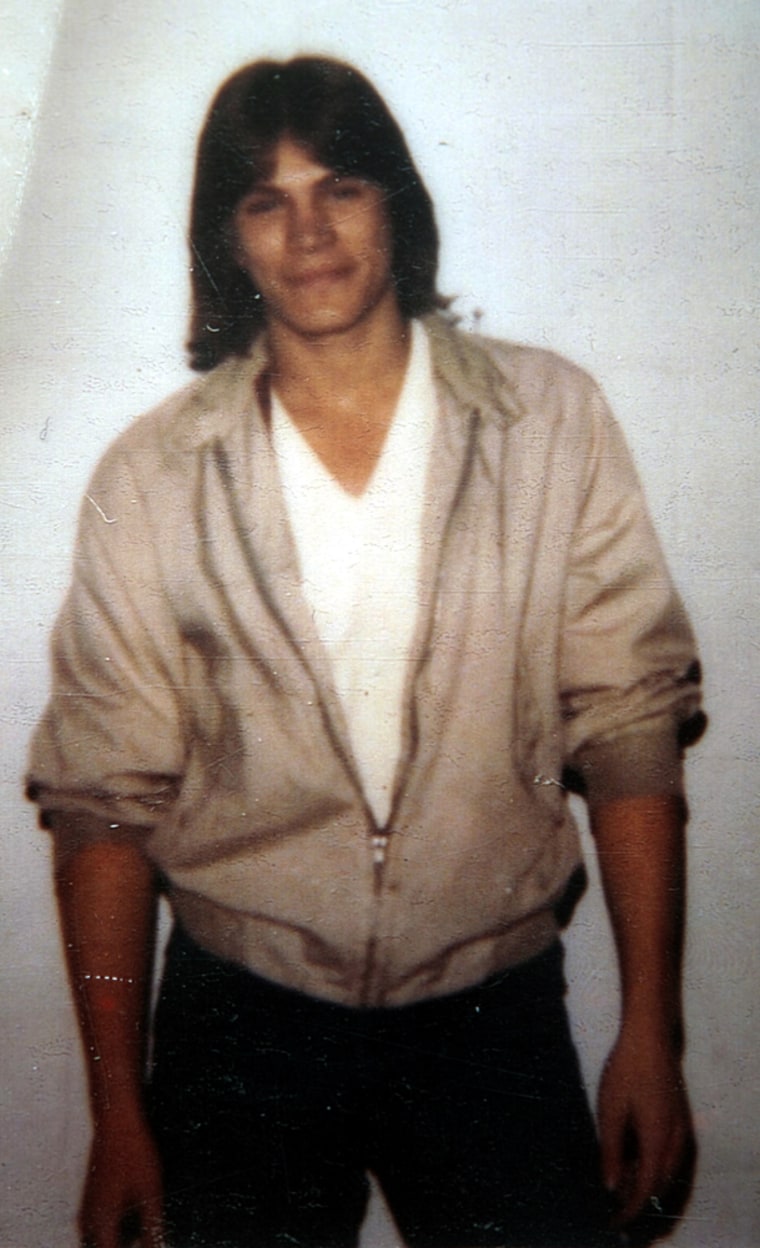

There’s not much left to remember Robert Sellon by. A single, wallet-sized photo tucked into a framed collage. Old newspaper clippings. Many, many memories.

But Tammi Smith doesn’t let go easily. Nearly 26 years after her half brother was murdered, she can still mimic the way he smiled, the way he talked. And she recounts what must have happened the night he was beaten to death in a Grand Rapids pool hall.

The men convicted of killing him have entrusted her with the details.

“I’ve got letter after letter that says if they could do things differently, if they could trade places with my brother, they would,” Smith says, “and I know that’s not just pencil on paper.”

The story of how Smith made her peace with the twin brothers convicted of her half brother’s slaying captures the difficult choices inherent in the debate over sentencing youth offenders to life without parole.

Brothers have blamed each other

It began in October 1981. Sellon was closing the Golden Eight Ball long past midnight. David and Michael Samel, 17-year-old twins, were the last customers inside.

They followed Sellon downstairs, intent on robbing him. When he fought back, investigators said, the Samels beat and strangled him with a hammer and nunchucks. Over the years, each brother has put principal blame on the other.

Michael Samel pleaded guilty to second-degree murder and was sentenced to 35 to 55 years in prison. David Samel was tried, found guilty, and sentenced to life without parole.

Tammi Smith was 15 at the time of the murder. Soon after, she went to the county jail where David Samel was being held, and cursed him for destroying her family. Then she tried to forget.

Learning killers weren't monsters

But six years ago, Smith and her sister realized it wouldn’t be long before Michael Samel came up for parole. They wondered if he had changed. By then Smith was a born-again Christian, newly reflective on the importance of forgiveness.

She sat down and wrote Michael Samel a letter.

He wrote back; later, his brother wrote, too. Over time, Smith and the men convicted of her brother’s murder began talking regularly, sending each other birthday and Christmas cards.

Those conversations convinced Smith her brother’s killers were not monsters but two men who, as teenagers, had made a terrible mistake, their judgment clouded by drugs and immaturity.

“Sending these guys to prison for the rest of their lives is not going to bring my brother back,” she says. “It’s been 25 years, 26 almost. I just think how much more punishment does it need to be? What good is going to come out of this?”

She says she gained 2 brothers

That argument largely echoes one by David Samel, serving life at Ionia Maximum Correctional Facility. Still, he can’t quite make sense of Smith’s forgiveness.

“I’ve got to tell you that sometimes I can’t get my head around that whole thing,” he says. “She’s got a beautiful heart.”

Smith isn’t kidding herself. Many people can’t fathom her point of view. That’s evident when she and her church group go to visit prisons and find even inmates are skeptical. But she hasn’t given up trying to persuade them.

To make her case, Smith lays three photos side by side — Robert Sellon’s, along with David and Michael Samel’s — and asks people to pick out the one of her brother.

“Well, all three of them are,” she explains. “I may have lost one, but I gained two more.”