On Monday, The Washington Post published its investigation into the history of U.S. slaveholders who have held congressional office. The Post’s discovery that more than 1,700 members of Congress held people in bondage at some point in their lives is in many ways unsurprising.

Somewhat more surprising are revelations of the ubiquity of slaveholding across the partisan political spectrum and the enduring presence of former slaveholders in Congress for many decades after slavery ended in 1865. These realities demonstrate that fully accounting for slavery’s influence on American life requires extensive political and chronological range.

Between 1789 and 1819, even as some states ended slavery or provided for its gradual abolition, five new slave states entered the Union.

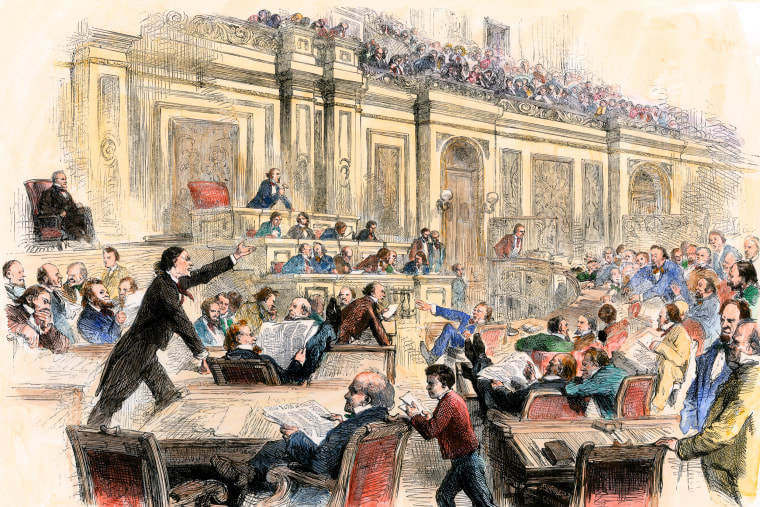

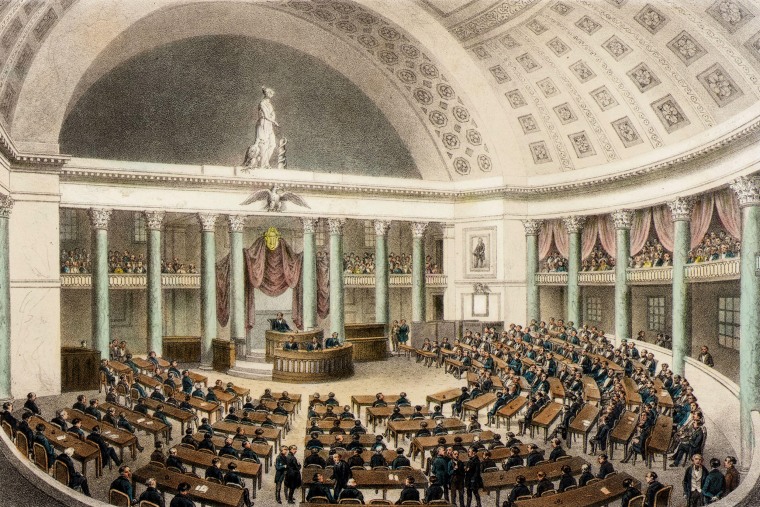

We might well anticipate the prevalence of slaveholders in Congress in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. After all, slavery was recognized by every one of the original 13 Colonies, and slaveholders made up nearly half the delegates to the Constitutional Convention. That gathering protected, and in some ways enhanced, slavery’s power in the national framework that would govern the United States. Between 1789 and 1819, even as some states ended slavery or provided for its gradual abolition, five new slave states entered the Union, and slaveholders made up the majority in every Congress but one.

Slavery, and the number of slaveholding representatives, dwindled or disappeared in Northern states in the decades before the Civil War. But it expanded in Southern states, and the political might of slaveholders in those states remained formidable. Through most of the period between 1820 and 1850, over 40 percent of members of Congress still held or had held people in bondage.

Political party divisions with regard to slavery, however, were not nearly so clear as geographic ones. Our histories typically, and rightly, identify the Republican Party in the 19th century as the party of Union and abolition and the Democratic Party as the party of secession and slavery. But the Post investigation pointed to a more complicated political history. The largest number of slaveholders in Congress indeed affiliated with the Democratic Party: Of the 1,715 slaveholders the Post identified, 606, around 35 percent, were Democrats. But 481 slaveholders, roughly 28 percent, were Republicans for at least some portion of their political careers.

The Post also found that elected members of more than 60 different political parties enslaved people. Some belonged to what were once major parties but have since ceased to exist, like the Federalists and the Whigs. Still others belonged to short-lived parties that were largely absorbed into the 19th-century major party system, like the Anti-Jackson and the Anti-Masonic parties, or to third parties like the Populists, Prohibitionists and the nativist American Party.

To be sure, the politics of some slaveholding members of Congress shifted over time. There were slaveholding Whigs who became Democrats as the Whig Party disintegrated and the Democratic Party emerged as slavery’s leading political champion, and there were slaveholders of varying stripes who either turned against slavery before the Civil War and became Republicans or determined after emancipation that their political prospects would be brighter by aligning with the Republican Party. But correlating slaveholding with party identification eludes nearly every simple or straightforward narrative.

Importantly, neither does slaveholding map perfectly onto anything like what we might today consider “conservative” or “liberal.” It was slavery’s very pervasiveness in American society and American politics, in fact, that confounds such efforts. Though incompatible with the ideals of some American politicians, believing in or benefiting from enslaving other people could be made to fit a wide range of political perspectives and partisan identities.

Importantly, neither does slaveholding map perfectly onto anything like what we might today consider “conservative” or “liberal.”

Moreover, while slavery came to an end with the end of the Civil War and the ratification of the 13th Amendment, many (now former) slaveholders returned to political office and sat in Congress for generations. The number of slaveholders in Congress dropped precipitously during the Civil War as most slave states withdrew from the Union, falling to a bit more than 10 percent in the Congress that met from 1863 to 1865. When the war concluded, however, that percentage began rising again, such that nearly 20 percent of members of Congress in the late 1870s and early 1880s had once been slaveholders. They dwarfed the number of members who had themselves once been enslaved, and they continued to help make federal policy as it applied to the newly emancipated people and their descendants.

These lawmakers were elected overwhelmingly from former slave states. But they were not exclusively so. West Virginia, which came into being as a free state during the Civil War, sent nearly half a dozen former slaveholders to Congress after the war’s conclusion. Illinois had a former slaveholder in its congressional delegation in the late 1870s, and congressional delegates from the western territories of New Mexico, Wyoming and Utah had enslaved people before the war, as well.

The number of slaveholders in Congress made its final decline during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as those who had enslaved their fellow Americans aged and died. But Congress would not see its very last slaveholder until 1922. Appointed to a Senate seat and sworn in for just a single day after a sitting senator died, Rebecca Latimer Felton of Georgia was born into a slaveholding family and married a slaveholding doctor and planter. Well after slavery had ended, she remained a devout white supremacist and an advocate of lynching. Though slavery was long in the past by 1922, its presence in Congress had by then already lingered for generations.