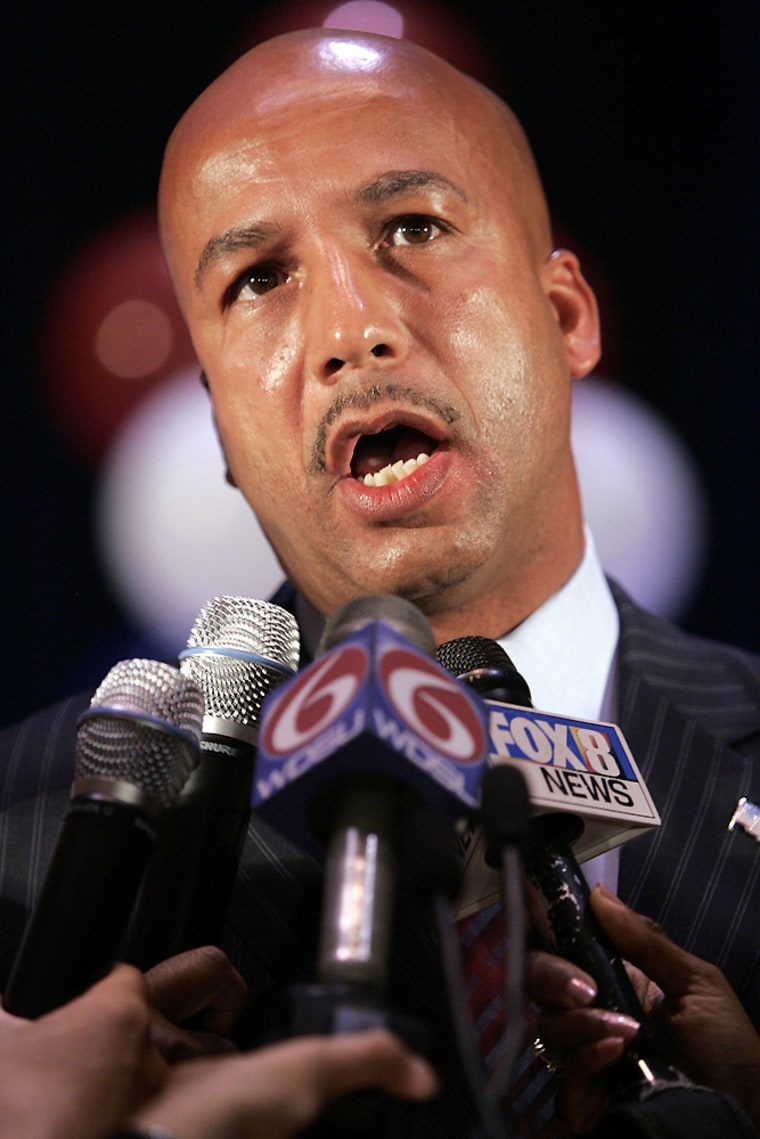

In a complete reversal of support from four years ago, Mayor Ray Nagin scored heavily with black voters and was practically abandoned by whites as he and Lt. Gov. Mitch Landrieu won spots in a mayoral runoff election.

The black incumbent, who received most of his support from white voters in the 2002 election, garnered less than 10 percent of the vote Saturday in predominantly white precincts, according to GCR & Associates Inc., a consulting firm analyzing demographic data for the New Orleans Redevelopment Authority.

But Nagin, who offended many white voters in January when he suggested God wanted New Orleans to remain a “chocolate city,” saw black voters rush to his defense. He received 65 percent or more of the vote in predominantly black neighborhoods, the consultant found.

Landrieu, who is white, finished with 29 percent of the overall vote to Nagin’s 38 percent. He finished second in black neighborhoods to Nagin and second in white neighborhoods to third-place finisher Ron Forman, bolstering his claims that he can help bring together diverse groups to help New Orleans emerge from the devastation left by Hurricane Katrina.

Landrieu said Sunday that the number of voters who chose candidates other than Nagin demonstrated that voters want change. “This city, this great city, calls for change,” he said.

Nagin, a former cable television executive seeking his second term as mayor, said his overall win is an endorsement of his performance and his plans for the city’s future.

“I just feel we’re on the right track, and people have verified that to me,” he said.

Runoff May 20

The numbers suggest it will be a serious challenge for Nagin to broaden his support in time for the May 20 runoff.

“His one shot is to get enough of the whites who liked him four years ago to like him again,” said political analyst Elliott Stonecipher.

Those votes are all the more important because the city is whiter than it was before Katrina hit Aug. 29: Fewer than half the city’s 455,000 residents have returned, most of those displaced are black. Only about 20,000 evacuees participated in Saturday’s election by absentee ballot, fax and satellite stations, although an unknown number returned to the city to vote in person.

Nearly half of voters in predominantly white areas turned out, compared with about 30 percent of registered voters in black neighborhoods, which also tended to be the worst hit by flooding.

One-third of voters participate

About 36 percent of the city’s 297,000 eligible voters participated in Saturday’s election, some traveling hundreds of miles to help decide who will lead one of the biggest urban reconstruction projects in U.S. history.

Nagin and Landrieu led a field of 22 candidates, which included a wide range of other choices, including business leaders, a lawyer and a minister. Yet voters, as they did in several other municipal races Saturday, chose two men already in the political spotlight.

The large number of displaced residents made the election a tricky experiment in democracy. Campaigning went nationwide and civil rights activists questioned whether the balloting could be fair.

Voter turnout was significantly lower than the 46 percent who took part in the 2002 municipal primary, but it was such an unusual election that political observers said it was difficult to characterize whether turnout was better or worse than expected.

Incumbents hold their own

Some, however, were surprised that incumbents fared well almost across the board, winning their elections outright or qualifying for runoffs after months of speculation that anger over the city’s handling of the hurricane would cost some their jobs.

“It was normal, natural to expect some such expression” of frustration against current officeholders after Hurricane Katrina, Stonecipher said. “Instead, we got the opposite.”

Nagin lost support under criticism of his post-Katrina leadership and some of his off-the-cuff remarks. Business leaders, who supported him in his 2002 run, largely lined up behind Forman, chief executive of the Audubon Nature Institute, and other trailing candidates.

Forman, who captured 17 percent of the vote, had not endorsed anyone by Sunday. Many conservatives dislike the Landrieu family, so neither candidate in the run-off was likely to win over all the Forman voters, political observers said.

Landrieu has held office in Louisiana for nearly two decades and is the brother of Sen. Mary Landrieu. His father, Moon Landrieu, was the last white mayor of New Orleans in the 1970s but is well-liked in the black community for his decision to open high-ranking jobs to black professionals at City Hall.

Analyzing the turnout

No major problems were reported at polling places, but the Rev. Jesse Jackson said Sunday the low overall turnout should be a mandate to do more to encourage participation among voters unable to return since Katrina turned neighborhoods into debris fields.

Jackson said the election will be challenged in court; he and other critics have said the city should have set up out-of-state satellite polling stations, in evacuee hubs such as Houston and Atlanta, to encourage voter turnout.

Stonecipher, however, said the turnout may not be a sign of disenfranchisement as much as an indication that many registered voters don’t plan to return to New Orleans.

“The turnout really does speak to the issue of which and how many New Orleanians are still New Orleanians,” he said.