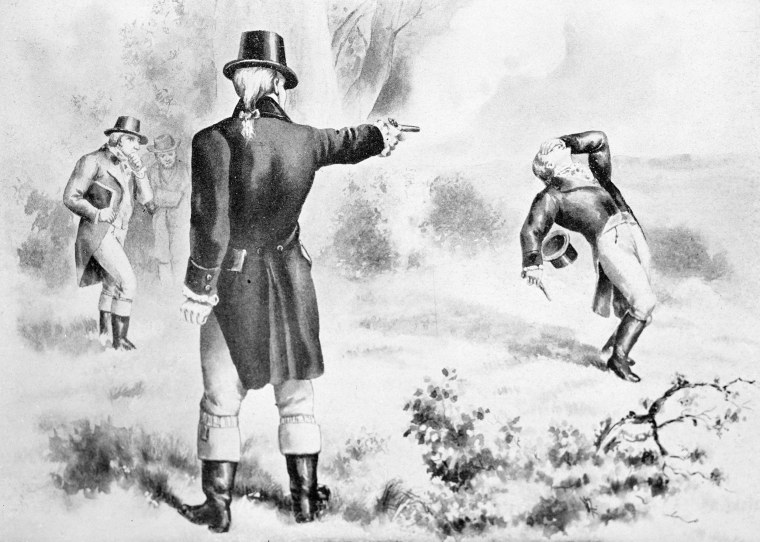

Thanks to the Broadway musical "Hamilton," most people today know that Vice President Aaron Burr shot former Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton on the Weehawken dueling grounds in New Jersey in 1804 after a long, bitter political rivalry. Some people, however, may be surprised to learn that Burr may have later regretted his actions — and the partisanship that inspired them.

Only a few years before he died, according to Ron Chernow's definitive biography of Hamilton — and despite numerous earlier accounts from contemporaries and even family members that, to that point, he had shown no remorse over Hamilton's death — Burr seemingly eventually recognized that he needn't have been so bothered by Hamilton. Upon reading a scene in Laurence Sterne's novel "The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman," in which the titular character's kind Uncle Toby catches and then releases a fly, Burr is (perhaps apocryphally) said to have remarked: "Had I read Sterne more and Voltaire less, I should have known the world was wide enough for Hamilton and me."

Sterne and Voltaire, of course, were both popular European writers and philosophers of Burr's youth. But whereas François-Marie Arouet — known by his nom de plume, Voltaire — often wrote in polarizing succeed-or-die-trying language, Laurence Sterne was an Anglican clergyman who used satire and comedic writing to advance acceptance and tolerance.

Upon learning of Burr's late-in-life reflection, it made me question who influences my own thinking. I realized that whom I choose to listen to will, whether I like it or not, greatly affect how I see the world.

If a late-in-life Aaron Burr could see the effect of Voltaire's polemics on his own thinking, then modern-day advocates of extreme partisanship could be having an effect, as well.

However, in this day and age, the information and people that influence me won't always be chosen by me at all. According to a Pew Research Center Report, a staggering 55 percent of Americans now get their news from social media, and, as Anthony Breznican wrote for Vanity Fair in August, social media companies are "deepening [our] biases and blind spots by pushing away everything else."

Filmmaker Jeff Orlowski told Vanity Fair in the same article that social media apps are specifically designed to feed us whatever keeps pulling us in, making our digital realities completely different from our real lives, in which we would normally be confronted with more diversity. "We are actively building systems that are causing polarization, that are causing echo chambers, that are dividing our country and our way of thinking," he says.

So, in a manner of speaking, if someone today reads or watches what one Voltaire type says on Facebook, Instagram or YouTube, the company's algorithms will bombard that person with posts and videos from numerous like-minded Voltaires, all reinforcing the same ideas — and it will also minimize the number of Sternes they see. The algorithm thinks that watching or reading one thing about a topic means you will be interested in seeing more about it, so it serves as much of that to you as possible, all to keep you watching or scrolling.

I've seen this play out among my conservative friends.

Take, for instance, Candace Owens, a right-wing commentator and political activist; her views are extreme, to put it mildly. Some things she says might occasionally have broad merit, but nearly everything seems designed to charge up the radical right and provoke outrage from the left. She once said that being asked to wear a mask during the pandemic amounts to tyranny. She said she didn't have a problem with nationalism, even in Germany: "But if Hitler just wanted to make Germany great and have things run well, OK, fine. The problem is that he wanted, he had dreams outside of Germany." And more recently,she said Harry Styles' sartorial choices in a magazine spread were "an outright attack" on men and pleaded on Twitter: "Bring back manly men."

Whom I choose to listen to will, whether I like it or not, greatly affect the way I see the world.

But she's effective at what she does on social media: A friend of mine loves her commentary so much that she highlights pages from her book and shares them on Instagram as if they were from the Holy Bible.

And when I see friends sharing her quotes and views on social media, I grow concerned — because I know that similar far-right personalities will soon start popping up in their news feeds, as well. Sure enough, a day or two later, the same friends begin sharing similar sentiments from other radical personalities to whom Facebook and Instagram have just introduced them.

It seems reasonable to me that, if a late-in-life Aaron Burr could see the effect of Voltaire's polemics on his thinking, then modern-day advocates of extreme partisanship could be having an effect on modern-day disciples, as well.

I could, of course, pull similar examples from the left, which has radical personalities of its own — all of whom are just as motivated to rile up their followers, which social media sites will promote to keep users scrolling and watching. And I'm not suggesting that there be more censorship of people's general political views by social media platforms.

Seek out your Sternes, because no social media company is going to do it for you.

But I am asking us to consider what effect these corporations' deliberate amplification of many radical influencers is having on our society.

Just recognizing the reality can be helpful. Orlowski says it comes down to "keeping in mind that there is somebody on the other side of that political ideology that disagrees and is not seeing your side of the conversation — and is probably being reinforced with their own thinking and their own views."

What's more, knowing we can manipulate the algorithms trying to manipulate us helps, too: You don't have to be beholden to whom social media sites think you should read or watch. Follow politicians and commentators from both sides of the aisle — doing so will both help you learn more about what those with whom you disagree are seeing and ensure that your social media streams will be filled with at least some measure of moderation.

Seek out your Sternes, because no social media company is going to do it for you. After all, the history lesson here is not that Burr read Voltaire too much — but that he didn't read Sterne enough.