Ever since a former reality television star captured the Republican presidential nomination and then the White House, American politics has taken on a stranger-than-fiction quality. The usual expectations that were built on generations of punditry and prognostication often no longer hold, and nowhere has this been more apparent than by where the Democratic presidential primary stands in the wake of Super Tuesday. Joe Biden’s campaign roared back to life after it should have been long dead following stinging losses in Iowa, New Hampshire and Nevada — in fact, it had already been buried by much of the pundit class.

Over the course of 72 hours, a political revival that would have made Lazarus proud unfolded before us: Biden crushed his competitors in South Carolina, and the party’s relative moderates coalesced around him in short order. Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar, acrimonious foes to the end, both suspended their presidential bids and threw their support to the former vice president. A who’s who of Democratic stalwarts also rushed to endorse him, from the youthful Texas icon former Rep. Beto O’Rourke to party elder and ex-Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid.

The Democratic Party today is cohesive in a way that the GOP has not been since at least 2016.

What we now know, without having to rely on forecasters, is that the longtime Delaware senator and enthusiastic glad-hander now boasts an edge in delegates over the former Democratic front-runner, Bernie Sanders. Second, the consolidation of the party’s centrist wing and African-American base behind Biden had a decisive role in determining Tuesday’s outcome. Third, even at this time of populist fervor, the Democratic establishment can still signal its preferences to voters to materially affect the behavior of the party rank-and-file.

This last point may come as a surprise to many, especially after the failure of Republicans to halt Donald Trump from capturing their party’s nomination the last time around despite the popular conception that the Grand Old Party has had more control over the rank-and-file than Democrats. However, the Obama-Biden wing of theDemocratic Party has long been more robust than the establishment wing of the Republican Party, at least when confronting Donald Trump.

That influence is still apparent, especially after former President Barack Obama decided to pick up the phone and talk to Buttigeg. The former president reportedly did not specifically ask for the former mayor of South Bend to endorse Biden, but the implication was clear.

This tells us that the Democratic Party today is cohesive in a way that the GOP has not been since at least 2016. In contrast with the inability of Republican powerbrokers to stop Trump four years ago and settle on a more mainstream nominee, the Democratic Party remains an independent power source — and counterweight to some of its adherents’ most extreme inclinations — that will be a factor through the rest of the primary and general election process. The punditocracy would be wise not to discount it just because the GOP crumbled under the pressure of Trump’s ascendance.

In 2016, the GOP apparatus was effectively leaderless and reviled after having lost two presidential elections in a row. Former President George W. Bush commanded some respect, yet there was little meaningful deference among the party faithful when it came to the presidential nominee, in part because of his relatively low approval ratings in the ranks after the failures of the Iraq War and the financial crises. For some of these same reasons, Republicans were also deeply ambivalent about the GOP’s policy agenda.

That ambivalence was on full display with the seemlingly swift abandonment of his brother Jeb during the 2016 race, and that, combined with the party’s misunderstanding of the pro-Trump populist phenomenon, allowed the New York real estate mogul to win the nomination largely by disavowing the Bush program of foreign war, free trade, and entitlement reform.

Democrats, on the other hand, regard Obama as a transformative leader, a perception only enhanced by the contrast with his White House successor. In his post-presidency, particularly among party leaders, he’s seen as the Michael Jordan or Babe Ruth of American politics. Despite his vulnerabilities and errors, he guided the United States out of a recession, pulled off the Herculean feat of passing a sweeping expansion of social protections in the form of the Affordable Care Act — oh, and his administration saved the auto industry and killed Osama Bin Laden

That creates a legacy of continuing regard and support for the party elders, Obama chief among them, but also those who represent the continuation of his. And accordingly, there remains a widely embraced policy agenda, all of which means both voters and down-ballot candidates are more inclined to follow their lead.

Democrats, whatever our squabbles, understand in our bones that the country is on the line this fall — at the very top, but also up and down the ballot.

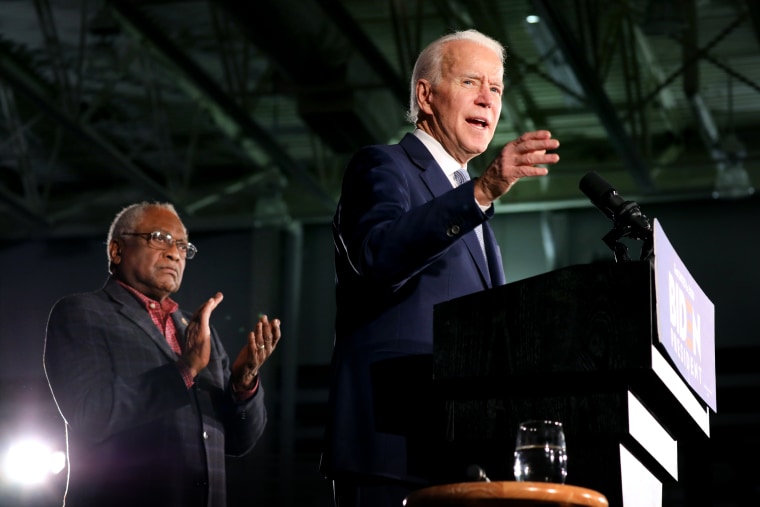

Biden has an undisputed claim to this legacy and affection as essential to the numerous accomplishments of the Obama presidency. So do party notables like Reid and House Majority Whip James Clyburn. Democrats trust these veterans, and that showed as Biden — who was outspent seven-to-one by Sanders and who barely made a personal appearance in any of the states participating in Super Tuesday — rode to victory on three elusive and priceless assets: virtually universal name ID, a great reputation and the aforementioned goodwill of the party.

In South Carolina, exit polls showed that 47 percent of primary voters said Clyburn’s late support for Biden was an important factor when entering the voting booths, if not the most important factor. Biden’s success in the early Southern state came directly from the beloved Clyburn and African-American voters. It wasn’t a machine or a deal in a smoke-filled back room. It was, however, smart politics.

Behind the abrupt withdrawal of Klobuchar and Buttigieg, some Sanders devotees are bound to see a palace coup carried out by party bosses. Needless to say, a push by a popular past president is not a coup — it is reminding self-interested candidates, who might be caught up in the moment or the adulation of their supporters, what the voters really want and what is most likely to lead to victory. But even in the heyday of the brokered convention and the smoke-filled room, Democrats were mostly inept at engineering such events. Will Rogers, riffing on this fractiousness and unruliness a century ago, memorably quipped that he belonged to no organized political party because he was a Democrat.

Watching the transformation of the the Republican Party over the last four years has shown Democrats exactly what not to do.

No, the explanation is far more pedestrian. Democrats, whatever our squabbles, understand in our bones that the country is on the line this fall — at the very top, but also up and down the ballot in swing districts and states throughout the country — and that this is a time when we will either stand together or hang separately. Of course, the decisions by Klobuchar and Buttigieg were spiced with a dose of what they personally wanted, too. Neither had a plausible path to the nomination, and neither wanted to see Sanders take on Trump.

I would like to think that Democrats would never have embraced the type of candidate that the Republicans did in 2016, but what we see now is that no one candidate is going to stand in the way of what’s best for the party — and more importantly, best for the country. At the very least, watching the transformation of the the Republican Party over the last four years has shown Democrats exactly what not to do.

As a result, here’s what we saw: The top finisher in Iowa, the candidate with the strongest record of winning with the swing voters needed to prevail in November and the candidate with by far the most money all suspended their campaigns with a singular goal of defeating Trump. The Democrats of 2020 are nothing like the Republicans of 2016. Thank goodness for that.