Just a few steps inside the front door, an autographed Lance Armstrong poster greets visitors to Colorado Altitude Training.

The cyclist is strategically perched — for peddling, as well as pedaling. His image offers a daily testament to the bond between a sports titan and a tiny company that suddenly finds itself immersed in a global anti-doping flap.

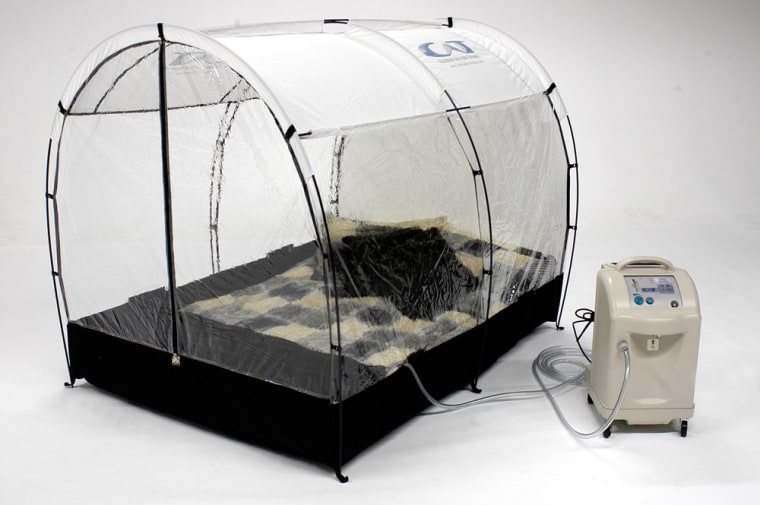

Armstrong, the seven-time Tour de France champion, once collaborated with Colorado Altitude Training to design a portable, low-oxygen chamber that helped boost his red blood cell count, his endurance and his win total. Armstrong's success inspired five of the top six finishers at this year's Tour to snooze in CAT-made tents. Even Armstrong’s former girlfriend Sheryl Crow owns a CAT canopy that fits over her bed.

But as CAT founder and chief executive Larry Kutt walks past the poster, he wonders aloud whether the alliance with Armstrong might have sucked his company — and its products — into the sights of the World Anti-Doping Agency. After all, Armstrong and doping agency chief Dick Pound have spent years publicly sniping at each other, with Pound hinting that Armstrong is a drug cheat and Armstrong lobbying for Pound to be bounced from his post.

“We’ve had nothing but good vibes all the way around until WADA brought this up,” Kutt says. “We’re not 100 percent clear on (the) motive.”

Now, Kutt and his 14 employees work in the shadow of a potential sports ban. Last month, Pound and the anti-doping agency held off on banning the use of hypoxic chambers, but asked that studies look further into health implications.

"It doesn't mean we approve it," Pound said. But the agency refrained from adding the practice on the banned list — for now.

WADA has spent months looking at low-oxygen tents and other “hypoxic” gadgets that mimic the rare air found naturally at 12,000 to 14,000 feet above sea level. The Montreal-based watchdog on drugs in sport already has confirmed that athletes who train and sleep in hypoxic chambers do gain a bump in aerobic performance, something long suspected by elite athletes. For example, the U.S. long-track speedskating team paid CAT $155,000 to build six “mountain rooms” at its Milwaukee training base, then dominated in Torino by snaring seven Olympic medals.

Then last May, a WADA ethics panel ruled the technology violates the spirit of sport by “requiring no investment of skill or effort beyond entering a room or tent, donning a mask and flipping a switch.” In a past interview, Pound added: “If you live in the mountains, it happens naturally. If you live at sea level, it doesn’t. I mean, it’s pretty easy. … There will be people who can rationalize practically anything.”

While Kutt questions Pound’s deeper motives, a WADA spokesman says the agency is merely doing its job.

“If we go back to the origin, WADA was asked by its stakeholders to lead the process for stakeholder consideration of hypoxic chambers,” says Frédéric Donzé, manger of media relations.

“The prohibited list is reviewed on an annual basis,” Donzé adds, and this scrutiny is part of that task. “WADA has played the role of facilitator for the discussion.”

Standing in a starkly lighted rear room filled with his products, Kutt smirks when he hears Donzé’s comments.

“Facilitator,” he says with a laugh. Kutt has offered to set up his clear-plastic tents at WADA headquarters to show Pound and his staff exactly how they work. He received no reply, he says.

Before the company was founded in 1997, Kutt’s engineers studied every bolt, knob and hose to make sure the units were “100 percent safe."

"We now have 10 million hours of athlete use without untoward effects — you couldn’t give 10 million doses of Tylenol without some untoward effects," he said. But WADA has cast doubt on that too, saying research of the technology revealed “some discrete signs, such as sleep disorders, immunological and metabolic disorders.”

One of those researchers, University of Paris physiology professor Jean-Paul Richalet, has since accused WADA of misquoting his study.

“It appears WADA intentionally misrepresented the facts … in order to influence the opinions of its stakeholders against altitude simulation,” Kutt says. “This is a good example of the kind of thing that we have been up against with WADA.”

So from the small CAT office, with a one-room shipping department and its short row of desk cubicles, Kutt and his employees wage a quiet war. CAT calls itself the market share leader in the altitude chamber industry, boasting of clients who won world titles in almost every endurance sport.

The company is privately held and, consequently, said it would not release its revenue figures. Two of CAT’s competitors include Hypoxico, based in New York City, and GO2Altitude, which is headquartered in Australia.

In recent years, Kutt also has opened lucrative new markets with the U.S. military and thoroughbred racing owners. But sports remain the soul of the company. Its location near a green foothills prairie allows employees to hop on their bikes at lunch.

“There’s maybe one person in our company who doesn’t ride a bike at some level,” says CAT marketing manger Rip Young.

Its Web site is packed with endorsements from more than 50 amateur and pro athletes and teams, including American cyclist Levi Leipheimer, who finished 13th in this year’s Tour de France. At his Santa Rosa, Calif., house, he set up a CAT tent big enough to accommodate himself, his wife and their three dogs each night. He also takes a smaller tent to Europe when he competes there.

By sleeping in the low-oxygen tents, Leipheimer says he has gained speed on his bike. He said it is almost like he is training in his sleep.

“I’m always having good days,” he says. “I think it has raised my metabolism."

But if WADA prohibits the use of this technology, Leipheimer says he will be forced to snuff that endorsement along with any use of the products. If that happens, the cyclist says he might resume training in mountain towns — or even move to one. But he jokes that WADA may frown on that, too.

“I don’t know, maybe they will ban us from actually going to altitude,” Leipheimer says.

In an odd way, the potential crackdown has presented CAT with a small sales opportunity by offering strong evidence that the tents could work wonders for weekend athletes, say both Kutt and Young. Tents start at $4,995, with full-room, in-home conversions available for $14,500 and up.

“You could say this has given more credibility to the benefits of our products,” Young says. “It kind of reinforces that fact that altitude training actually does something. But I wouldn’t say overall it’s going to be a good opportunity. We want to see this remain ethical and legal in the eyes of WADA.”

Kutt, an entrepreneur with several startups on his resume, founded CAT in part because he believes drugs must be swept from sports. Artificial altitude, he says, is a safe and legal way to reap some of the boosts provided by illegal doping.

“Caffeine is a known performance enhancer, a pharmacological stimulant. But it’s legal in the WADA code,” Kutt says. “Well, I don’t drink coffee. I don’t drink alcohol either. But I do sleep in an altitude tent.”