When you're recounting the drama of cosmic origins, the show must go on — even if you're a quadriplegic recovering from a medical crisis.

At least that was the theatrical rule that world-famous physicist Stephen Hawking followed this week, in the wake of a medical episode that kept him and his entourage from traveling to Seattle for a sold-out lecture on the origins of the universe.

Wednesday's appearance at the Paramount Theatre — presented by the Oregon-based Institute for Science, Engineering and Public Policy, or ISEPP — was the last of three scheduled stops on the Cambridge professor's U.S. lecture tour. Hawking, who suffers from a progressive neurodegenerative disease that has almost completely paralyzed him, was due to travel to Seattle from San Francisco. But when he was taken off his respirator Monday morning, "he basically flat-lined," said Terry Bristol, ISEPP's president and executive director.

"They had to resuscitate, and that panicked a few people," Bristol told the audience. "But he's been there before."

Once the crisis had passed, Hawking wanted to go ahead with the Seattle leg of the trip, but his medical caretakers — including his wife, Elaine — thought he should stay put awhile longer, Bristol said. So Hawking and his aides worked with Intel, ISEPP and the Paramount to set up a Web-based teleconferencing link from a Bay Area hotel.

At the appointed time, after a couple of minutes of video-display fiddling, Hawking's image flashed onto the large screen set up over the Paramount's stage — setting off a round of applause. Then the physicist dove right into a split-screen multimedia presentation that traced the development of theories on cosmic origins, beginning with African creation myths.

Beginning of time

Was the universe eternal, or did it have a beginning? A key turning point came in the 1920s, when astronomer Edwin Hubble observed other galaxies and concluded that the universe was expanding. Hawking said Hubble's finding was "one of the most important intellectual discoveries of the 20th century, or any century."

That cleared the way for the current view that the universe began with a Big Bang — but it didn't clear up the scientific controversy.

"Many scientists were still unhappy with the universe having a beginning, because it seemed to imply that physics broke down," Hawking said. "One would have to invoke an outside agency, which for convenience one can call God, to determine how the universe began."

Hawking traced how scientists have tried to address that conundrum using quantum theory, inflationary Big Bang theory and observations of the cosmic microwave background radiation — sometimes known as the Big Bang's "afterglow."

He sketched out a view in which "time can behave like another direction in space under extreme conditions." As an example, he used the oft-cited example of reaching the South Pole, then trying to point even further south. In the same way, the beginning of the universe followed the same laws of physics that applied to every other point in space-time, but it would not be possible to point to a time before the Big Bang, he argued.

"The beginning of the universe would be covered by science," he said.

Later, he said that science was making inroads on questions that had once been exclusively the province of religion.

"The one remaining area that religion can now lay claim to is the origin of the universe," Hawking said, "but even here, science is making progress and should soon provide a definitive answer to how the universe began."

Ability despite disability

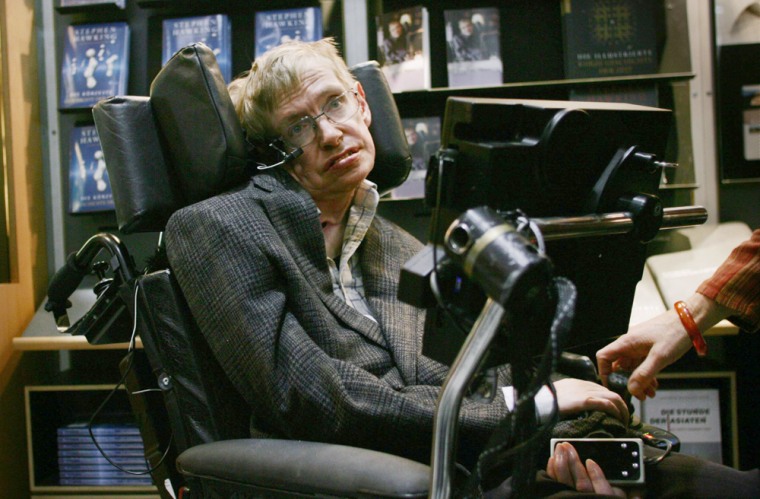

Part of Hawking's appeal has to do with his sheer ability to carry on despite his disability. The substance of the talk wasn't new to readers of popular books on cosmology — including Hawking's own updated classic, "A Briefer History of Time" — and many in the audience likely came more to get a glimpse of the man in person. For that reason, the event's organizers did offer ticket refunds.

Nowadays, the physicist controls his computerized voice system using a blink-activated infrared system embedded in his eyeglasses. To set off each section of his prepared text, he blinks an eye, slightly scrunching up his cheek in the process. He can employ the same system to compose answers on the fly — although Wednesday's presentation was completely prepared in advance.

Despite the teleconferenced video and the flat tone of Hawking's synthesized computer voice, his outspokenness and humor shone through as lively as ever. The highlight was a recap of Hawking's favorite answers to frequently asked questions — some of which drew so much applause from the Seattle crowd that Bristol, the master of ceremonies, occasionally had to repeat the answers. Some examples:

- What did he think of "The Simpsons" TV show, which has had Hawking as an animated guest star? "It's the best thing on American TV."

- What was his view of the Bush administration's limits on human embryonic stem-cell research: "America will be left behind if it doesn't change policy."

- What did he think of the program to send American astronauts back to the moon? "Stupid," he answered. "Sending politicians would be much cheaper, because you don't have to bring them back."

- How high is Hawking's IQ? The physicist replied that he didn't know. "People who boast about their IQ are losers," he said.

- Which late personage would he rather meet, Isaac Newton or Marilyn Monroe? "Marilyn," Hawking said. "Newton seems to have been an unpleasant character."