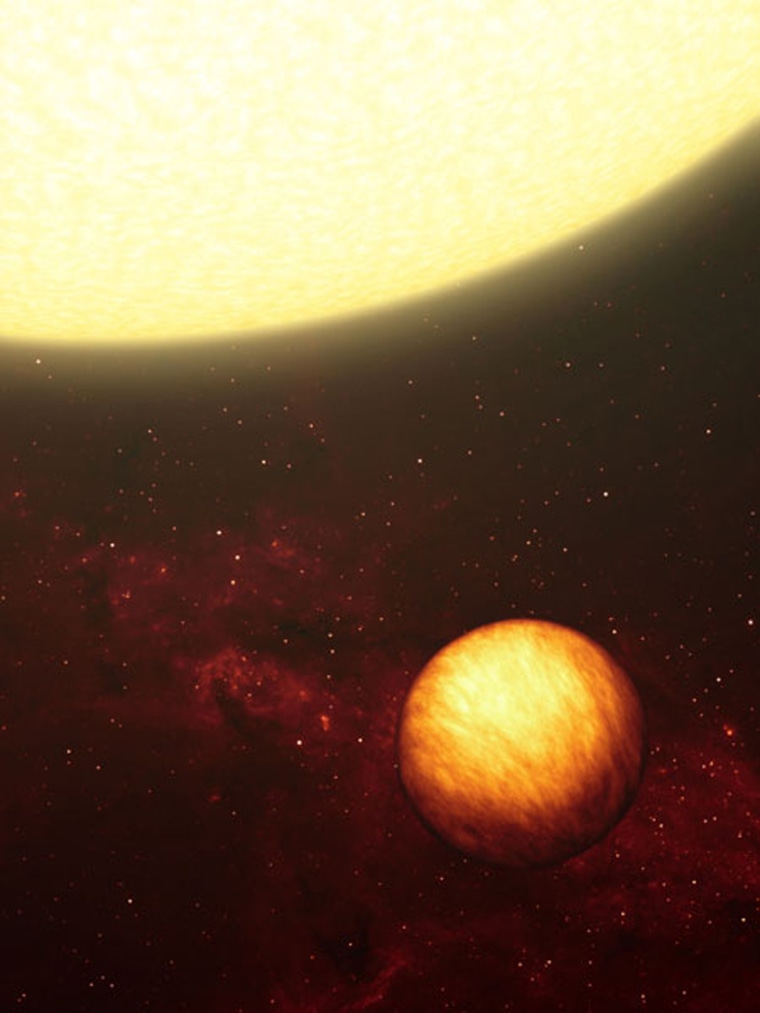

Heated winds on at least three planets outside our solar system blow so strongly that the worlds are kept at a constant toasty temperature, even the night sides that never face their parent stars.

The planets are called "hot Jupiters" because they are large and gaseous like Jupiter, but orbit much closer to their stars. All three orbit within about five million miles (eight million kilometers) of their stars, much closer than Mercury is to our sun. Scientists think winds on the planets blow at supersonic speeds, as strong as 9,000 miles (14,500 kilometers) per hour, churning their home worlds’ atmospheres and keeping temperatures on their dark sides from plunging.

For more than a decade scientists have wondered whether, like Jupiter, the temperature on hot Jupiters are constant, or if there are sharp temperature differences between their day and night sides.

The findings

Last October, a team of astronomers led by Brad Hansen of the University of California, Los Angeles discovered evidence of the latter on a nearby hot Jupiter called Upsilon Andromeda b.

Hansen's team found that one half of Upsilon Andromeda b was as hot as molten lava, while the other half was chilled possibly below freezing. The researchers speculated that the sunlit side of the fire and ice planet was perhaps tidally locked to its stellar parent, like the moon is with Earth, so that only one side of the planet faced the star. Another possibility was that Upsilon Andromeda b was somehow shedding heat from its star rapidly into space, before its winds could circulate it to the night side.

The new finding, presented here at the 209th meeting of the American Astronomical Society, suggests the alternative heating scenario predicted by scientists can occur as well.

In late 2005, the researchers used NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope to gather infrared readings from each of the planets at eight different positions in their orbits. They measured the thermal brightness of the planets when their day sides faced Earth, when their night sides faced Earth and at various phases in between. They found no variation in the infrared brightness, suggesting no widely varying temperature differences between the planets' day and night sides.

Instead, the planets all appeared to have a uniform temperature of about 1,700 degrees Fahrenheit (925 degrees Celsius). The planets are all slightly cooler than they would be if they did not have winds to circulate heat.

Slideshow 12 photos

Month in Space: January 2014

"The cooling occurs via thermal infrared radiation, which is why the planet has a more uniform brightness," said study team member Eric Agol of the University of Washington. "The heat absorbed on the dayside is carried by fast winds, partly releasing the heat on the day side and partly on the night side."

The three planets are 51 Pegasi, HD179949b and HD209458b. They are located about 50, 100 and 147 light-years away from Earth, respectively. Because they each orbit so close to their stars, the researchers think the planets are probably tidally locked to their stellar parents.

51 Pegasi was the first planet discovered orbiting another star in 1995. Since then, the number of known extrasolar planets has swollen to more than 200 and the majority of them are hot Jupiters. Astronomers expect to eventually find large numbers of smaller planets, when technology allows.

More to learn

Whether the majority of hot Jupiters are evenly heated or experience sharp temperature contrasts remains unclear.

"Variations in their atmospheric chemical composition or dust content could change how fast they absorb and reradiate heat, and thus whether the winds can carry heat to the night sides," Agol told Space.com.

Agol cautions that both his findings and those of Hansen's team require further follow-up. In both cases the statistical significance of the findings is low, he said in an email interview. "With better data we will learn whether there really is a puzzle."

Knowing how hot Jupiters are heated could have implications for the search for extraterrestrial life.

"There has been some speculation that life might be able to exist on the cooler night-side of hot extrasolar rocky planets, but if those planets had similar weather patterns in their atmospheres as these hot Jupiters, that may not be the case," Agol said.