They are outgunned, outclassed and have almost no air defenses, yet the Iraqi armed forces continue to fight the world’s most powerful military force. Although the tide of battle has always been on the side of the coalition, the Iraqis have not been defeated in an often-cited “cakewalk.”

The Iraqi armed forces, severely battered during the first Gulf War, were able to reform themselves fairly quickly into an effective fighting force. This was due to the fact that most of the destruction of the Iraqi military at the hands of the 1991 coalition was focused on regular army units rather than Saddam Hussein’s better equipped and trained Republican Guard. At the time of the invasion of Kuwait, the Iraqi army consisted of approximately 900,000 men organized into seven corps, and the Republican Guard, which had eight divisions. The Republican Guard was used to seize the entire country of Kuwait in less than five days.

After regular Army forces were used to occupy the country, Republican Guard divisions were pulled back to take up positions behind the regular units to act as tactical and operational reserves as American forces deployed to defend Saudi Arabia.

American operations in the first Gulf War were focused on the liberation of Kuwait. As part of those operations, the U.S. 7th Corps was the only unit with the specific mission of engaging and destroying the Republican Guard. Because the first Bush administration ordered a halt to combat operations after just four days of ground combat, most of the Guard escaped with approximately half of their tanks — mostly capable T-72’s — and artillery intact.

After the war, the Iraqis took a hard look at what went wrong and what went right, the same “lessons learned” process used by military forces worldwide. Virtually all of their combat experiences with the coalition were negative. Force-on-force engagements and open desert fighting resulted in destruction of entire units due to the overwhelming superiority of the U.S.-led coalition’s equipment, technology, tactics, training and logistics support.

The Iraqi air force and navy were effectively destroyed in the opening days of the conflict, and the air defenses — despite French command-and-control integration technology — were systematically defeated. The Iraqis did learn, however, that ballistic missiles are an effective weapon — if not militarily, at least politically. They also determined, correctly, that American military prowess on the battlefield depends on a robust logistics capability.

MEANER, LEANER

In the years after the 1991 war, despite sanctions restricting imports of military hardware, the Iraqi armed forces reorganized themselves into a leaner force, reducing the numbers to about 400,000. Equipment that survived the Gulf War was refitted and cannibalized to support a five-corps regular army and a six-division Republican Guard.

A new unit was created, the Special Republican Guard, charged with the defense of the capital — in reality, protection of Saddam’s inner circle. Of note is the distinct chains of command that were put in place. While the regular army is subordinate to the minister of defense, the Republican Guard and Special Republican Guard were under the direct control of Saddam’s second son, Qusay. This split chain of command is a common anti-coup mechanism seen in many Middle East countries — each serves as a counterbalance to the other. Not to be outdone, Saddam’s oldest son, Uday, created his own militia to protect the regime, the paramilitary Fedayeen Saddam, or “those willing to sacrifice for Saddam.”

Based on their successes in the use of ballistic missiles, specifically the modified Scud, or Al-Hussein, against Saudi Arabia and Israel, the Iraqis embarked on a missile development program that technically kept them in compliance with U.N. restrictions.

Those restrictions limited Iraq’s ballistic missiles to a range of 150 kilometers, or 93 miles. Prior to the 1991 war, Iraqi engineers had proven their skills on a variety of weapons. They:

Modified the Soviet Scud to fly twice its designed range.

Developed sarin and VX nerve agents.

Weaponized the biological agents anthrax and botulinum.

Developed a three-stage intermediate-range ballistic missile prototype.

Developed an AWACS capability by mounting air surveillance radars in cargo aircraft.

Installed refueling capability in Soviet-made fighter aircraft.

After the 1991 war, they applied their expertise to indigenous missile programs. The engineers modified the Soviet-supplied SA-2 surface-to-air missile to be a surface-to-surface missile. These missiles, named the Ababil and Al-Samoud, have been used, albeit ineffectively, against Kuwait and American forces in Kuwait and southern Iraq in the current war.

SMARTLY ADAPTING

More important than the reorganization of the Iraqi armed forces and the development of new missile systems following the 1991 war was the adoption of new tactics aimed at American ground forces, including their supply lines, judged to be the most vulnerable piece of the American war machine.

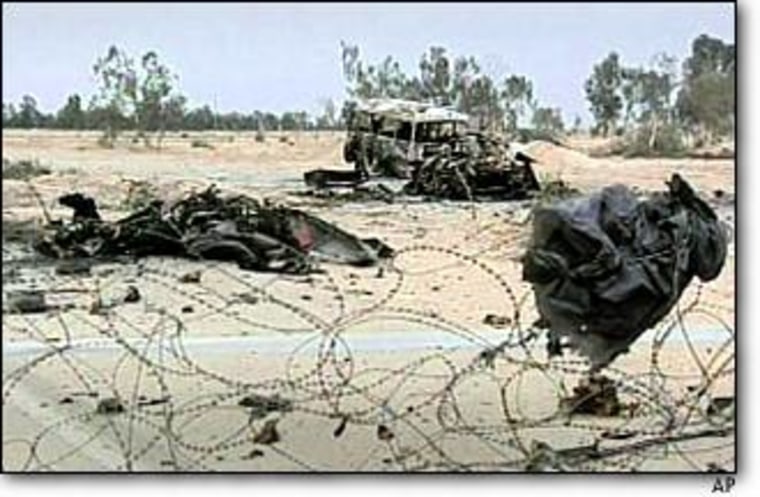

InsertArt(1850270)With the buildup to the current war and Saddam’s successful delaying tactics at the United Nations, the Iraqis had ample time to pre-position their paramilitary forces in cities along the obvious supply route from Kuwait to Baghdad — cities that have become part of the new war lexicon: Umm Qasr, Basra, Nasiriyah and Najaf.

Once ensconced in these cities, the paramilitary units prepared for hit-and-run harassment attacks on American supply lines. They also terrorized the local populations into either resisting — or at least remaining neutral — when the Americans entered the cities.

The Iraqis reportedly used the book “Blackhawk Down” by Mark Bowden, describing Somali tactics against Army Rangers in the mid-1990s, as a planning guide. The use of women and children as human shields, and soldiers dressing in civilian clothes and driving civilian pickups equipped with machine guns and rocket launchers are among the tactics the Iraqis borrowed from the Somalis.

As American forces poured across the border from Kuwait, Iraqi forces did not try to take on American armored units in the field. Instead, they melted back into the cities, having learned the lessons of 1991 perhaps better than the Americans did.

(Rick Francona, a CNBC military analyst, is a former defense attaché to Baghdad and author of “From Ally to Adversary: An Eyewitness Account of Iraq’s Fall From Grace.” )