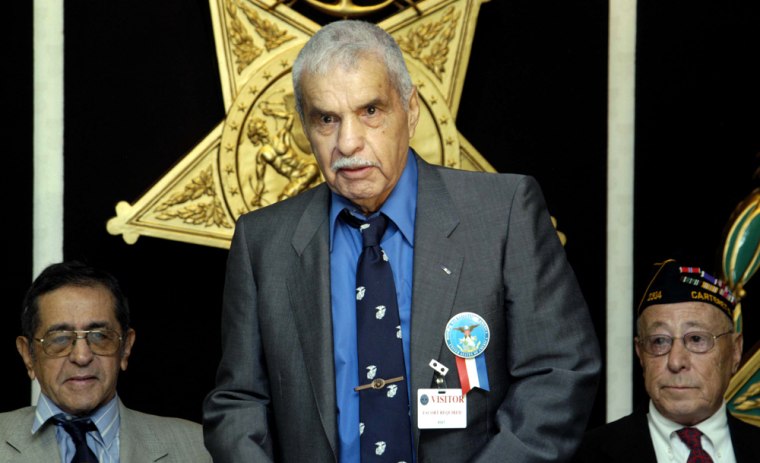

Guy Gabaldon, who as an 18-year-old Marine private single-handedly convinced more than 1,000 Japanese soldiers to surrender in the World War II battle for Saipan, died Thursday at his home in Old Town, Fla. He was 80.

The cause was a heart attack, his son Tech. Sgt. Jeffrey Hunter Gabaldon said Monday.

Using an elementary knowledge of Japanese, bribes of cigarettes and candy, and trickery with tales of encampments surrounded by American troops, Gabaldon was able to persuade soldiers to abandon their posts and surrender. The scheme was so brazen — and so amazingly successful — it won the young soldier the Marines' highest honor, the Navy Cross, and fame when his story was told on television's "This Is Your Life" and the 1960 movie "Hell to Eternity."

"My plan, as impossible as it seemed, was to get near a Japanese emplacement, bunker, or cave, and tell them that I had a bunch of Marines with me and we were ready to kill them if they did not surrender," he wrote in "Saipan: Suicide Island," his 1990 memoir. "I promised that they would be treated with dignity and that we would make sure that they were taken back to Japan after the war."

Gabaldon's small stature (he was less than 5 foot 4 and about 130 pounds) and the piecemeal Japanese he picked up from a childhood friend helped him earn the trust of the enemy, who believed his story of hundreds of looming troops. In a single day in July 1944, Gabaldon was said to have gotten about 800 Japanese soldiers to follow him back to the American camp.

Pied Piper of Saipan

His exploits earned him the nickname the Pied Piper of Saipan.

The private acknowledged his plan was foolish and, had it not been pulled off, could have resulted in a court-martial. His family suspected his initial disobedience — though they say officers later approved — might have kept him from receiving the Medal of Honor.

"My actions prove that God takes care of idiots," he wrote.

Born March 22, 1926, in Los Angeles, Gabaldon signed up for the service on his 17th birthday and arrived on Saipan on D-Day. His military career was cut short after two-and-a-half years by injuries from machine gun fire. He spent the years that followed running a variety of businesses, including a furniture store, a fishing operation and an import-export firm, and the unsuccessful pursuit of a California congressional seat in 1964.

Services for Gabaldon were to be held Tuesday in Cross City, Fla., where a Marine color guard was to fire a 21-gun salute and present his wife, Ohana Suzuki, with a flag. His remains are to be scattered on Mount Tapochau on Saipan and in the U.S.

Addicted to taking prisoners

Besides Jeffrey Hunter Gabaldon of San Diego, he had 10 other children, eight of whom are still living: Guy Jr., and Manya, both of Orlando, Fla.; Russell, of Lake Havasu, Ariz.; Antonio and Yoshio, both of Saipan; Raymond, of Las Vegas; Hanako Cruz, of Modesto, Calif.; and Aiko, of Old Town. He is also survived by 17 grandchildren and one great-grandchild. His first marriage, to the late June Tikunoff, ended in divorce.

In "Suicide Island," Gabaldon said capturing the Japanese amounted to more than just a badge of honor for him.

"When I began taking prisoners it became an addiction. I found that I couldn't stop. I was hooked," he wrote. "It became a way of life."