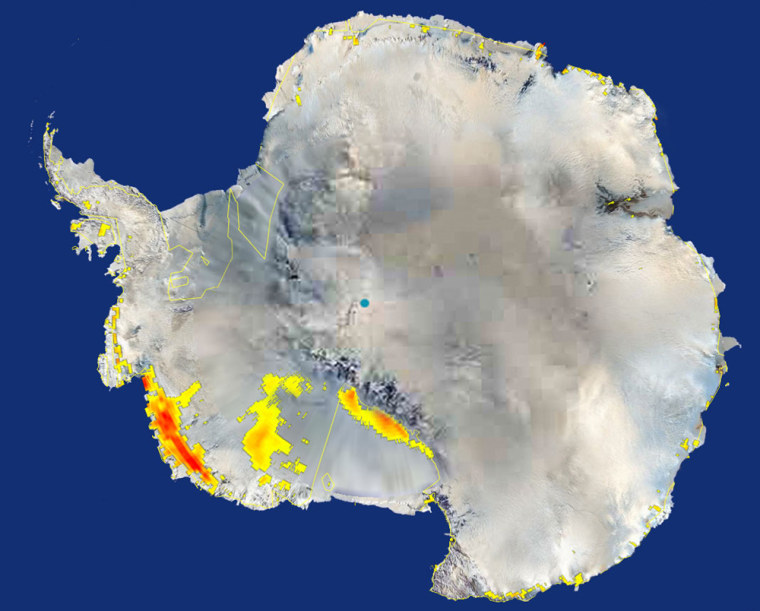

Extensive areas of snow melted in west Antarctica in January 2005 in response to warm temperatures, researchers reported in a new study, describing the melt as "the most significant" ever observed in the 30 years satellites have been used to track such changes.

The affected areas encompass a combined area as big as California.

"Antarctica has shown little to no warming in the recent past with the exception of the Antarctic Peninsula, but now large regions are showing the first signs of the impacts of warming as interpreted by this satellite analysis," study co-leader Konrad Steffen said in a statement.

"Increases in snowmelt, such as this in 2005, definitely could have an impact on larger scale melting of Antarctica's ice sheets if they were severe or sustained over time," added Steffen, director of the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

About 90 percent of the world's fresh water is locked in the thick ice sheets that cover west and east Antarctica. If just the smaller west sheet melts, scientists estimate it could cause a 15-foot rise in world sea levels. Even a three-foot sea level rise could cause havoc in coastal and low-lying areas around the globe, according to a recent World Bank study.

The team used a NASA satellite to measure snowfall accumulation and melt in Antarctica and Greenland from July 1999 through July 2005. The satellite sent radar pulses to the ice, measuring the echoed pulses that bounce back. That data was compared over time to detect changes. Ground station measurements validated the satellite results.

Odd areas of melt

In a statement, NASA said that the melt was widespread, "including far inland, at high latitudes and at high elevations, where melt had been considered unlikely. Evidence of melting was found up to 560 miles inland from the open ocean, farther than 85 degrees south (about 310 miles from the South Pole) and higher than 6,600 feet above sea level."

The areas included a vast stretch of the Ross Ice Shelf abutting the Transantarctic Mountain range. That shelf is the size of Texas and would lead to major glacier flows into the ocean were it to collapse.

That melt area is right at the border between the ice shelf and the mountain, it's kind of like a hinge," study co-leader Son Nghiem of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., told msnbc.com. "If that hinge is weakened it might have a dynamic effect on the ice shelf. It's still a hypothesis, but it's something we have to look into."

Referring to the overall melting, NASA added that "maximum air temperatures at the time of the melting were unusually high, reaching more than 41 F in one of the affected areas. They remained above melting for approximately a week" in January, which is the height of the Southern Hemisphere's summer.

The 2005 melt was not long enough for the melt water to flow into the ocean but it did create an extensive ice layer when water refroze after the melt. And some of that melt water is thought too have made its way through ice cracks, possibly affecting how ice sheets move.

"Water from melted snow can penetrate into ice sheets through cracks and narrow, tubular glacial shafts called moulins," Steffen said. "If sufficient melt water is available, it may reach the bottom of the ice sheet. This water can lubricate the underside of the ice sheet at the bedrock, causing the ice mass to move toward the ocean faster, increasing sea level."

Call for more studies

While no further melting had been detected through March 2007, the researchers said it could well happen again.

"It is vital we continue monitoring this region to determine if a long-term trend may be developing," Nghiem said. "We need to know what's coming in and going out of the ice sheets."

The peer-reviewed study, "Snow accumulation and snowmelt monitoring in Greenland and Antarctica," appears in the just published book "Dynamic Planet."