Hoping to prevent convicts from being shut out of the work force, some major U.S. cities are eliminating questions from their job applications that ask whether prospective employees have ever been convicted of a crime.

Most of the cities still conduct background checks after making conditional job offers, but proponents say the new approach will help more convicts find work and reduce the likelihood they will commit new crimes.

"This makes sense in terms of reducing violence. The amount of recidivism — committing crimes again — in this population is dramatic, and it has taken a toll on this community," said John DeStefano, mayor of New Haven, where officials recently proposed a so-called "ban the box" ordinance that drops the criminal-history question from job applications.

Similar measures have been adopted in recent years in Boston, Chicago, Minneapolis, Baltimore, San Francisco, Oakland, Calif., and Norwich, Conn. Los Angeles and other cities are considering doing so.

Some cities such as Chicago continue to conduct criminal background checks for all positions. Others such as Boston do so only when reviewing applicants for school jobs or other sensitive duties.

Life after prison

In New Haven, 25 former prisoners arrive each week after being released. Without help, about 10 of them will return to a life of crime, officials said. The city has some 5,000 residents on probation or parole.

New Haven's existing application asks whether prospective employees have ever been convicted of anything other than minor traffic violations or juvenile offenses.

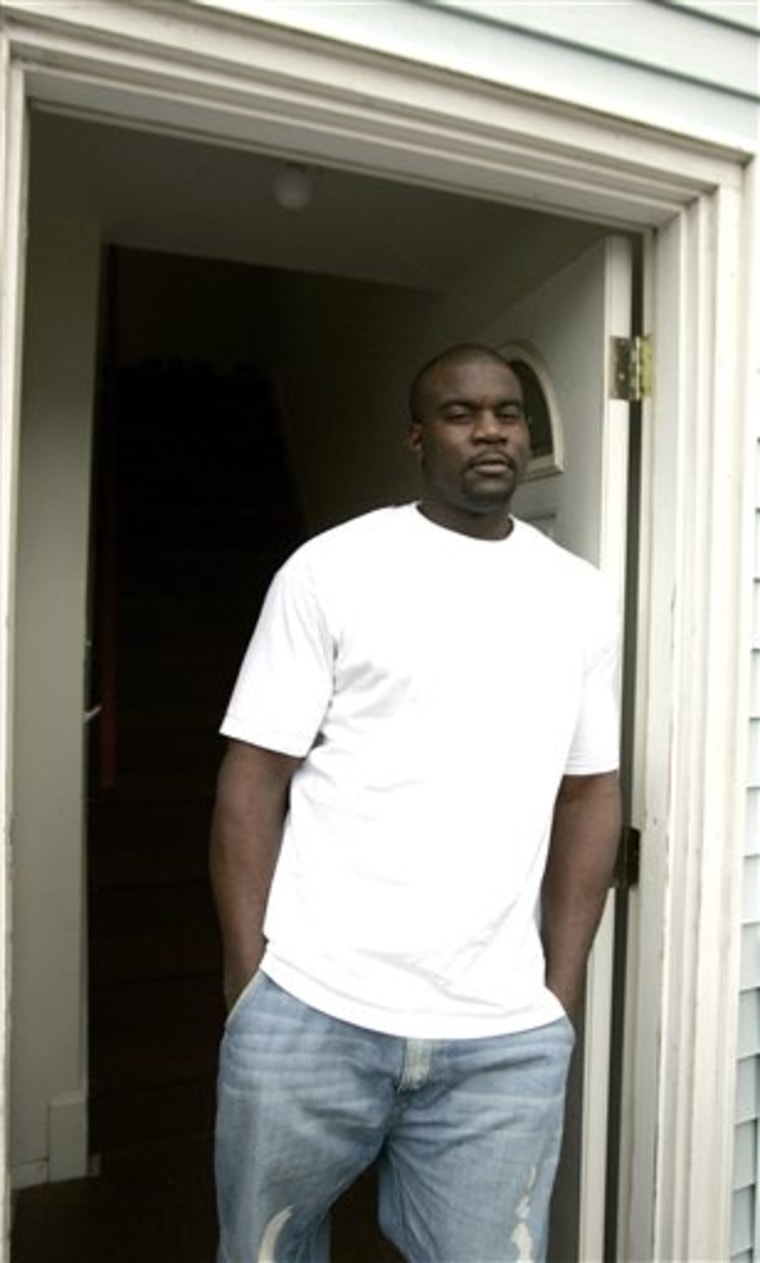

Shelton Tucker, a New Haven resident who served five years in prison for assault with a firearm, said he has lost countless job opportunities because of his record.

"There were some times I was tempted to go back to my old way of making money," Tucker said. "I fell off the wagon a few times. You get stuck with this decision of telling the truth and possibly never being called or lying to get the job and losing it later."

Tucker, who was recently laid off from a glass company because of the weak economy, said eliminating the criminal-history question would encourage more people to apply for jobs. But, he said, the policy will not solve the problem, noting that criminal background checks would still be conducted.

"In a way it's just window dressing," Tucker said.

Cities that have dropped the question could not say how many convicts they have hired. Baltimore has had a hiring freeze since it banned the box nearly a year ago, officials said.

Proponents acknowledge that changing the application is not a panacea, but they insist it allows people with criminal records to get a foot in the door.

'Permanent underclass'

Cities are also creating standards for determining whether a criminal record is relevant to the job.

In Chicago, where more than 20,000 inmates return from prison annually and two-thirds are arrested within three years, the city adopted a hiring policy to balance the nature and severity of the crime with other factors, such as the passage of time and evidence of rehabilitation.

San Francisco also considers factors such as the time elapsed since the conviction and evidence of rehabilitation.

Boston's job application starts with an anti-discrimination statement and lists "ex-offender status" as a classification protected under civil rights laws. The city only does criminal background checks for sensitive positions such as jobs with police, schools, and positions involving large amounts of money or unsupervised contact with children, the disabled and elderly.

Boston officials sent a letter in December requiring companies that do business with the city to comply with that policy.

"What are these folks going to do if they cannot work?" said Larry Mayes, chief of human services for Boston. "You're creating a permanent underclass."

Sending the wrong message?

In New Haven, the changes are part of a broader strategy to help convicts make successful transitions by offering them support with monthly assistance sessions and helping former inmates mentor each other.

But critics worry about the message being sent by the changes.

When the Norwich City Council adopted the policy in December, critics feared it would attract criminals.

Edward Jones, who owns a computer business, opposed the effort, though he said cities should make efforts to ensure everyone is fairly considered for jobs.

"I think they're doing a disservice because this person could end up being in a position of trust," Jones said.

Desperation abounds

Supporters point to a study in October by the Urban Institute that found former prisoners who had jobs and earned higher wages were less likely to return to prison.

When they are released, most inmates start out ambitious to change their lives, Tucker said. But after they are unable to find work, many grow frustrated, he said.

"You start to get desperate," Tucker said. "You go back to what you know."