It took less time for Christopher Columbus to drum up the money and set sail for the New World than it has for the Columbus space lab to get off the ground.

This week, after 25 years in the making, Europe's treasured space laboratory will be launched on a flight to the international space station.

Scientists and engineers throughout Europe have been waiting for this moment since development of the $2 billion lab began in 1982. The lab is set to go up Thursday with a crew of seven aboard space shuttle Atlantis.

"Certainly, the scientists were on our case. They had experiments ready to go and they want science," said Daniele Laurini, a European Space Agency engineer who is helping to coordinate the project at Johnson Space Center in Houston.

"We're trying to accommodate that, making sure that we provide them science as soon as we hit the power button on the module," he said.

The 17-nation European Space Agency — ESA for short — signed up for NASA's space station project with the intent of launching Columbus in 1992 to celebrate the 500th anniversary of Christopher's famed sailing.

But NASA got bogged down, and the first piece of the space station wasn't launched until 1998. It was also slow going by partner Russia, and the first crew did not take up residence until 2000. Construction ceased in orbit when Columbia was destroyed during re-entry in 2003, and did not resume until 2005. Continued foam loss problems with NASA's shuttle fuel tanks further stalled things.

Once last month's space station mission ended successfully, and the shuttle Discovery was home safe, NASA managers were bombarded with congratulatory messages from European colleagues eager to get their own mission under way.

It's a matter of pride as much as scientific prowess, said astronaut Hans Schlegel, a German physicist who will accompany Columbus into orbit.

Until now, Schlegel noted, Europe has contributed a scientific space instrument or experiment here and there.

"But all of a sudden, we are a major player. We are a major contributor," he said. "It's really the beginning of a new time frame for Europe in human spaceflight."

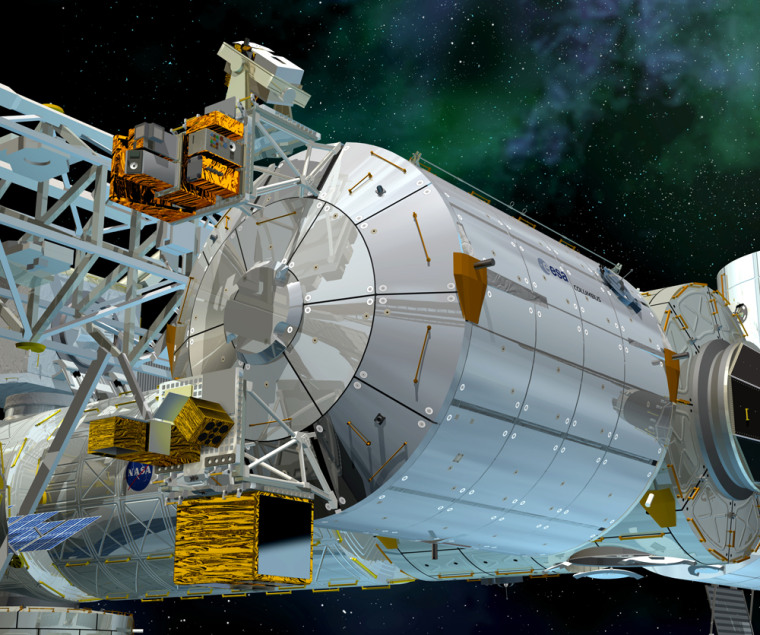

The Columbus lab — a 23-foot-long cylinder — will become the eighth room added to the international space station, but only the second laboratory. Destiny, NASA's larger lab, was carried to the space station by Atlantis in 2001.

The biggest and most elaborate lab of all — the Japanese Space Agency's Kibo, which means Hope — will require three shuttle flights to get everything up, starting in February.

A French Air Force general, Leopold Eyharts, will fly on Atlantis and remain on the space station for more than two months, working to get Columbus up and running. Schlegel, meanwhile, will take part in two spacewalks to help install Columbus.

Atlantis' five other astronauts are American, and just as keen about getting more science out of the space station.

Even before the space station flew, scientists were screaming about its huge expense and the sacrifices they had to make to pay for it, said astronomer-astronaut Stanley Love, part of Atlantis' crew. What's more, space station science doesn't excite many people and keeps getting cut "because we've had to concentrate on getting the thing built," he said.

"Yet we have a facility that's unique, that is expensive, that many governments are contributing to, and why aren't we getting better use out of it?" said Love. Columbus and Kibo will add to the scientific payout. Once construction wraps up in 2010 with the retirement of the space shuttles, the U.S. lab, Destiny, can start generating more science as well, he said.

"This is the way to start recouping our investment in the space station," Love said.

The European Space Agency wants to get at least 10 years out of Columbus in orbit. But NASA plans to pull out of the space station by 2015 to concentrate on lunar exploration, riling those Europeans who have waited so long for Columbus to fly.

ESA will have to rely on its own and other countries' supply ships when that happens, Laurini said. "We are willing to do whatever it takes to conduct as much science as possible," he said.

Columbus will be managed from a control center near Munich, Germany. The official language will be English. That's contrasts with Russian Mission Control outside Moscow, which sticks to Russian in all space station transmissions, requiring a squad of interpreters.

NASA flight controllers in Houston are quick to point out there is no language barrier with their European counterparts.

Space station operations will become more complicated when Europe's first unmanned cargo ship, Jules Verne, is launched early next year from French Guiana, with a control center in Toulouse, France. And the action will really heat up when Japan's lab and control center are added to the mix. It remains to be seen whether English or Japanese will reign.