Welcome to meth country. It’s just past dawn in this farming town of 8,000 in the shadow of Mount Rainier, and a bust is about to go down. This day’s target: a suspected methamphetamine cooker who works out of a shack on his grandmother’s sprawling, cluttered four-acre lot.

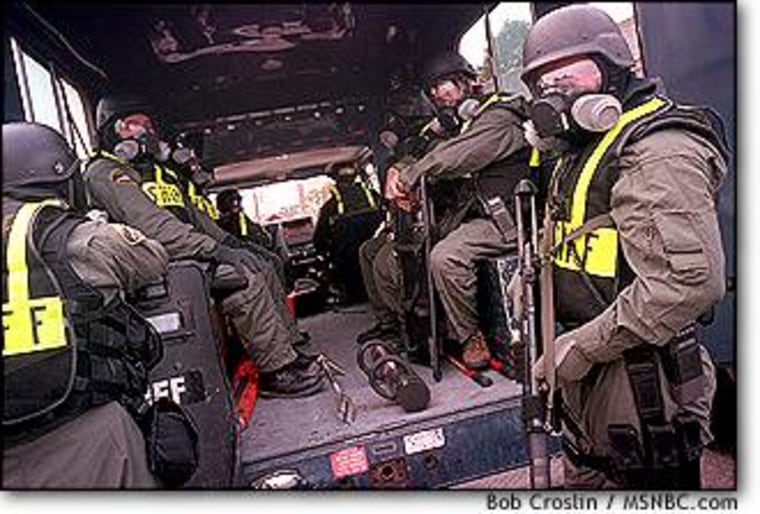

In the town's small courtroom, 20 officers are briefed by sheriff’s Deputy Scott Provost, a member of the sheriff’s meth lab team in Pierce County, whose 689,000 residents are spread out from working-class Tacoma to the desolate peaks of the Cascades. Team members review aerial photos and share details of how the bust will unfold.

“Grandma has no idea what’s going on,” Provost says.

The officers don tactical assault gear — body armor, headsets and helmets — and prepare to head out. It’s the fifth lab discovered in Sumner this year, one police officer says, but only their first bust. “Most of them burn down,” he says.

A convoy of about a dozen vehicles winds its way across town to the bust site. Deputies leap out and shout “Police! Search warrant!” as they bust into the backyard shack where the suspect lives and surround Grandma’s house. The suspect appears taken by surprise and is quickly cuffed.

The deputies, along with local officers and DEA agents, fan out across the property, which is covered with overgrowth and littered with the hulks of rusting trucks and campers. They move through the high brush in a single file, alert for possible snipers or hidden evidence. The sheriff’s raid command center, a modified recreational vehicle with “Pierce County Clandestine Lab Team” painted on the side, pulls into the driveway to process whatever substances the deputies find.

A costly crisis

Nowhere is the small-lab crisis as acute as in Washington state, which has the highest per-capita rate of lab busts in the nation. In 1990, authorities found 38 labs in the state; in 1999, that number had grown to 789. Of those busts, almost half were in Pierce County, believed to be the No. 2 county in the nation in meth lab busts.

Meth is fundamentally a homegrown problem. Though increasing amounts are imported by Mexican drug traffickers or produced in remote “superlabs,” the average producer in rural America is still the small-time cook — usually poor and white — with a dangerous, poorly constructed lab.

The growth of labs has ballooned because the process of making meth is comparatively simple. Meth’s key precursor ingredient is ephedrine or pseudoephedrine — basic ingredients in cold medicine. It can be extracted from over-the-counter pills and cooked down until it’s chemically transformed into the finished product. Thus, most meth starts out as cold pills on the shelf of a local convenience store, easy to find and cheap to buy.

Lab busts, on the other hand, can cost from $1,000 to $10,000 or more, not including costs to assess environmental hazards and do additional cleanup. In Pierce County, the cost for a single cleanup can run as high as $25,000.

Costs are steep because of the toxic nature of the cooking process. Ingredients such as toluene, a paint solvent; anhydrous ammonia, often used as fertilizer; and lithium from batteries can have potentially devastating ecological effects when leaked into soil or groundwater. Health-care workers face chemical exposure when treating meth cooks whose clothing is contaminated. Labs have become so small and so mobile that many cooks hole up in a motel or a cheap apartment, and cleanup costs are passed on to the property owner. Some meth cooks keep their children nearby, potentially exposing them to deadly chemical mixtures; the state’s Child Protective Services just requested $700,000 to hire social workers trained to deal with children who’ve grown up around meth.

“You might think of this as a kind of ecological problem,” says Michael Gorman, who helped run the Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute at the University of Washington and studied meth for the National Institute on Drug Abuse. “I don’t think we really have the total picture here.”

Toxic mess

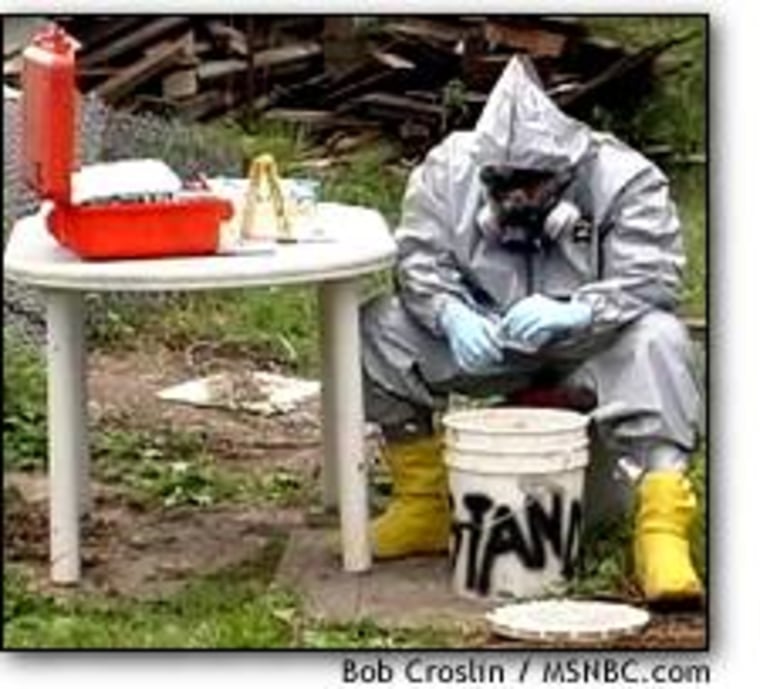

After the Sumner bust, deputies don airtight suits and masks to clear out the lab’s contents. On a tarp, they lay out rusted propane tanks, plastic buckets of chemicals and empty solvent cans.

Every liquid is tested to discover its ingredients, and each item is checked for fingerprints and documented. The suited deputies use radios to log the information with the command center.

Then the materials are destroyed. Propane tanks are taken to a remote shooting range and blown up; compounds are put in a landfill or incinerated; caustic ingredients are Ph-balanced to neutral.

“Judges don’t want that in their courtroom,” explains Sgt. David Perry, supervisor of the Pierce County narcotics unit.

A car pulls up. Grandma has arrived. Indeed, she tells officers she has no idea her grandson allegedly turned her backyard into a drug lab, and she sits crying in the car as a detective explains. She can’t return to her home that night, he informs her — not, in fact, until the health department has made a cleanup assessment and ensured that the property is safe. The process could take weeks, or even months.

Most lab sites are a shambles, largely because meth users have a hard time getting organized and staying focused. The drug also triggers paranoia and extreme sexual urges, and that accounts for other items found during busts.

“You’ll find the drugs, you’ll find the guns, you’ll find filth and you’ll find, a lot of times, pornography,” says Lt. James Chromey, who runs the Washington State Patrol’s Statewide Incident Response Team, or SIRT.

Working on 'crook time'

Pierce County has enough money to run its own meth team, but most of Washington state relies on Chromey and his SIRT officers to help clean up their meth problems. Their efforts are crucial in small towns like Sunnyside, a farm town of 12,000, nestled in the Yakima Valley just about halfway across the state, a region that produces some of the nation’s finest wine grapes. The town’s population — 50 percent Hispanic — demonstrates the confluence that often occurs in meth-prone areas: Working-class whites, who usually cook their own drugs or buy from a close-knit circle of acquaintances, mix with Hispanic workers among whom Mexican drug rings recruit local contacts. High-volume meth production coordinated by drug rings feeds ever-growing demand, while individual cooks remain on the industry’s ground floor.

“The local cooks,” Chromey says, “are Caucasian males, probably 25 to 35 … and unfortunately, most of them are using while they’re cooking. And they’re making mistakes.”

On a sunny September morning, Chromey and members of his team sit in a covert field office outside town and track several suspects. There appear to be no cooking mistakes this day, though an informant claims one alleged cook was complaining about frequent lab fires.

The officers spend hours waiting and tracking the suspects’ movements with the aid of a surveillance plane flying overhead and two patrol snipers who, before the day is over, will have spent 12 hours lying in the high desert nearby, watching the remote lab location.

At last, the snipers call in: The suspects have begun their cook at a lab in remote Bickleton, Wash., near the Oregon border. The officers’ convoy heads out on the 25-mile ride to Bickleton through the desolate Horse Heaven Hills, past miles of burnt scrub and desert. In such remote locations, local law enforcement is often hard-pressed to handle meth arrests and Chromey’s assistance is invaluable.

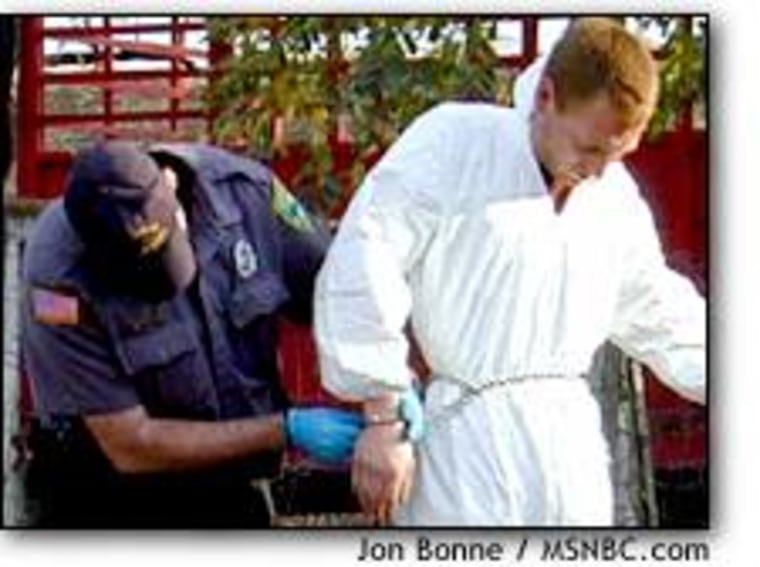

The caravan turns down a two-mile-long driveway. A run-down house sits amid piles of trash. In a nearby trailer, the cops find two suspects engrossed in their work. The third suspect, who is pregnant, is inside the house on the property and has one child with her — with five more expected home from school at any moment. The two alleged cooks are separated from the others; when sheriff’s deputies arrest them, they use thick rubber gloves and dress the two men in white protective suits.

“This is pretty common,” Chromey says, surveying the scene. “Six kids living in this house, and she’s pregnant and she’s cooking meth.”

As authorities make arrangements with Child Protective Services to take custody of the children, Klickitat County Sheriff R.E. Kindler points out this is the fifth bust since June in the county, which has only 19,000 residents. Between 1990 and 1999, only seven labs were found.

Kindler looks around and sighs.

“Here we got all these little kids,” he says. “She’s pregnant. That’s what makes me mad.”