Astronomers might have seen the very first stars in the universe. If so, these are incredible stars, some 1,000 times as massive as the sun.

The alternative is just as interesting: The objects might be early black holes consuming gas voraciously and spitting out radiation like crazy as nascent galaxies form.

The observations, by NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope, were first reported on a preliminary basis in November 2005 in the journal Nature. A new analysis was announced Monday.

"We are pushing our telescopes to the limit and are tantalizingly close to getting a clear picture of the very first collections of objects," said Alexander Kashlinsky of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, lead author of two reports to be published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters. "Whatever these objects are, they are intrinsically incredibly bright and very different from anything in existence today."

Wayback machine

The light comes from objects that are more than 13 billion light-years away. That means the light began its journey more than 13 billion years ago. The universe is just a smidgeon older, at 13.7 billion years, and astronomers are pretty sure it took a few hundred million years for the matter of the big bang to spread out enough, and cool, to allow the first stars to form.

A little math therefore shows that these newfound objects are indeed the infants of the universe. But what are they? If they are stars, they are about 10 times more massive than theories suggest the first stars would have been.

The mysterious objects are in clusters. If they are each stars, then the clusters might be the first mini-galaxies. And if so, each apparently has a mass that's less than a million suns. Our Milky Way, by contrast, holds the mass of about 100 billion suns and is thought to have been built up by mergers of smaller galaxies — perhaps like those the astronomers now think they might be seeing.

What they see

When light travels to us from near the beginning of the universe, it is stretched. Other observations of the universe's first light have been made in the microwave range. This cosmic microwave background reveals patterns of matter clumping, but no specific objects.

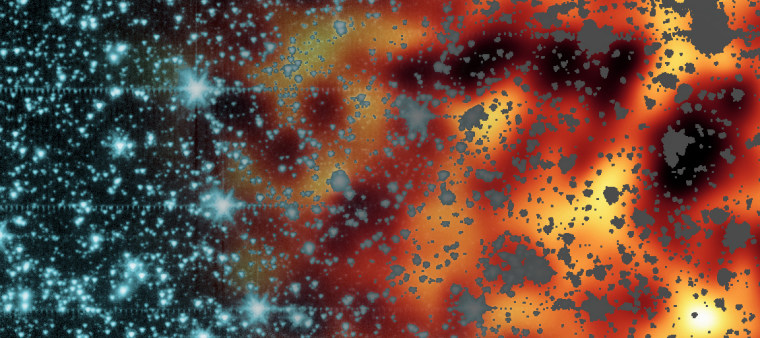

The light measured in the new study is thought to have started as ultraviolet and optical light, and it has been stretched over time to infrared. Kashlinsky's team calls it the cosmic infrared background and describes it as a diffuse light from the early time when structure first emerged.

"There's ongoing debate about what the first objects were and how galaxies formed," said Harvey Moseley of Goddard, a co-author of the new papers.

Some think our galaxy and other large galaxies grew through mergers. One recent study questioned that notion, however.

"We are on the right track to figuring this out," Moseley said. "We've now reached the hilltop and are looking down on the village below, trying to make sense of what's going on."

Difficult observations

The problem in making sense of it all lies with the fact that the observations are not clear-cut. The scientists had to remove light from foreground stars and galaxies, and then study fluctuations in what is a relatively diffuse light.

"Imagine trying to see fireworks at night from across a crowded city," Kashlinsky suggested. "If you could turn off the city lights, you might get a glimpse at the fireworks. We have shut down the lights of the universe to see the outlines of its first fireworks."

The researchers expect NASA's planned James Webb Space Telescope will be able to identify the nature of the newfound clusters.