Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., wants a political revolution. Former Vice President Joe Biden wants to beat President Donald Trump.

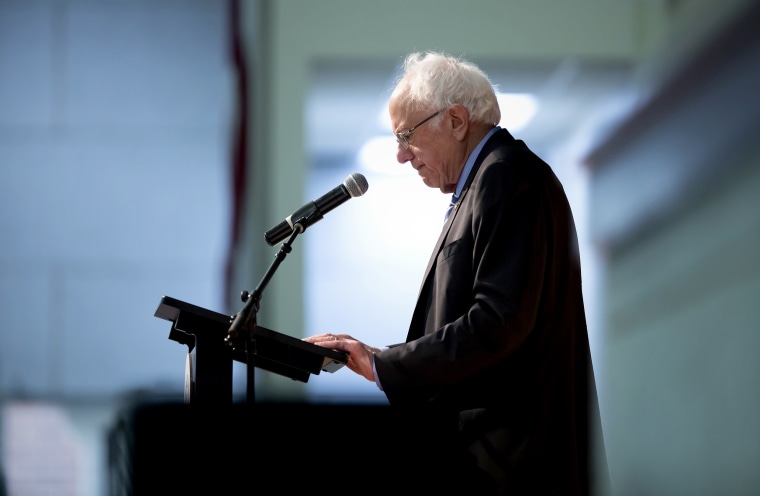

Biden’s vision has now won out: He is the apparent Democratic nominee after Sanders suspended his campaign Wednesday following a mid-pandemic Wisconsin primary marred by vast polling site closures and a U.S. Supreme Court ruling that effectively invalidated many absentee ballots. (Sanders said Monday, given the risks to voters, his campaign would not engage in traditional efforts to get them to the polls.)

His announcement, however, came weeks after Biden effectively clinched the nomination by cleaning up on Super Tuesday (March 3) and in several big-state primaries a week later.

Biden’s win isn’t exactly a testament to his astounding political skills: He’d formally run for the nomination twice before, in 1988 and 2008, and failed after gaffe-filled campaigns both times. In his first run, Biden didn’t even make it to the 1988 primaries, dropping out in September 1987 amid plagiarism charges. In 2016, Biden finished fifth in the Iowa caucuses and dropped out the next day, having never really recovered after dismissing then-rival Sen. Barack Obama as “the first sort of mainstream African American who is articulate and bright and clean and a nice-looking guy.”

Thus, in 2020, Biden was only a viable candidate because he’s a former two-term vice president for a still-popular former president.

His primary cycle victory, then, reflects his appeal among broad swaths of the Democratic base, the moderate-leaning nature of the broad Democratic electorate and voters’ single-minded focus on defeating Trump in November. This all points to what will likely be a tough but winnable campaign against Trump between now and Election Day.

And in particular, his decisive win over Sanders in the primary — without even campaigning in many states — further highlights the limitations of progressive politics in America, at least in winning a national campaign.

Sanders, a self-described democratic socialist, made a bad bet on the existence of a national progressive majority (as did Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., who ran as a progressive populist but dropped out after Super Tuesday). It turns out there's nothing even close.

In fact, it’s not even clear that a progressive majority exists within the Democratic Party. What does exist is a moderately center-left party with a vocal progressive element.

Sanders frequently said on the campaign trail that he was leading a “multigenerational, multiracial movement,” pledging to mobilize an army of new, young voters. But it turns out older and moderate voters are the ones that grew as a share of the Democratic primary electorate since 2016 — and they favored Biden by a wide margin.

Take the South Carolina primary on Feb. 29, which Biden won, or the 10 of 14 states he captured on Super Tuesday: In all, he appealed to the same coalitions that boosted Democrats so strongly in the 2018 midterm elections, turning out large numbers of suburban voters, while maintaining support from longstanding elements of the Democratic coalition, particularly African American voters.

Or look at Florida, where Biden crushed Sanders, 62-23 percent, in the March 17 primary, winning every county in the process. According to exit polls, Biden won overwhelmingly among voters ages 40 and up and, while Sanders did win voters under age 30, he didn't do so nearly at the rate he needed to seriously challenge Biden's dominance in other categories.

And ideologically, 50 percent of the Florida Democratic primary voters called themselves “moderate” or “somewhat conservative,” while only 22 percent called themselves “very liberal” and 19 percent “somewhat liberal” — again putting Sanders' thesis that there is a silent progressive majority waiting for a candidate to marshal them to the polls in question.

Primary voters' choices also showed the limits, even among Democrats, of Sanders’ call for Medicare for All, which would effectively banish private health insurance in favor of a government-run program. Here, Sanders was treading on what everyone, for good reason, believed was fertile ground: Health care was the issue that registered voters nationally considered the most important, according to a Hill-HarrisX poll taken Dec. 8-9, 2019.

But Sanders’ plan, it seems, was not exactly the voters' preferred solution: Kaiser Family Foundation polling in 2019 repeatedly showed that a majority of Democratic and Democratic-leaning voters preferred reforming the Affordable Care Act, implementing a public option or a Medicare/Medicaid buy-in than Medicare for All (and 67 percent of Medicare for All supporters mistakenly believed they would keep their own health insurance were it implemented). Sanders' early Democratic primary rivals, Warren and Sen. Kamala Harris of California, each initially embraced versions of Medicare for All but quickly retreated when it became clear that voters weren’t interested.

Biden consistently criticized Medicare for All as unrealistic and outrageously expensive and pushed instead for an expansion of the Affordable Care Act — the signature domestic achievement of the president he served.

On a range of other issues, too – climate change, immigration, college affordability, tax policy – Biden’s agenda was more centrist and more popular among Democratic primary voters than Sanders', while Sanders insisted that his vision represented a majority of the Democratic coalition.

That’s not, of course, to say Sanders didn’t have an effect on the politics of the race. Since becoming the increasingly apparent Democratic nominee, Biden has moved to the left on some issues, including speaking favorably of Warren’s bankruptcy plan — a significant change from their clash at a 2005 Senate hearing when she was a Harvard Law School professor and he represented Delaware, the state that’s home to the U.S. credit card industry. Recently Biden also backed a proposal by Sanders that would make tuition free at public colleges and universities for families with incomes under $125,000.

Still, with the 2020 Democratic primary process essentially over, it’s clear that the hard-core Democratic left was deluded in their assertions that they were the new Democratic majority. They are going to need a better grip on reality if they are to be successful at the national level moving forward.