Just before the start of last week’s All-Star Game, Jim Bunning, a Major League Hall of Fame pitcher and, for the past decade, Kentucky’s junior Republican senator, served up a high inside fastball to Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson, who was on Capitol Hill defending the Bush Administration’s latest effort to bolster the ailing financial system. Cutting Paulson off in mid-sentence, Bunning said, in effect, Mr. Secretary, come next January, you will be gone, but some of us will still be here, and we will have to pick up your tab. I, for one, am not willing to give the federal government a blank check.

Bunning was objecting to Paulson’s proposal that Congress empower the Treasury Department to lend an unspecified, but presumably vast, sum of taxpayers’ money to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the two troubled mortgage lenders. Bunning’s financial logic was questionable—given that the lenders own or guarantee mortgages worth about five trillion dollars, letting them go under is not an option—but his political point wasn’t. Policymakers now face a series of decisions that will determine not merely the fate of this particular cycle but the nature of the federal government’s role in the economy for the next generation.

In a political system as balkanized as ours, it is only in moments of genuine danger that meaningful reforms get enacted. The economic malaise of the nineteen-seventies facilitated the Reagan revolution. The budget crisis of the late nineteen-eighties persuaded first George H. W. Bush and then Bill Clinton to adopt some fiscal discipline, and Congress to go along with them. In some ways, the current situation is more alarming than either of those, but, so far, neither of the Presidential nominees has taken up the call for appropriately bold measures. The best that can be said of John McCain’s economic plan is that it remains a work in progress. Barack Obama has advocated a second stimulus package, together with more aid for struggling homeowners, but the rest of his program was largely put together before the current downturn began.

When the subprime squall swept through Wall Street, last summer, many described it as a “liquidity crisis,” by which they basically meant that, although lenders and investors were too traumatized to put their money at risk, the financial system remained fundamentally sound. Today, we are facing something far more serious: a crisis of solvency. Having lent trillions of dollars to homeowners, developers, and condo-flippers who were busy inflating the largest housing bubble in recent American history, many financial institutions are saddled with huge bad debts. The I.M.F. has called the mortgage imbroglio “the biggest financial crisis in the United States since the Great Depression.’’ Moreover, the banks’ growing reluctance to extend more credit to their remaining customers risks making the situation even worse. Such downward spirals are what turn slumps into depressions.

The government’s response has been to lend to the banks—openly through the Federal Reserve, indirectly through the Federal Home Loan Banks. But lending is only a temporary solution; unless the housing market improves, more drastic measures will be needed. Specifically, the federal government may have to take over the loan books of many stricken institutions, separate the good debts from the bad, sell off the latter to bottom-feeding investors, and recapitalize the businesses that remain so that they can go out and resume lending.

This is essentially what the Resolution Trust Corporation did with hundreds of insolvent savings and loans from 1989 through the early nineties—and this crisis will potentially dwarf that one. It is also what the governments of Norway and Sweden did with many of their biggest banks—which were failing after financing real-estate booms—and shortly afterward those economies were again growing vigorously. (Japan, which was caught in a similar bind, waited a number of years before it finally recapitalized its financial sector at public expense, and it suffered more than a decade of economic stagnation in consequence.)

All of that comes under the heading of crisis management. To insure that we don’t go through the same thing in the next economic upswing, Washington will have to enact a complete regulatory overhaul. For some twenty years, politicians of both parties have been using free-market rhetoric as a cover for favors to big campaign contributors. Starting in the Reagan Administration and culminating in the second Clinton Administration, Congress did away with many of the restrictions on the financial sector that had been in place since the nineteen-thirties, such as a ban on the merging of banks and brokerages. In recent years, predatory lending has gone unchecked, and, with little or no oversight, Wall Street banks bundled subprime home loans into complicated and ultimately toxic securities.

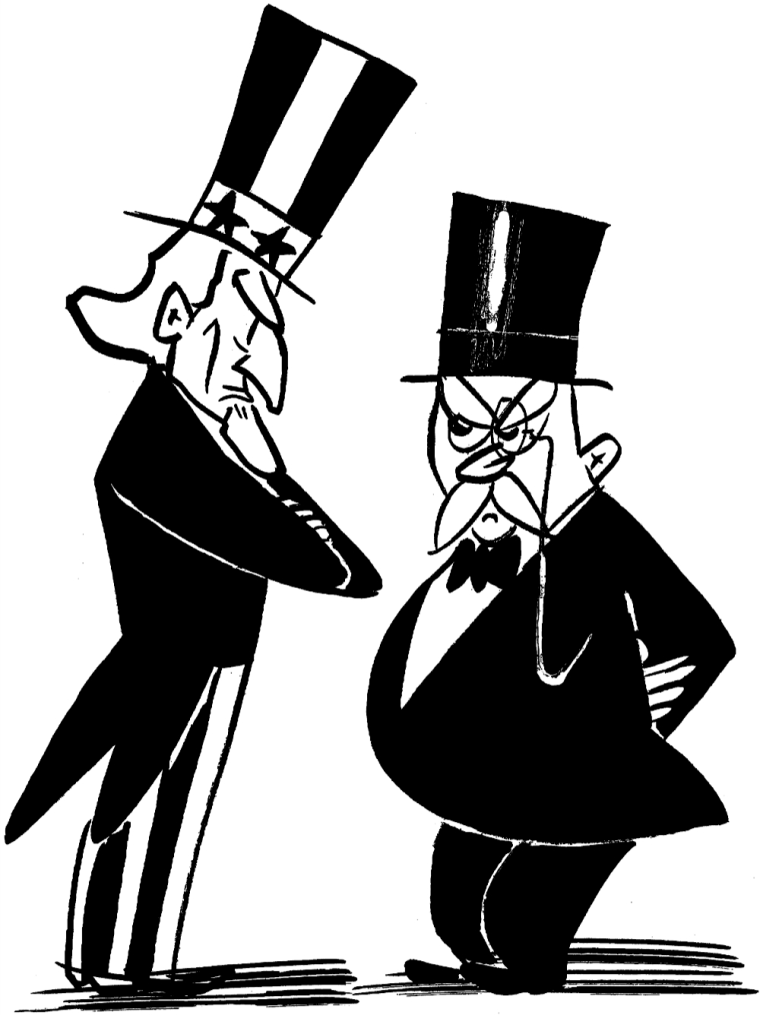

Effective financial regulation often involves limiting the opportunities for short-term profit in the interests of long-term stability. It may be asking too much of McCain, an ardent free marketer and onetime friend of Charles Keating, Jr., the disgraced S. & L. baron—Keating contributed to McCain’s campaigns and flew him around on his private jet (McCain later reimbursed him for the trips)—to crack down on the “malefactors of wealth,” although his recent invocations of Theodore Roosevelt suggest that he at least knows the origin of the term. Obama, perhaps, is a more hopeful case.

Seventy-six years ago, with the country facing the greatest economic calamity of the century, another moderately inclined Democrat saw the need for new thinking and the possibility of radical change. F.D.R.’s “brain trust” provided the intellectual framework for his New Deal speech at the 1932 Convention and for many of the policies that he enacted in his first term—policies that eased the financial crisis, expanded poverty relief, and created a modern regulatory system. The situation today is less extreme, but families face eviction from their homes; workers are losing their jobs; and last week saw long lines of anxious Californians waiting to get their money out of the failed bank IndyMac.

Although Obama has talked about the need for more effective regulation, he hasn’t yet provided many details, and, unlike the two Roosevelts, he has been somewhat reluctant to couple his proposals with a populist critique of American capitalism. During the primary campaign, he won support by making the case that the political system, having been captured by special interests, ignores the welfare of ordinary people. Putting together a similar indictment of the financial system seems like a logical next step, and it would help Obama build a mandate for the reforms that he has proposed, such as expanding health-care coverage, reversing the Bush tax cuts, and investing in alternative energy. Adding to that a coherent plan to deal with the banking crisis and restore the government’s proper role as overseer of the economy wouldn’t amount to a new New Deal, but it would be a good start.