Who wouldn't want a cell phone with a sharper, brighter display than the color LCDs in common use today — especially if it made the phone slimmer and doubled its battery life?

Such displays, using a technology known as Active Matrix-Organic Light-Emitting Diodes, in time could even unroll from a phone in the form of a thin, flexible sheet to display vivid images, games and videos on a screen the size of a cocktail napkin or larger.

Yet even basic AMOLED displays may not be common in handsets any time soon, say some industry analysts, because of limited manufacturing capacity. The 20-year-old technology still hasn't ramped up sufficiently, even for the relatively small displays required by handsets.

The demand is certainly there. Tech-savvy consumers crave screens using AMOLED, which in nearly all respects are superior to LCDs (Liquid Crystal Displays).

They're already appearing in TVs such as Sony's pioneering but puny 11-inch XEL-1 (selling respectably even at $2,500 retail) and LG's announced 15-inch model. Microsoft's new Zune HD incorporates an AMOLED display, as does Toyota's Lexus.

Passive-matrix OLEDs, or PMOLED, are more common but are monochrome and typically used only for simple text displays. The term "OLED," used without a prefix, usually refers to AMOLED.

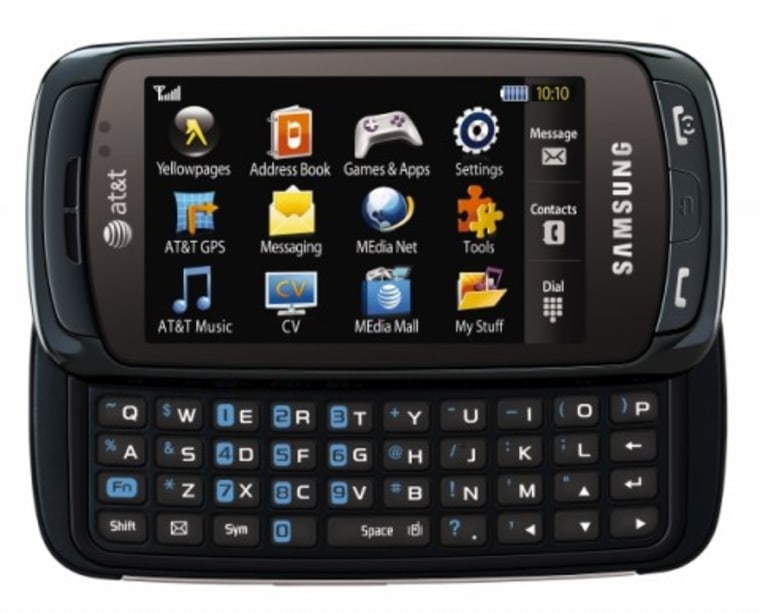

OLED has found its way into a few handsets available in the United States, including Nokia's N85, Samsung's Impression (through AT&T) and newly announced Rogue (through Verizon Wireless), with many more on the market in Asia. N85 buyers on Amazon.com laud the display as "brilliant" and "bright and easily readable," though one criticized it for turning grays into browns.

OLED is a 'differentiator'

Samsung plans to use OLEDs in the Omnia 2, set for U.S. release this year, and it might announce other OLED-based handsets within the next month, said Samsung Senior VP Omar Khan.

"Right now OLED is a differentiator in our premium-tier phones, but I do imagine a time when OLED phones are the norm," Khan said.

OLEDs are attracting attention outside the electronics industry, too, in the world of lighting. A recent New York Times article described OLEDs' adoption by designers because they're long-lasting, energy-efficient, bendable and can illuminate in a wide range of colors.

"At the moment, there's no display technology on the horizon that could eclipse OLEDs," said Gartner analyst Paul O'Donovan.

OLEDs offer numerous advantages over the LCDs now used as the primary displays in many cell phones and digital music players.

OLEDs yield colors that are brighter, deeper and more natural than those from LCDs. Sony says its OLED TV can display a wider range of more colors than are prescribed as standard for U.S. television by the National Television Systems Committee.

They offer higher contrast levels than LCDs, which makes for crisper images. The stated contrast ratio for some OLEDs is 1 million to one, meaning the darkest dark is 1 million times darker than the lightest tone. In comparison, LCD contrast levels range between 1 and 5 percent of that figure, depending on the manufacturer.

OLEDs virtually eliminate the blurring and strobing that can occur on LCD screens when objects move quickly across the screen. And they have a wider viewing angle than LCDs, allowing several people to successfully see a screen from varied positions.

They also consume roughly half the power of LCDs, depending on what's being displayed. That means a phone's battery life could be doubled even without improvements in battery technology.

Light that lasts

One OLED shortcoming is that the displays wear out more quickly than LCDs. Television LCDs last 50,000 to 60,000 hours, according to manufacturers' claims, though their backlights can burn out, and as they deteriorate, the colors can change in hue.

OLEDs' phosphors — the substances that make them emit light — have shorter lives than that, with blue phosphors the shortest-lived of all. It's hard to put a number to their lifespan because it's increasing rapidly with research.

But PMOLED maker RiT Display Corp. estimates OLEDs with a lifespan of just 7,000 hours would last most cell-phone users nine years — far longer than most people own their phones, and long enough to even recycle the phone through several users.

Unlike LCDs, OLEDs can be created on flexible surfaces. Today they're usually created on glass substrates, making them rigid. But researchers are creating them on bendable plastic and on metal foil, either of which will reduce their weight and fragility.

Large, flexible, roll-out screens are three to five years away from the marketplace, said Janice Mahon, a vice president at OLED component maker Universal Display Corp. in Princeton, N.J.

Flexible-screen OLEDs "will tremendously change product designs," Mahon said. "When the necessary manufacturing capacity is in place for those, people will say, 'Why do I want a glass-based equivalent?' "

Limited availability now

With all those advantages, why aren't OLEDs more popular on handsets?

Vinita Jakhanwal, an analyst with iSuppli Corp., said OLEDs will account for only 6 percent of handsets' primary displays in 2013, up from 2 percent this year.

Gartner's O'Donovan disagrees, saying OLEDs will be on 20 percent to 30 percent of conventional handsets within three years, with so-called smartphones lagging behind because they have bigger, and therefore more costly, displays.

The main factor is limited availability. Only one factory, owned by Samsung Mobile Displays, is currently making AMOLED displays. Built six years ago at a cost of at least $1 billion, it's still not profitable, Jakhanwal said. A second AMOLED factory, owned by LG, is due to begin production soon.

Compare that to 25 or more factories creating LCDs. And those factories can churn out 90,000 sheets of display material a month, compared with the OLED factory's 20,000 sheets a month.

"OLEDs are so much newer, so the manufacturing techniques are still expensive," said Jakhanwal.

Samsung plans to double its OLED production next year and to build a larger factory as well. But those plans could be jeopardized by the worldwide recession, which Jakhanwal said led several companies that had been planning to produce OLEDs to bail on their plans.

The scarcity and high cost of OLEDs are even delaying Sony's plans to build a 27-inch OLED TV. And LCD makers are hoping to stem an OLED tide by developing new, thinner LCD technology.

Assuming manufacturing capacity does increase — and most believe it will — OLEDs will be even less expensive than LCDs, believes O'Donovan, because they use fewer parts.

Phones are 'right market'

Even the LCD industry grudgingly foresees a strong future for OLEDs, at least in cell phones.

"For 10 or 15 years, the OLED industry has been about to break out, and it's still a $0 billion industry," said Bruce Berkoff, chairman of the LCD TV Association.

"I don't think they're about to displace the $150 billion LCD industry, but I think handsets and small devices are the right market for OLEDs, as opposed to TVs, because you can have a small percentage play and still be large enough to make an impact."

OLED illustration courtesy of OLED-display.net.