Majority culture in America tends to portray skin color as a binary: You either have light skin or you have dark skin. The reality, though, is that skin color is a spectrum. And frankly, most people of the African diaspora fall somewhere in the range of colors that, in the post-Rihanna makeup-line era, we canonically refer to as from Fenty 340 to Fenty 498.

So, why do media depictions tend to highlight those with lighter skin and looser curl pattern in their hair? It’s not uncommon to hear song lyrics — "Lightskin" by Tyga, "Better Things" by A$AP Rocky, or "PARTYNEXTDOOR" by Recognize featuring Drake — about the beauty of Black girls who fall somewhere in the Fenty 200 to 330 range.

That is why, perhaps, it’s not surprising that Beyoncé’s new song, “Brown Skin Girl,” has struck a nerve.

Although Beyoncé has never shied away from claiming her Blackness, her last several projects have also explicitly embraced Black culture. Beyonce’s lyrics in “Formation” — “My daddy Alabama, momma Louisiana. You mix that negro with that Creole, make a Texas bama” — speak specifically to her experience as a member of the African diaspora in America. In “Lemonade,” she not only incorporated the poetry of Somali-British poet Warsan Shire, but also worked with imagery from Yoruba folk tales, utilized the work of Nigerian artist Laolu Sanbanjo and makes references to Nefertiti, Malcolm X and Kenyan traditions. With “Homecoming,” she paid homage to the historically Black college experience that she didn’t have but clearly values.

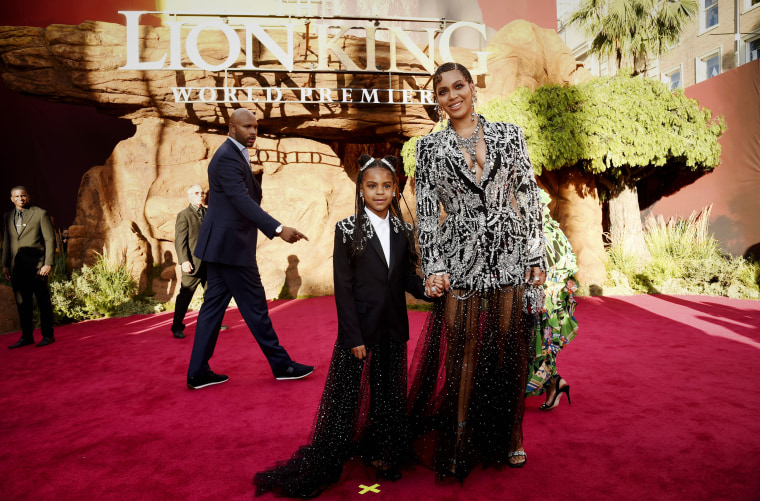

Now, with “Brown Skin Girl,” she has gone a step further, specifically highlighting the beauty of those women, like her daughter Blue Ivy, who could never pass a paper bag test.

The paper bag test was a practice in some American clubs, churches and other community organizations — including some African Americans ones — of holding a brown paper bag against the skin of a would-be entrant. If you were lighter than the paper bag, you passed the test and were welcomed; if you were darker than it, you needed to stay out. It was sometimes imposed by white gatekeepers, as was the case of the white gangsters in charge of New York’s Prohibition-era jazz clubs; but colorism existed in and was enforced by African American communities as well.

Though the test is no longer explicitly happening in public, the impact of colorism persists: Studies show that the privileges associated with having a lighter skin tone range from greater success in school and the workplace to a lower likelihood of being arrested, and shorter jail sentences.

To some extent, Beyoncé has benefited from light-skinned privilege, though she is still visibly of African descent in a majority white society. But what makes “Brown Skin Girl” so meaningful to dark skinned Black women in particular is that it celebrates not just brown skin in general but dark brown skin in particular, when anti Blackness has normally meant that, even in communities that are ostensibly battling the same issues around skin color, there is a clear bias specifically against the most visible Blackness.

This song specifically highlights the beauty of those who fall into that shade range known as “deep” in so many makeup brands, citing Beyoncé’s former Destiny’s Child bandmate Kelly Rowland, supermodel Naomi Campbell and Oscar-winning actress Lupita N’yongo as examples of dark-skinned “Brown Skin Girls” to directly challenge the idea that dark brown skin is less beautiful than lighter skin tones. And, in the last two verses, Beyoncé specifically addresses her own daughter, Blue Ivy (who sings the intro and outro of the song): “Your skin is not only dark, it shines and it tells your story,” she sings, “If ever you are in doubt, remember what mama told you.”

Yet when you look at the reactions to this song, it’s clear that many don’t want to engage in any critical thinking around colorism and its impact on girls like Blue Ivy and the women they grow into, much less anti-Blackness in their communities. When the hashtags #BrownSkinGirl and #BrownSkinGirlChallenge hit Twitter, tags like #WhiteSkinGirlChallenge popped up — whether created by trolls or not, they speak to the idea that celebrating one kind of beauty inherently means denigrating another.

Even some within the diaspora had a knee-jerk reaction because the song specifically named women darker than them. But there’s no insult in celebrating the most disenfranchised members of a community, no harm in not centering those with the most power and privilege — and nothing wrong with teaching your beautiful daughter to see her beauty in a world that you know might not celebrate it as vociferously as it has your own.

We know that representation matters, that it is important for young girls and women to not only see people that look like them succeed, but also to hear that they have worth and value. But it’s easy to claim that beauty standards are shallow and that no one should care about looks when you’re not the one consistently being told by society that your skin color makes you ugly.

I’m a Fenty 410 or 420 (depending on the time of the year), but even I know that I benefit from some colorism — not as much as someone who is lighter than me, but just as skin tones come in a spectrum so does privilege. “Brown Skin Girl” carves out a place for Black beauty in a culture that often situates beauty as being about proximity to whiteness, and it does so without relying on any fetishizing or demeaning of the rest of the diaspora.

For once, a piece of media celebrating our unique beauty exists. Enjoy it. It doesn’t need to be about you. After all, we’ve been singing along to songs not meant to be about us all this time.