Hillel buildings and African American studies departments.

That’s part of the hateful message: We’re here, and we’re watching you.

White supremacists haven’t completely abandoned public demonstrations, either. Even with the increased risk of exposure, there were 76 white supremacist events in 2019, by the ADL’s count. Members of the three leading propaganda-generation groups attended the deadly 2017 Unite the Right rally, and earlier this month, roughly 150 masked Patriot Front members marched through Washington. Still, these events are usually held at night or out of public view.

Public or not, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed in the face of these events and rising numbers, but there are steps we can take to respond to this explosion of propaganda.

We can start by recognizing white supremacist messaging for what it is and speaking out against its dangerous bigotry. Communities nationwide should view these propaganda incidents as opportunities for learning, for speaking up and for actively rejecting this growing trend. Every time that happens, we’re all a little bit stronger.

And while these fliers are protected as free speech, that doesn’t mean we have to simply accept their presence — on campus or off. Campus leaders and administrators should send a strong message that universities are places for learning, not for spreading hatred and fear.

Administrators should be transparent in sharing information about incidents with the entire campus community and in explaining how the message on the flyers is anathema to the campus community.

Communities nationwide should view these propaganda incidents as opportunities for learning, for speaking up and for actively rejecting this growing trend.

Campuses can help by training student leaders, resident advisers and others in positions of authority to recognize hate groups’ calling cards so these flyers can be removed as quickly as they pop up.

When propaganda appears elsewhere, such as on doorsteps or car windshields or public bulletin boards, it is important not only for community leaders to condemn it, but also for law enforcement to be fully informed about such incidents.

Flyers and other hateful activity can warn of more serious acts, so it’s essential that the public know who is behind this propaganda, and why they pose a danger to society.