Just two years of exercising, eating healthier food and doing a little brain training boosted people’s memory function, researchers reported Monday. It’s the first proof that some of the things people have been trying to prevent Alzheimer’s may actually work.

The study, done in Finland, doesn’t point to any one thing people can do to prevent memory loss. Instead, it’s a cocktail, the researchers told a meeting of Alzheimer’s experts.

“It’s the first time we have been able to give people a kind of recipe for what is useful,” said Maria Carrillo, vice president of Medical & Scientific Relations at the Alzheimer’s Association.

Sign up for top Health news direct to your inbox.

Various studies have given people hints at what can prevent Alzheimer’s. Some are common-sense: What keeps you healthy overall, such as regular exercise and eating plenty of fruits and vegetables, also helps prevent Alzheimer’s. Others have shown that people who are socially engaged are less likely to develop memory loss. Still others have shown that keeping the brain active with puzzles or games can help, and a whole industry has arisen out of that research.

Dr. Miia Kivipelto of the Karolinska Institutet in Sweden and the National Institute for Health and Welfare in Helsinki, Finland, and colleagues tested people with a combination of all these approaches. They randomly assigned half to do the entire batch of changes, and the other half simply got general health advice.

They tested all the 1,260 volunteers, aged 60 to 77, at the beginning of the study and then two years later.

Those who did exercise, changed their diet, made an effort to socialize and who did the memory training did significantly better on the memory tests two years later, Kivipelto told the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference in Copenhagen.

It’s the kind of study that researchers say is the most solid — one that randomly assigns people to a treatment or no treatment, and watches the changes in real-time, instead of relying on people to remember what they ate or whether they exercised.

“Doing all this stuff is good for your brain and good for your body.”

It’s similar to what Susan Megerman is trying for herself. Megerman, 69, doesn’t have any memory issues yet, and she does not want to have any if she can prevent it.

“I don’t feel panicked, but with cardiovascular disease in my family, I worry about what that can do,” Megerman told NBC News. She watched her father lose his short-term memory as he struggled with heart valve disease and clogged arteries before his death at age 82 in 1999.

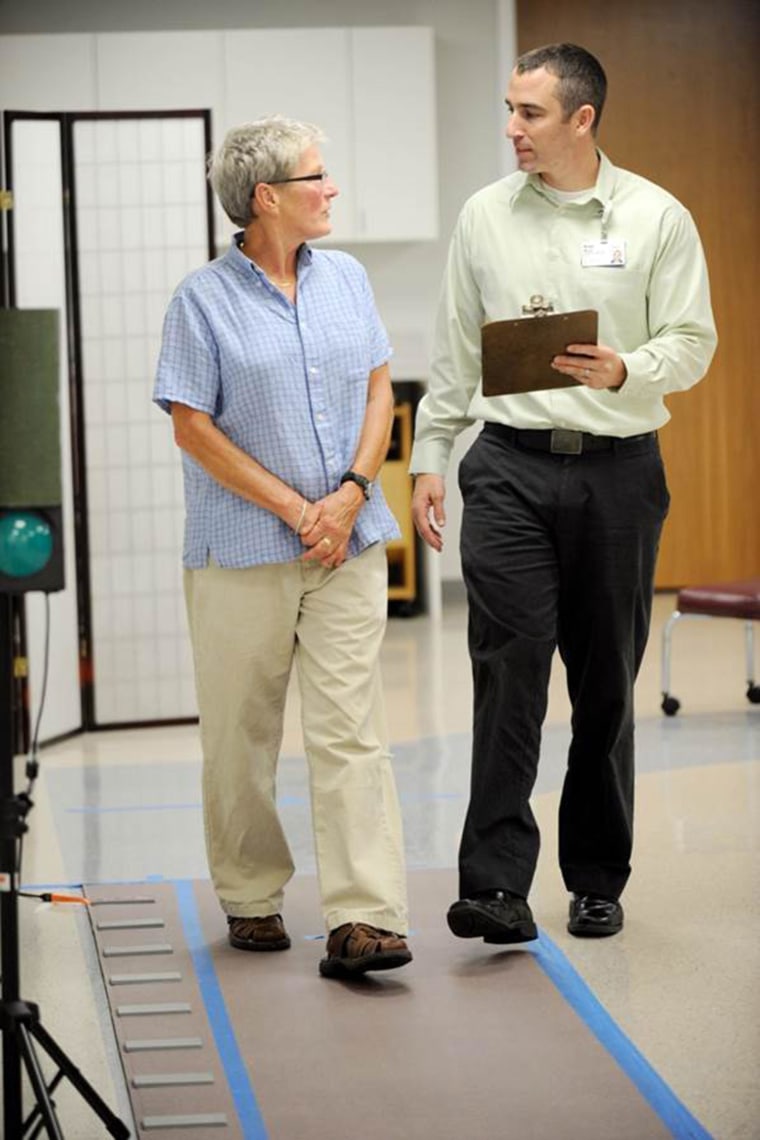

Megerman, a program coordinator at Boston’s Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, has tried to eat more healthily, exercise more and control her weight. She also takes part in the medical center’s Brain Fit Club, where participants can do computer-based brain training, meditation or tai chi.

Megerman went for an assessment. “I was finding myself having difficulty remembering words. Then there were times when I would forget things. So I got nervous,” she said.

Luckily, she doesn’t have any serious deficits. People forget stuff all the time. But Megerman didn’t want to just sit back and relax. For one thing, she had a cancer scare when she had an ovarian tumor removed when she was 56.

For another, she realizes she might live a long time and she doesn’t want to be impaired. “I recognize that I possibly have some longevity genes,” Megerman said. “If I have got those, I had better take advantage of them." Her great-grandfather lived to 100, she said, and her mother lived to 93 even though she had heart disease, also.

Plus, Megerman says she has a lot to live for. “My grandchildren are aged 4 and younger. When they are ready to marry I’ll be 90,” she said. “I want to stay independent and capable and available for them. I work in a wonderful place and I love what I am doing. I want to work as long as I feel I want to work.”

So Megerman has made some changes. “I work really hard not to eat junk food. I generally don’t keep ice cream in the house any more,” she said. “I eat a lot of fruits and vegetables. I try to eat as little processed carbohydrate as possible.”

The study has not yet shown that the "recipe" actually does prevent Alzheimer's. That'll take years more to demonstrate, says Dr. Ronald Petersen of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

"I think the takeaway message from this study is that we can do something for ourselves as we age," Peterson told NBC News.

"I think the takeaway message from this study is that we can do something for ourselves as we age."

"By our watching our own vascular risk factors, our blood sugar, our blood pressure, our weight, and engaging in active activities and engaging in cognitive activities that actually stimulate our mind, we might be able to actually reduce the risk of us developing Alzheimer's Disease in the future."

Experts project that the number of Americans living with Alzheimer’s will triple in the next 40 years, which means that 13.8 million will have the mind-robbing disease by 2050. It’s the sixth leading cause of death in the United States, directly implicated in more than 83,000 deaths each year.

A recent study suggests it may be involved in killing far more people, however — 500,000 people each year.

There’s no cure and treatments are very poor. Doctors hope that people can find better ways to prevent it, to blunt the effects of what will otherwise be a tsunami of disease. They're also looking at ways to test early for signs of Alzheimer's, in case it's easier to treat before people even develop symptoms.

“I’m doing what I need to do to stay healthy,” Megerman said. “Doing all this stuff is good for your brain and good for your body.”

NBC's Judy Silverman contributed to this story.