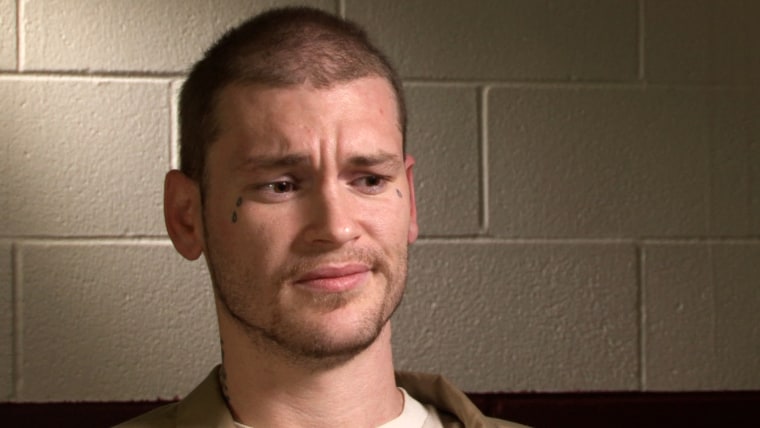

The life of David Goble, already a weathered man at the age of 27, chronicles the cost of methamphetamines in this area — both human and financial.

The Goshen, Ind., native used drugs as a teen, but it was the powerful high of meth, which he started using heavily with coworkers at a local trailer factory, that drove him off the rails.

High, and ever in the pursuit of the next high, Goble would stay awake for days on end, committing burglary to fund his habit, and for thrills. For most of the past decade, he has cycled in and out of jail and prison. When he was booked for the last time into Elkhart County Jail, he was strung out and emaciated.

Now, Goble is in a program to get clean of meth and crime called CLIFF — in a cell block entirely devoted to meth addicts in this maximum security prison.

“I really want to live a clean life to where I ain’t gotta get up and just get high or get up and feel like just going out and doing something stupid,” said Goble. Tears well up in his eyes next to the tears tattooed on his cheek bones, as he recalls a promise he made to his dying grandfather. “I decided I was gonna come (into the CLIFF program) and do what I could to better myself and hold a promise to him to be better and not come back.”

Goble’s struggle is a small window into a costly national problem.

Substance abuse and addiction cost federal, state and local governments at least $467 billion annually, according to a recent study by the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University. Nearly 96 percent of that is spent on the “human wreckage” of substance abuse — including drug-related crime, incarceration, health care, foster care. About 1.9 percent goes to prevention and treatment, the report says.

Due to recession-fed state and local budget problems, the law enforcement, court, and prison systems in most states are strapped. At the same time, drug treatment and prevention programs — underfunded, advocates say, even in better times — are struggling with shrinking resources.

“The recession has been really tough for providers as well as patients,” said Daniel Guarnera, director of government relations for NAADAC, a national association for addiction professionals.

In Elkhart, meth is not the only illegal drug, but it is the one that has dealt the hardest blow to its working class gut, bringing down many men and women who staff the area’s RV factories. Over the course of the recession, at least one aspect of the problem has worsened: By mid-November of this year, Elkhart County had discovered more than 100 meth labs, compared to 75 in 2008, and 77 from 1999 through 2006, according to State Police records.

Meth tsunami

The first big wave of meth arrived in Elkhart in 2002, coming in the form of highly refined “crystal meth” that flooded the market as Mexican drug-trafficking organizations moved into the Midwest from the West and Southwest. The very things that made Elkhart a good site for manufacturing RVs also made it an excellent distribution point for illegal drugs. The county straddles the Interstate 80-90 corridor that connects the West coast to nearby Chicago and points eastward — Cleveland, Detroit and New York.

A single meth high — from smoking, shooting up or snorting — can last four to eight hours, and a persistent user can stay awake for days or even weeks at a time. Just as the stimulant tends to appeal to long-haul truck drivers, factory workers embraced meth to help them work long shifts or produce faster for piece-rate pay. Workers like Goble were buying and using in the factory parking lots on breaks.

“I think there was a certain perception at the beginning that this wasn’t so awful bad,” said Bill Wargo, chief investigator for the Elkhart County prosecutor’s office. “I literally did talk to an RV manufacturing facility group of supervisors who sat there and said, you know, these guys really work fast when they are on meth.”

Most Elkhart residents, including factory managers, quickly realized that any upside of meth use was short-lived. Many users ended up addicted, without jobs, and cut off from their families.

“There have always been guys who are using, not extremely heavy to where it wrecks their life. They use it on the job to increase their productivity,” said Ken Norman, who directs outpatient services at Oaklawn, a nonprofit mental health center in Elkhart County that is dealing with a growing number of meth addicts. “But most people, especially with meth, eventually do spiral down, and end up using heavier and heavier.”

Goble is an example of the downward spiral.

“I stayed up for months at a time, not eating, just getting hallucinations… you really start to go crazy after a while,” he said of the period leading up to his arrest in April 2008, after he had learned to produce meth. “You start doing things you wouldn’t normally do… You just stop caring about things that you should be caring about.”

Ever-shifting target

Local officials started beefing up their pursuit of methamphetamine trafficking in the mid-2000s. Between 2005 and 2008, a series of arrests by the Elkhart County drug unit — a joint force made up of police from the cities, and county enforcers — working with the federal Drug Enforcement Administration and police in neighboring counties, brought down more than a dozen key players of a Mexican drug ring, seizing loads of pure, uncut meth, along with cash and other drugs.

At the same time, the federal government put in place restrictions on the import of meth’s active ingredient, pseudoephedrine, and cold tablets that contain this ingredient. The United States also worked to limit and monitor large pseudoephedrine shipments to Mexico, where industrial-sized labs were producing meth by the ton — much of it destined for U.S. markets.

As a result of these efforts, imported crystal meth is now scarce here. But the problem has merely changed shape. In the last two years, Elkhart County has witnessed a surge in homemade meth production, with makeshift “labs” springing up in homes, trailers, cars, even backpacks.

The cook is typically producing just enough for himself and a circle of friends or family. Some in the circle go out to “smurf” — going from one pharmacy to another to steal or buy cold tablets, which are ground up and combined with chemicals to leach out the pseudoephedrine. Others gather the chemicals to extract the pseudoephedrine. They produce a few grams in a batch — imagine a packet or two of sugar packets on a dinner table — and then begin the process all over again.

New rules

The burgeoning number of meth labs has been a game changer for law enforcement, said Elkhart County prosecutor Curtis T. Hill Jr.

“When you’re dealing with the imported meth, you’re dealing with business people,” Hill said. “These are all, for the most part, individual labs of people who are addressing their own needs or the needs of their near friends and associates. It’s a much more difficult nut to crack from a law enforcement standpoint.”

In the last year, the scale of drug-producing operations has gotten even smaller, with the advent of the one-pot or shake-and-bake method of making meth. A slightly different formulation of chemicals and lithium battery strips are mixed up with the crushed cold tablets in a plastic jug, say a liter-sized plastic soda bottle; the active ingredient can then be extracted with coffee filters.

Each time local authorities find an active lab, they are required to call in people certified to handle the hazardous substances. In Elkhart and neighboring counties, that’s Mike Toles, one of 18 state troopers assigned to the Indiana Methamphetamine Suppression Section. Toles says he finds meth trash left behind in ditches and dumpsters on a daily basis — signs that authorities are getting only a fraction of the users and makers.

“It can be done in a vehicle, it can be done in a trench coat walking down the street, it can be done in a moped, in a shed, in a fence row behind a school, it can be done just about anywhere,” said Toles.

Though usually small, mobile “labs” are still toxic and potentially explosive, and still expensive to dispense with safely. It costs between $1,200 and $1,500 each time Toles and his colleagues dismantle a lab and dispose of the hazardous materials. Toles covers the northern part of Indiana, including Elkhart and parts of two neighboring counties, some days cleaning up as many as seven labs, he said.

When labs are set up in buildings, the costs often go well beyond the lab removal itself. Children found at these sites are whisked off by the men in hazmat suits for immediate medical attention, treated for exposure to the chemicals, and then usually placed in foster care.

The home, apartment or hotel room is usually contaminated with toxic chemicals that permeate walls, carpets, furniture and heating systems. Property owners are liable for thousands of dollars to remediate the mess. If the property owner can’t afford it, and many can’t, the house often remains vacant. Of some 75 buildings, mostly homes, identified by the Elkhart County Health Department as contaminated by meth production since 2007, nearly half remain empty, contaminated, and condemned.

Tough prosecution

Hill, the county prosecutor, takes a hard line on meth, with no apologies.

“When that house blows up and it has someone in the house that is innocent, like a child, or someone next door,” says Hill. “Then there’s a danger of houses that are being raided and closed down… (are) still sitting there months or years later with tape or a ‘do not enter’ sticker. … That’s how neighborhoods start to decline.”

Under a state law passed in 2005, sentencing for meth possession and production got stiffer. But tough prosecution means more pressure on the corrections system.

That’s one reason Elkhart County Sheriff Mike Books has filled up an 890-bed jail, built at a cost of $90 million and opened just two years ago to replace an old, overcrowded facility. He estimates 75 percent of the people in the facility are there for crimes related either directly or indirectly related to drugs — often meth.

The county is responsible for providing health care of offenders booked into the jail, and has a $2 million annual budget for that, Books said. And drug abusers, especially meth users run up costs quickly. They frequently have a mouth full of corroded teeth, which can cost $12,000 in dental care alone, he said. They may also need treatment for everything from withdrawal and skin lesions to kidney damage, running up bills in the tens of thousands of dollars.

When these drug offenders are kicked up the line to prison, it usually doesn’t get any easier to break the pattern — and high cost — of drug use, crime and incarceration. Indeed, one inmate in the CLIFF program at Miami, 27-year-old Paul Rice, said it was while serving a previous sentence at Indiana’s Branchville Correctional Facility that he learned how to make meth from other inmates while out on road crews and that he used heavily while he was in the prison.

Chronic underfunding

Sheriff Books has done his own back-of-the envelope calculation about the costs of booking the same people into jail time after time, and he says he’d like to see more drug treatment and other programs in the jail to lower recidivism — which he says is 60 to 65 percent in Elkhart. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services estimates that each $1 invested in drug and alcohol treatment saves about $7 in criminal justice costs and nearly twice that when health care savings are included.

“You can’t just look at it as warehousing folks, or we will just keep building bigger jails,” said Books.

But getting approval for funding drug treatment programs has always been difficult here — many people don’t see reason to spend money on addicts — and is even more challenging during recession.

“There’s no question that the weak link in our system in substance abuse assistance,” said Books. “Recession certainly impacts tax dollars. Tax dollars pays for services and services diminish when we don’t have the dollars to do that. It’s a Catch-22 situation.”

In Elkhart, one early casualty of budget cuts is a team that evaluated substance abusers for the drug court, which diverts low-level offenders who meet certain criteria to treatment and monitoring rather than jail. The program, with a staff of eight, used to assess and monitor 800 to 900 clients a year, according to director Scott Filley. After Jan. 1, the workload will likely fall upon overburdened probation officers or to the private sector.

Limited help is available from the federal government. While there was nothing in the stimulus bill specifically targeting drug treatment, the legislation did include $2 billion for broad application in the fight against crime, from investigating drug-trafficking organizations to drug rehab. Elkhart County is slated to receive $264,000 of these funds, and has so far spent about $96,000 of the total to buy patrol vehicles and video equipment, according to the Web site, www.Recovery.gov.

By all accounts, the 2010 federal budget will eliminate the 25-year-old Safe and Drug Free Schools State Grants program, funded at $295 million last year — money that was used for drug and violence prevention programs. At the same time, the budget will almost certainly increase funding for drug courts, from a current level of $63 million. In recent years, many legislators have embraced the courts as a cost-saving way of handling non-violent drug offenders.

New approach to treatment

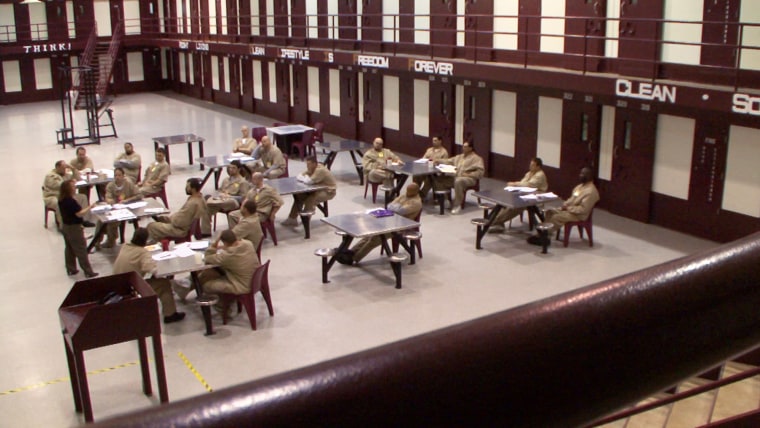

Along with the entire Indiana prison system, CLIFF — the fledgling treatment program where Goble and other inmates are being treated — is feeling budgetary pressures. Staffers that leave CLIFF are not easily replaced, so remaining counselors work grueling shifts. And, because the rest of the prison is overcrowded, the CLIFF cell block is sometimes forced to temporarily take on prisoners from the general population – which can make harder to keep the CLIFF participants on track, said Patricia Pretorius, the program’s director at Miami.

"Everybody here is focused on their recovery, which is hopefully not going to be the negative behaviors you were surrounded by in general population,” Pretorius said. “We teach them that from the time you wake up in the morning to the time they go to bed at night, it’s all about your recovery.”

Goble, who is serving a six-year term, is in for a burglary — not specifically for meth in this case, but his meth-addiction is viewed as his core problem, so he was qualified to join the program. He and other prisoners who qualify for CLIFF have joined it voluntarily.

In this cell block of about 200 beds, participants agree to a rigorous schedule, which starts with a military-style inspection first thing in the morning, followed by a full day of substance-abuse counseling, classes, study and peer group sessions.

Pretorius said the program is making a difference. Recidivism among offenders who have gone through the CLIFF programs in four programs statewide is about 24 percent, compared to 37 percent in the general population, she said.

That gives a guy like Goble a fighting chance to escape the meth-saturated world he has occupied.

“You learn things about yourself that you wouldn’t look into... all the people you hurt... or how bad your health really is," Goble said of the program. "I’m hoping to get tools out of it that make me live a better life than what I was living.”