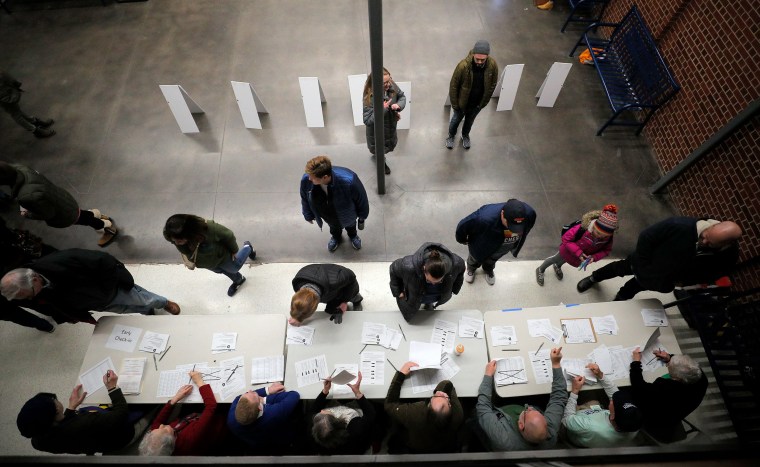

This is probably not how the Democratic Party wanted to begin its presidential primary process. The freak-out over the delayed results out of the Iowa caucuses Monday night has revealed just what a wire-and-string effort collecting and tabulating the vote can be, and how little it takes to raise doubts about the integrity of the election process.

With nine months until Election Day, we need to learn from Iowa — and fast. If something like this happens in November, the fallout is going to be far, far worse. And it may well happen, given continued concerns about vulnerabilities in our election security system (even though there has been considerable progress recently). Election administrators, journalists and political parties need to be prepared. They should be developing plans as of yesterday.

With nine months until Election Day, we need to learn from Iowa — and fast. If something like this happens in November, the fallout is going to be far, far worse. And it may well happen.

Election integrity has been on the minds of Americans since 2016, when we now know that Russian operatives infiltrated at least seven states. That’s one reason Democrats were pushing hard last year to get more money for election security and were disappointed when Congress only allocated $425 million, far less than the $2.2 billion that some election experts say would be needed for state and local governments to meet their basic security needs.

Between 2000 and 2012, the share of Americans who said they were confident that the country’s vote was being counted fairly plunged from about 50 percent to 20 percent. This was mostly driven by Republicans, whose confidence fell dramatically. Between 2016 and 2018, the share of Americans overall who thought computer hacking was a major problem more than doubled, from 17 percent to 38 percent. And nearly three-quarters of Americans (and 90 percent of Democrats) are worried about Russian meddling in elections.

Add in widespread Democratic concerns about voter disenfranchisement and widespread Republican worries about voter fraud, and it’s easy to imagine that absent a clear winner and very smooth reporting in November, the 2020 election could bring some kind of legitimacy crisis.

This is dangerous territory for a democracy. It’s even more dangerous when the 2020 election is likely to be very close, and a few screw-ups or distortions in a few states could be pivotal. And it’s even more dangerous when you have an incumbent president who has repeatedly claimed Democrats engage in voter fraud and has said at least 27 times that he would like to stay in office beyond constitutional limits.

The mess in Iowa — in which the count of a small number of voters in a small state in just one party’s nominating contest took nearly a day to start to be announced because of failures in a new vote reporting app, allowing for the outcome to be muddied and easily challenged -- plays directly into the hands of President Donald Trump or Russia or anyone who might have a vested interest in charging that the national election process is unreliable.

Many writers have been asking questions about the possibility of whether Trump will refuse to accept defeat in 2020. As Georgetown University law professor Joshua Geltzer has explained on CNN.com: “Trump's unrelenting assaults on the media and intelligence community, augmented by his baseless insistence on widespread voter fraud, have laid the groundwork for him to contest the election results in worrisome ways by undermining two institutions Americans would count on to validate those results.”

And Democrats already harbor many skeptics about their own party mechanisms. According to a new Voter Study Group report by John Sides and Robert Griffin, “about a quarter each of Biden (24 percent), Warren (25 percent), and Buttigieg (28 percent) supporters said that they were not confident that the 2020 Democratic primary was being conducted fairly. More than one-third of Sanders supporters (37 percent) said the same.” Those numbers, of course, came before Iowa.

The amount of election-related litigation has tripled since 2000 (which itself was a highly litigated election), University of California at Irvine law professor Richard L. Hasen notes in his new book, “Election Meltdown: Dirty Tricks, Distrust, and the Threat to American Democracy.” In a close election with any procedural uncertainties, we should expect both sides to push as many legal fights as they can afford to fund. In short, a fusillade.

One lesson that the Iowa delay already makes clear is that any uncertainty around electoral reporting is a social media void into which massive conspiracy-mongering will flow, especially among those who have something to gain by pushing the narrative of a broken system.

Similarly, because news coverage has to fill the extended wait time with drama, narratives of delay can quickly spiral into narratives of confusion and chaos. As Stanford University law professor Nathaniel Persily noted on Twitter, “elections can be ‘hacked’ by undermining confidence in results even when voting technology works fine.” That is, once a narrative of bedlam spreads, it can be hard to pull back.

This is an important lesson for the press, whose analysis will shape how voters respond to any irregularities. Reporters and headline writers who use words like “confusion” and “chaos” to draw clicks should think about the distrust they are sowing.

Likewise, all election administrators should have a plan in place to manage public expectations if they encounter irregularities, and they should be actively educating reporters on what to expect.

What can be done? Right now, there is no Plan B, so we need to get one fast.

Here are two ideas. One, the Democratic National Committee and the Republican National Committee could jointly appoint an independent expert to certify results in a disputed election rather than leaving it to the traditional ad hoc judgments of secretaries of states and court challenges — a process that is almost certain to exacerbate, rather than mitigate, potential disputes.

Reporters and headline writers who use words like “confusion” and “chaos” to draw clicks should think about the distrust they are sowing.

Or here’s another that’s a little more radical: Partisan leaders in Congress from both parties could preemptively agree on a power-sharing agreement between the two parties (rather than narrow majority rule) that would be triggered by a close and suspicious election, so it doesn’t create a fundamental crisis of government legitimacy. Frankly, this might be better for the country so that not everything hinges on a few thousand votes in a few swing states.

Perhaps the silver lining of Iowa is that it is a wake-up call reminding us we are not at all prepared for the very credible threats of electoral meddling, or even just basic technology failure. We still have an entire nine-month gestation period to get ready. Let’s not dawdle.

Related:

Democrats use the myth of a romanticized, whitewashed 'heartland' at their peril

Democrats should stop taking corporate PAC money to regain voter trust

America's tuning out impeachment because no one's made us care