Tens of thousands of mental patients and troops unknowingly became malaria test subjects during the 1940s — part of a secret federal rush to cure a dread disease and win a world war, according to a book published Tuesday that exposes vast, previously unknown breaches of medical ethics.

“The Malaria Project” — operating via the same covert White House machinery that drove the Manhattan Project — tasked doctors with removing malaria from naturally exposed U.S. troops then injecting those strains into people with syphilis and schizophrenia, reports author Karen Masterson, who researched files at the National Archives.

Some details of the project have been previously reported, but the book's new revelations renew debate over the ethics of using unsuspecting people as test subjects — similar to the Tuskegee Syphilis Study on low-income black men.

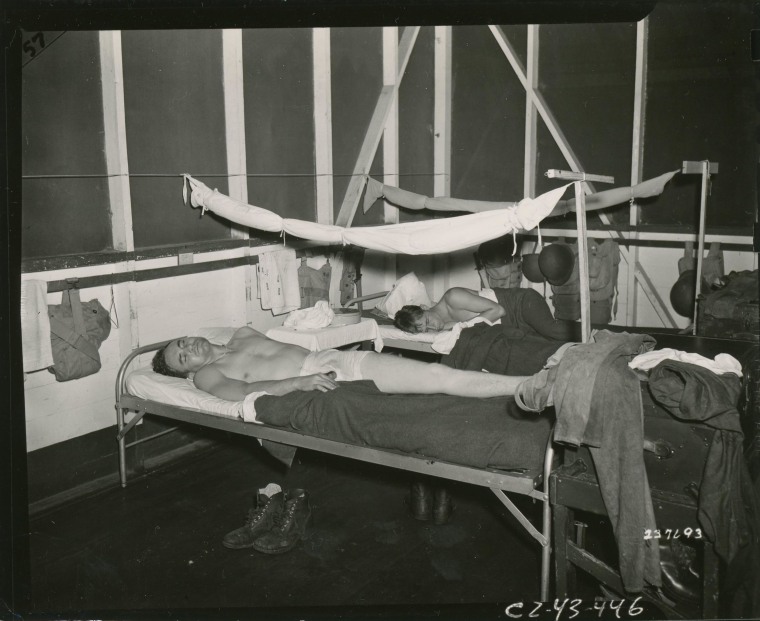

Thousands of mental patients at eight hospitals became “pod people,” made and kept ill so scientists could use their blood in clinical drug trials. Eventually, pockets of troops, many in the South Pacific, unwittingly became guinea pigs for potential anti-malaria drugs. But certain treatments were worthless or harmful, leaving numerous service members with lasting organ damage, said Masterson, whose book also is titled “The Malaria Project.”

“Some of the guys were ruined, sent home because they had so many malaria relapses. Their bodies were wrecked,” said Masterson, who teaches science writing at Johns Hopkins University. She did not document any malaria-test-related deaths among troops but estimates 10 percent of the infected hospital patients perished.

As she initially poured through the records, “I was appalled about how horrible our doctors were during the war, to be so loose with experimenting on people,” she said. But while reading urgently toned letters between the project’s doctors, Masterson began to “back way off my evil scientists first impression, and I got a little bit closer to the emergency situation then.”

Certainly, the moral violations are clear when viewed in a modern light. Yet a hard truth remains: American doctors were learning what worked, what didn’t after a centuries-long battle to cure malaria. Meanwhile, Nazi doctors, who had been conducting similar tests, were in possession of a promising new drug.

“In North Africa, the Allies captured this analogue. They get this magic formula, stealing it from the Germans,” Masterson said.

“It’s sent back to The Malaria Project and developed into a chloroquine,” a safe drug that, she added, “went on to save more lives than any other drug in history.”

Carried by infected mosquitos, malaria had been an insidious scourge for U.S. troops during World War II in the Pacific and Mediterranean theaters. About a half million troops contracted the disease, giving U.S. scientists extra incentive to uncover a cure.

“This project brought us out of the dark ages on malaria,” Masterson said. “We knew so little about malaria as a parasite because you couldn’t grow it in cultures. You needed infected people.”

But with so much of today’s malaria knowledge rooted in those coerced human experiments, can scientists use that wisdom in clear conscience? To be sure: Malaria remains a big killer — claiming 627,000 lives in 2012, according to the World Health Organization.

“There’s a long list, many instances, sadly, tragically, where immoral experiments generated life-saving knowledge,” said Arthur Caplan, founding head of the division of bioethics at NYU Langone Medical Center and a frequent NBC News contributor.

In the late 1940s, U.S. government researchers intentionally infused gonorrhea and syphilis into hundreds of Guatemalans, including institutionalized mental patients, and did so without their permission to develop new prevention methods.

More infamously, there was the Tuskegee Syphilis Study in which the government charted for decades the effects of the untreated disease on mostly poor and uneducated black men. The experiment ended in 1972 amid widespread condemnation.

Prior to Masterson’s book, some threads were known about the American malaria experiments — but not the full scope, said Caplan, who believes the attained malaria knowledge must nonetheless continue to be used.

He offers three caveats to modern medical researchers who are considering tapping unethical studies of the past to help treat ill people in the present.

“One, don’t give credit to the original authors; you don’t want people to get glorified for doing immoral, unethical things,” Caplan said. “Two, give your rationale for using the data. We still use the Tuskegee study today because it's the only information we have about end-stage syphilis. Three, you have to have high stakes — life-saving work.”

“There are no easy answers,” agreed I. Glenn Cohen, a Harvard Law School professor specializing in medical ethics.

"But in trying to reach an answer on a particular case, here is how I look at it: avoid hindsight bias; determine whether the study violated contemporaneous research ethics rules not whether it offends our current understandings," Cohen said. "In this case, it likely violated even contemporaneous rules."

Further, researchers should pinpoint whether an original study’s shady morals also made it scientifically invalid, Cohen added.

“If the data is bad, it is easy to throw it away,” Cohen said. “That does not appear to be the case here …”

“In the case of the anti-malarials … these are drugs that have been approved and are in wide circulation,” Cohen said. “Would we even be able to take them off the market?”