AT&T says it has worked hard to improve its much-maligned third-generation (3G) network over the last eight months — erecting hundreds of new cell towers, using better-performing wireless spectrum, and souping up its cell sites across the country — and the results of our latest 13-city, 3G network performance tests suggest that the network has indeed undergone a drastic makeover.

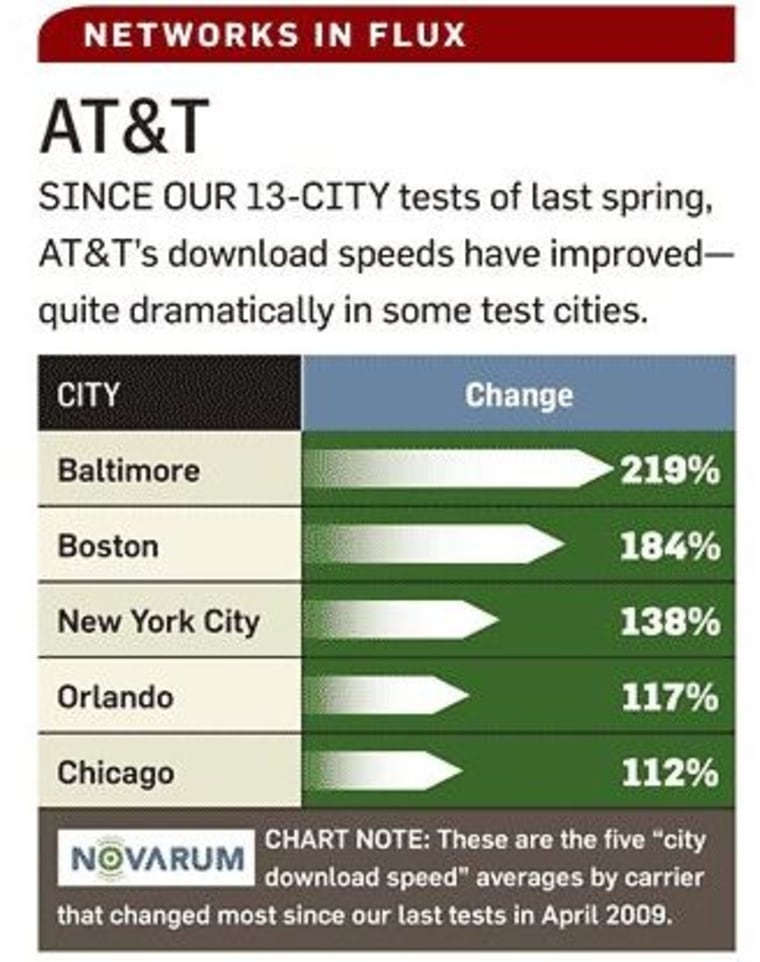

After registering the lowest average download speeds in our 3G performance tests last spring, AT&T’s network turned in download speeds that were 84 percent better than the numbers from eight months ago; in our latest tests, AT&T's download speeds were 67 percent faster on average than those of the other three largest U.S. wireless providers — Sprint, T-Mobile and Verizon.

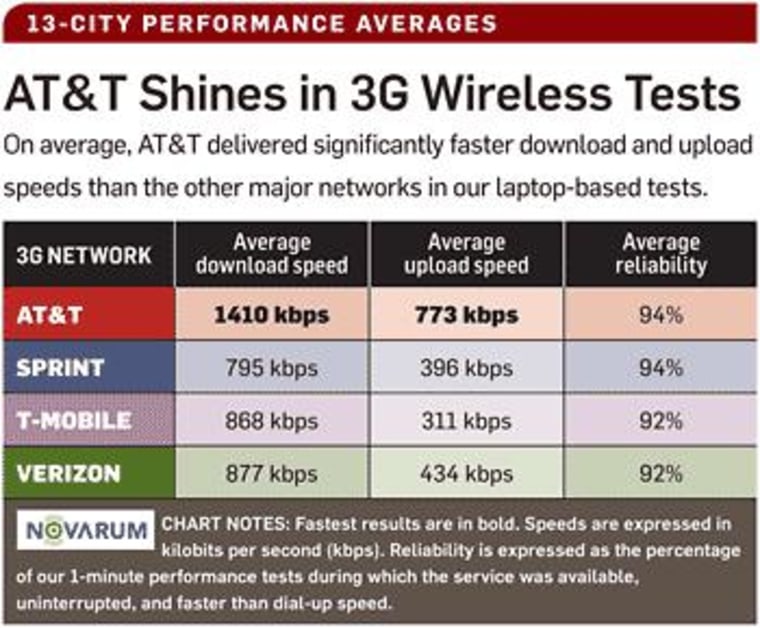

In our tests last spring, AT&T posted an average download speed of 818 kbps (kilobits per second) across 13 cities. In our tests conducted in December 2009 and January 2010, AT&T’s average download speed increased to 1,410 kbps.

AT&T's download speeds in New York City were three times faster in our latest tests than in our tests last spring; in San Francisco, the AT&T's download speeds were 40 percent faster.

Network reliability much better

The AT&T network’s reliability improved dramatically, too: Last spring, PCWorld testers obtained a usable broadband connection with AT&T only 68 percent of the time. In our latest tests, testers connected to AT&T successfully in 94 percent of their attempts.

Verizon Wireless, which turned in the best all-around performance in last spring's 3G network testing, and Sprint, which finished a close second, both continue to perform well, according to our latest test results. Our tests found that Sprint’s network delivered download speeds nearly identical to those we measured eight months ago in the 13 test cities; Verizon’s download speeds decreased by 8 percent overall.

In the past year, Sprint and Verizon — like AT&T — have seen a marked increase in the number of 3G smartphones that rely on their networks.

Our speed results suggest that Sprint is upgrading its network capacity fast enough to meet the demand, while Verizon may be having trouble keeping up. Nevertheless, both networks’ reliability (the likelihood that a user can connect to the Internet at a reasonable speed) improved in the most recent tests over how they fared last spring.

We tested the T-Mobile 3G network for the first time in December and January, and found that it supported download and upload speeds that were competitive with Sprint’s and Verizon’s in most of our test cities. In one city — New York — T-Mobile’s network even delivered download speeds that are usually associated with 4G networks.

Testing that was done

Before getting into the details of our test results, a few words about the testing and the data. During December and January, PCWorld and our testing partner, Novarum Inc., tested the download speeds, upload speeds, and network dependability of the AT&T, Sprint, T-Mobile, and Verizon 3G networks from 20 locations in each of 13 U.S. cities.

Click here to see the detailed results of our laptop-based testing of the Big Four 3G wireless networks (AT&T, Sprint, T-Mobile, and Verizon) in 13 U.S. cities.

Click here for the detailed results of our smartphone-based testing of the Big Four 3G wireless networks in 13 cities.

Altogether we ran more than 51,000 separate tests covering 850 square miles of wireless cell coverage servicing 7 million wireless subscribers (see “How We Do the Testing”).

At each testing location, we connected to the 3G network via both laptops and smartphones. The laptop tests accurately measured the capacity and performance potential of a given network, while the smartphone tests approximated the real-world connection speeds users of these popular devices might experience, given the less-powerful processors and 3G radios that the devices contain.

Because we couldn't test every city in the country, we chose 13 that are broadly representative of the rest: Baltimore, Boston, Chicago, Denver, New Orleans, New York City, Orlando, Phoenix, Portland, San Diego, San Francisco, San Jose, and Seattle.

Because wireless signal quality depends to a large extent on variables such as network load, distance from the nearest cell tower, weather, and time of day, our results can’t be used to predict specific future performance in a specific area. Rather, they illustrate the relative performance of 3G service in a given city on a given day. Each speed number possesses a margin of error of plus or minus 5 percent.

AT&T’s dramatic 3G makeover

Our most recent tests showed that the connection speeds delivered by AT&T's network — both downloads and uploads — increased considerably in every one of our test cities, compared with the speeds it registered in identical tests we conducted last spring.

In Baltimore, New York City, New Orleans, Portland, and Seattle, AT&T’s average download speeds in our tests more than doubled.

The network’s 13-city average download speed was 1.4 mbps; that’s as fast as many home broadband connections. In our tests, none of AT&T’s three biggest competitors registered average download speeds of better than 1 mbps.

In our Baltimore, Boston, and New York tests, AT&T’s HSPA network delivered burst speeds exceeding 4,000 kbps — a top speed that Sprint and Verizon can’t match with their current 3G technology, CDMA EvDO Rev. A.

AT&T’s upload speeds were one of the few bright spots in its test results last spring, and the network continued to deliver the fastest upload speeds of the Big Four networks in our latest tests.

AT&T upload speeds increased by 58 percent and now average 773 kbps — that’s 330 kbps faster than the average upload speed we clocked for Verizon, the second-fastest network.

Testing the iPhone on AT&T

Our smartphone-based tests of the AT&T network told the same story as our laptop-based tests, though they also revealed the speed limitations of smartphones in general, especially when the devices are uploading data to the network.

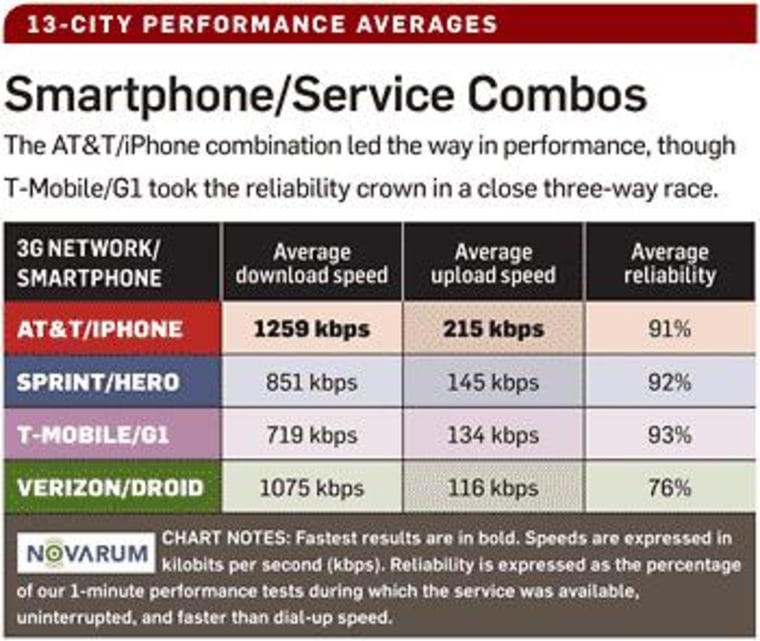

The AT&T and iPhone combo turned in the fastest average speeds — downstream and upstream — of the four carrier/smartphone combinations we tested, outperforming its rivals in more than three-fourths of the cities we sampled.

AT&T connected the iPhone at an average download speed of 1,259 kbps, and an average upload speed of 215 kbps over the 13 testing cities. The iPhone clocked download speeds of at least 1,000 kbps in more than 60 percent of our testing locations, with burst rates often exceeding 3,000 kbps, and we managed to obtain a reliable connection in 91 percent of our AT&T/iPhone tests.

What happened?

AT&T appears to have added considerable data service capacity during a year when its wireless subscriber base grew considerably, as did the amount of data service those subscribers use.

During 2009, AT&T's total subscriber count swelled from 77 million to more than 85 million, with a growing proportion of those subscribers — 40 percent, AT&T says — now using smartphones.

And of AT&T's 85 million subscribers, 10.3 million now connect to the network using an iPhone, which seems to invite users to perform bandwidth-intensive activities such as Web browsing and video streaming.

“On the AT&T network, we’re seeing advanced smartphones like the iPhone driving up to 10 times the amount of usage of other devices on average,” says AT&T spokesperson Jenny Bridges.

At the time of our first 3G network test last spring, AT&T's premier device — the iPhone — had become both a blessing and a curse: The company’s coup of becoming the exclusive service provider for the iPhone undoubtedly helped swell the customer base for its wireless services. But the iPhone also seriously challenged AT&T’s data network resources, especially in iPhone-happy places like San Francisco and New York City.

Shortly after we revealed the results of our spring 2009 tests, AT&T announced plans to increase the speed of its 3G service. To achieve this goal, AT&T said, it would upgrade its networks to the faster High Speed Packet Access (HSPA) 7.2 technology (thereby doubling the maximum speeds of upgraded cell sites), utilize better-performing portions of the wireless spectrum, increase backhaul capacity, and add new cell towers.

Improvements ahead of schedule

In a recent conference call with investors, AT&T head of operations John Stankey said that the company had finished upgrading its network to HSPA 7.2 technology far ahead of schedule.

“We have already turned up the 7.2 software on our 3G cell sites nationwide,” Stankey said on the call. He also pointed out that AT&T had added 1,900 new cell sites and had converted its network to the 850MHz spectrum band during 2009.

The combination of these improvements probably accounts for the large speed increases we saw in our recent tests.

“It is clear that at this time AT&T has the highest-performing network with the highest user capacity, based on our sample,” says Novarum CTO Ken Biba, who conducted the tests.

“With the additional investment in HSPA 7.2 base stations (last year) and high-speed backhaul infrastructure, AT&T has room for growth in demand.” Biba says.

“However, demand will only accelerate with the iPad, e-readers, streaming video, and new mobile applications. Will AT&T have enough capacity with HSPA 7.2? Will the transition to LTE (a 4G, or fourth-generation, wireless technology) happen fast enough? These are all key questions for 2010.”

Verizon: Signal fading slightly

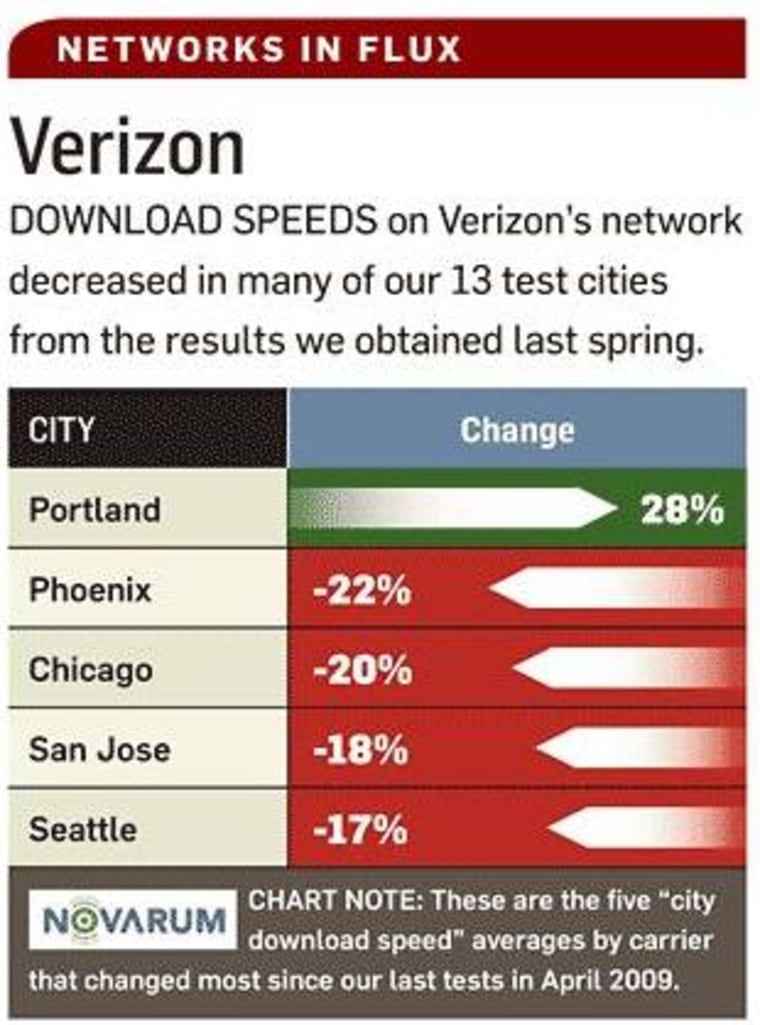

We measured Verizon’s 13-city average download speed at 877 kbps, down 8 percent from its average of 951 kbps in our tests last spring.

Verizon’s average download speed decreased in seven of 12 of our testing cities compared to the figures we recorded last spring; and in five of those cities — Chicago, New Orleans, Phoenix, San Jose, and Seattle — Verizon’s average dropped by 15 percent or more.

Verizon had the best-performing network in our tests last spring, with the fastest overall speeds and strong network reliability. But our recent test results suggest that Verizon may not be keeping up with demand in some markets.

Verizon is a bit later than its competitors to the game of supporting bandwidth-hungry smartphones on its network. Verizon says that only 15 percent of its postpaid customers (customers with service contracts) owned smartphones at the end of 2009, compared to AT&T’s 40 percent.

But increasingly, Verizon subscribers are using smarter phones that demand more broadband data service. Verizon says that its data service revenues grew from $12 billion in 2008 to $16 billion in 2009. The company's data service business will continue to grow as phones like the Motorola Droid (which reached market in November 2009) proliferate and begin taking a toll on network capacity.

In our recent tests, Verizon’s average upload speeds showed little change from our results last spring, averaging 434 kbps. Nevertheless, we saw significant changes for Verizon in some cities: Average upload speeds decreased by 21 percent in San Diego, but increased by 27 percent in Denver and by 16 percent in New York City.

Verizon’s network reliability scores in our recent tests were a mixed bag: Verizon's scores fell by 12 percent in both Baltimore and San Diego, compared with its scores in those two cities in our tests last spring. Yet in Chicago, Orlando, Phoenix, Portland, and San Francisco, the company's reliability scores increased by more than 10 percent.

Verizon promises its wireless customers typical download speeds of between 600 kbps and 1.4 mbps — and in the vast majority of our tests, it delivered. Upload speeds were a different story, however. Verizon promises upload speeds of from 500 to 800 kbps, yet in only one of our 13 cities (New Orleans) did we record an average upload speed of more than 500 kbps during our laptop-based tests.

Testing the Droid on Verizon

Our smartphone-based tests revealed some significant performance limitations of the Verizon network when we connected to it with a Motorola Droid.

In our winter tests involving 280 testing locations in 13 cities, the Droid rarely approached Verizon's promised upload speed of 500 kbps. Overall, the Droid delivered an average upload speed of just 116 kbps, the lowest average of any carrier/phone combo in our smartphone tests. And in numerous tests using the Droid, we recorded upload speeds of less than 75 kbps — painfully slow if you’re trying to send data of any size up through the network.

We also had trouble establishing a reliable connection between the Verizon network and the Droid during our tests. Verizon delivered an uninterrupted signal at reasonable speed in only 76 percent of our tests — far below the success rates of the 90-plus percent that the other three carriers achieved.

Download speeds to the Droid, on the other hand, were quite good, at an average of 1,075 kbps; that's not far from the upper end of the speed range that Verizon promised its customers, and ranks as the second-highest average download speed in our smartphone-based tests — behind only AT&T. The Droid connected at near- or above-1,000 kbps speeds in every testing city but Phoenix, where it averaged just 696 kbps on the downlink.

Verizon says that PCWorld’s assessment of its 3G performance doesn’t tally with the results it sees in its own tests. Moreover, Verizon points out, speed isn’t everything. As in its controversial “there’s a map for that” commercials, Verizon likes to emphasize the breadth of its 3G coverage.

“Consistency, coverage, and reliability —the ability to make and keep connections, and perform the tasks they want to over our wireless network at 3G speeds in more places — is what sets Verizon Wireless apart,” says Verizon corporate communications director Thomas Pica in an e-mail message to PCWorld.

Verizon’s 3G network does indeed have easily the greatest coverage area of any network (the company says that it covers more than 90 percent of the United States). So Verizon can still brag about that.

Sprint continues dependable ways

During 2009, Sprint began to support millions of data-hungry Palm Pre and Android phones on its 3G network. Sprint says that 49 percent of the handsets it sold during the fourth quarter of 2009 were smartphones or other touch-screen devices, up from 41 percent from the quarter before. To accommodate the increased demand for wireless broadband that those devices bring, Sprint says that it spent $1.2 billion on its wireless network during 2009.

Overall, our research suggests that, in the areas we tested, those investments were just enough to enable the network to keep up with the increased demand.

Sprint’s network reliability scores suggest that customers aren’t having many problems getting on the network. Sprint ranked first in our reliability tests eight months ago, and it improved on that measure in our latest tests.

Last spring we obtained a solid connection to the Sprint network in 90.5 percent of our tests; that figure increased to 94 percent in our most recent tests. The network scored perfect reliability marks in Baltimore, Portland, and San Diego, meaning that we enjoyed solid, uninterrupted connections at all 20 testing locations in each of those cities.

The Sprint network isn’t as speedy as it is dependable, however. The network registered download speeds of 795 kbps on average across our 13 testing cities — virtually unchanged from the 808 kbps it averaged in our tests last spring.

Steady upload speeds

Upload speeds also remained steady: Sprint uploads averaged 396 kbps in our winter tests, up slightly from the average of 371 kbps average we recorded last spring. These speeds are well within the ranges that Sprint promises its customers — upload speeds of 350 to 500 kbps and download speeds of 600 to 1400 kbps.

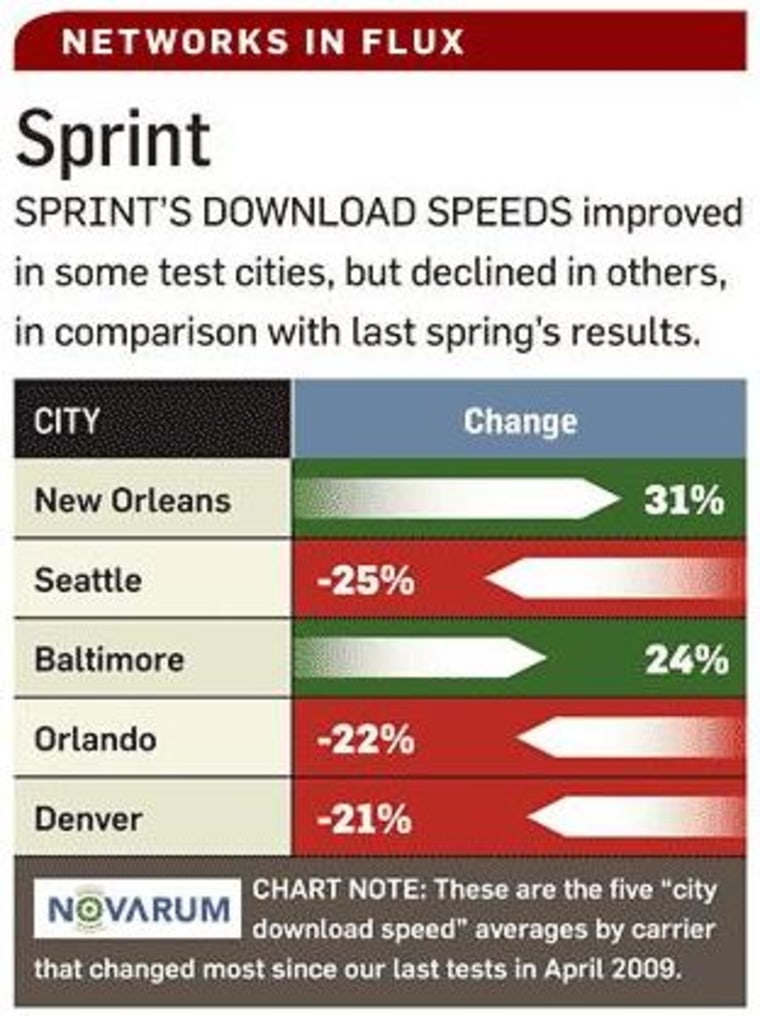

Sprint’s speed results suggest a tale of two kinds of cities — ones where the company upgraded its network in the past eight months, and ones where mobile broadband demand is outpacing any increase in capacity.

We saw speed increases of 20 percent or more in Baltimore, New Orleans, and San Diego; but in Denver, Orlando, and Seattle, average download speeds decreased by more than 20 percent in our tests. The net result: Sprint had the lowest average download speed across all our tests among the Big Four carriers.

One possible explanation, according to Novarum CTO Ken Biba, is that Sprint is expanding its service city by city, upgrading networks where mobile broadband demand is greatest. The cities where it hasn’t yet upgraded its network are dragging down its 13-city average speed in our test results.

Sprint says that it has added about 11,000 cell sites to its 3G network since 2006, but it won’t disclose how many of those sites debuted in the past year.

“As customer demand grows, we have to continue to upgrade our network on a cell site by cell site basis,” says Sprint networks vice president Bob Azzi. “I think we’ve been doing a good job of staying ahead of that growth.”

Testing the HTC Hero on Sprint

The speeds we saw in our smartphone-based tests of the Sprint network (using an HTC Hero) seem to corroborate Azzi’s claim: Though the capacity of Sprint’s network may vary from city to city, the performance that smartphone users see on the ground is fairly consistent across all 13 of our 13 testing cities.

Download speeds for the Sprint/Hero combo consistently fell within the range of 700 kbps to 1,000 kbps in most testing cities, yielding an overall download speed average of 851 kbps —significantly slower than the average connection speeds of 1,000 kbps or better achieved by the AT&T/iPhone and Verizon/Droid combos. Sprint delivered download speeds in excess of 1,000 kbps to the Hero in just 30 percent of our testing locations.

Upload speeds, while not impressive, were again consistent. We recorded upload speeds in the range of 100 kbps to 200 kbps — for an average of 145 kbps — across the Sprint network; those figures are in line with the uplink performance of the other phones in our study.

As for reliability, Sprint established a solid connection with the Hero in 92 percent of our tests, the second-best reliability score in our smartphone-based tests.

Azzi says his company has seen a “double-digit” growth in mobile broadband usage via devices like the Hero over the past year, but he welcomes the increasing demand.

“We want people to use as much data as they want, to use it in any way they want to use it; and we want make sure they can use any apps that they want to use,” Azzi says. “My job is to stay just ahead of that.”

T-Mobile: Playing With the big boys

In our tests, T-Mobile’s 3G network delivered download speeds that matched Verizon’s and Sprint’s, and it clocked surprisingly fast speeds in New York City. Averaged across our 13 testing cities, the T-Mobile 3G network showed an average download speed of 868 kbps — very close to Verizon’s average speed of 877 kbps — and delivered an average upload speed of 311 kbps. T-Mobile tells its subscribers that they can expect upload speeds in the “hundreds of kbps” and download speeds of up to 1 mbps.

T-Mobile clocked its fastest average download speeds in Chicago (1,047 kbps), Phoenix (1,201 kbps), Portland (1,090 kbps), and New York City (1,220 kbps). During one of our 1-minute speed tests in Manhattan, the T-Mobile network turned in an average download speed of 3 mbps, and registered burst speeds of up to 3.5 mbps. Speeds in the vicinity of 3 mbps are typically seen only in 4G networks.

T-Mobile’s network didn’t perform as well in other cities where we tested. The network reached its performance nadir in New Orleans, where we measured an average download speed of 570 kbps and an average upload speed of 181 kbps. Transfer speeds were so slow in tests conducted in the northern part of the city that the network was virtually unusable, according to Novarum’s Biba, who performed the tests.

Testing the HTC G1 on T-Mobile

In our smartphone-based tests, T-Mobile’s network connected with the HTC G1 reliably, but it didn’t support especially fast connection speeds to the device. We successfully established a solid connection with the T-Mobile/G1 combo in 93 percent of our attempts — the best reliability score of the four carrier/smartphone combos in our tests.

But the T-Mobile network delivered an average download speed to the G1 of only 719 kbps in our 13 testing cities — the slowest average in our smartphone test — and it connected at speeds exceeding 1,000 kbps at only 13 percent of our testing locations. Upload speeds were lackluster, too: The G1 posted an average upload speed of 134 kbps in our tests, the second lowest average in our smartphone study.

T-Mobile was the first carrier in the United States to support new Android phones like the G1, and it is the only 3G network available for the high-profile HTC/Google Nexus One.

As Android phones continue to gain mainstream popularity, T-Mobile’s network will have to support more and more wireless data use. T-Mobile says that monthly demand for mobile its broadband increased by 275 percent during 2009. At last report (October 2009), T-Mobile had 2.8 million 3G smartphones connected to its network.

Compared to A&T and Verizon, T-Mobile’s wireless business is small, but the reach of its 3G network grew rapidly in 2009. At the beginning of that year, about 100 million people lived in areas where T-Mobile provides 3G service; today, the network is available to more than 200 million people in 271 U.S. cities, the company says. In January, T-Mobile announced that, like AT&T, it had finished converting its 3G network to the faster HSPA 7.2 technology, as promised.

The 3G network may be growing fast, but T-Mobile’s subscriber count seems to be increasing at a more leisurely pace. The company reported that it 33.4 million wireless subscribers at the end of the third quarter of 2009, up marginally from the 32.8 million it reported at the end of 2008.

Upgrading the cell sites

When wireless carriers upgrade their networks in a particular market, what do they actually do? Usually the improvement isn't a matter of erecting more cell towers, a process that can be expensive and fraught with bureaucratic hassles with local government.

Often, wireless carriers focus on upgrading the software at their cell sites to increase speed and capacity. This is what AT&T did when it recently upgraded its cell sites from HSPA 3.6 technology to HSPA 7.2 technology.

The wireless carrier may also add capacity to an existing cell site by adding a new frequency band to the wireless spectrum already available for its subscribers to use in that cell zone.

When Sprint and Verizon added a new frequency band added to their cell sites, the sites theoretically gained 9.3 mbps in download speed and 5.4 mbps in upload speed. (After an upgrade, the actual speed that a wireless device can achieve depends on its distance from the cell tower, the number of other wireless subscribers using the cell, and the complex wireless protocols baked into the device itself — which determine its maximum connection speed.)

The same procedure is used by AT&T and T-Mobile engineers when they add a new frequency to cell sites in their GSM networks. These networks add three GSM radios to transmit and receive on the newly allocated slice of wireless spectrum. For the newest variation of the GSM data standard — HSPA 7.2 — this upgrade adds 21.6 mbps of maximum download capacity and about 17 mbps of maximum upload capacity to the cell.

There is, however, one big difference in the way new bandwidth is added to CDMA and GSM towers, respectively. On Sprint and Verizon CDMA radios, voice and data services occupy separate frequency bands. Because the radio can communicate on only one band at a time, CDMA subscribers can’t carry on a voice call while surfing the Web.

In AT&T's and T-Mobile’s GSM networks, voice and data service run on the same frequency band, so the caller can talk on the phone and surf the Web simultaneously.

4G is coming fast

Consumers are getting used to the idea of a mobile, connected, on-demand world. As consumer expectations of wireless networks rise, carriers are in a position to make a lot of money at a high profit margin. All four of the Big Four carriers are feeling the pressure to increase the speed and capacity of their wireless networks to accommodate the bold new world that consumers want.

On key component of the emerging mix is a new generation of wireless network called 4G, and mobile operators are scrambling to start building such networks.

For Sprint, 4G means providing WiMax service via the Clearwire network, which now reaches 27 U.S. cities and is spreading to new cities rapidly.

This development puts Sprint well ahead of the other U.S. mobile operators in the move toward 4G. Sprint plans to release a number of dual-mode 3G/4G devices, including phones (the first of them this year), that will connect at superfast 4G speed when possible, and will fall back to a 3G connection when not.

For Verizon Wireless, 4G means adding an overlay network using LTE (Long Term Evolution) technology. New hybrid modems and phones will use the 4G LTE network for high-performance applications, but will continue using the existing 3G CDMA network for voice and in situations where 4G is unavailable.

Verizon says that it will launch its new LTE network in 25 to 30 markets in 2010, and it hopes to have 4G coverage for almost all of its current nationwide 3G footprint by the end of 2013.

T-Mobile is moving toward 4G by converting its network from HSPA (High Speed Packet Access) to HSPA+, which T-Mobile says can pump out maximum download speeds of 21 mbps.

T-Mobile has deployed HSPA+ in Philadelphia, where some users have reported obtaining download speeds of up to 19 mbps. The carrier says that it will continue to build out its HSPA+ network this year, achieving a “broad national deployment” during 2010.

AT&T says that it will use its new HSPA 7.2 technology to bridge its current GSM/UMTS mobile platform to its LTE future. AT&T plans to commence field trials of its LTE technology later this year, and then begin switching on commercially available LTE networks in 2011. If the speed of AT&T’s recent upgrades is any guide, however, the company’s LTE launch may happen sooner than expected.

How we do the testing

For our tests, we chose cities that broadly represent the population density, socioeconomic statuses, physical terrain, foliage, and building construction found in medium to large U.S. cities. Our testing cities include Baltimore, Boston, Chicago, Denver, New Orleans, New York City, Orlando, Phoenix, Portland, San Diego, San Francisco, San Jose, and Seattle.

In each city we tested from 20 locations situated in a grid over the center of the city. These locations are roughly 2 miles apart, allowing us to measure service levels among and between numerous cell towers. Overall, we performed more than 51,000 tests in December 2009 and January 2010.

At each testing location, we subjected the networks to industry-standard network stress testing using laptops and to Internet-based testing using smartphones.

Our laptop-based tests use a direct TCP connection to the network to test the network's capacity — that is, the speed and performance that the network is capable of delivering to subscribers. Using the Ixia Chariot 4.2 testing tool running on a laptop PC, we tested both the speed and the reliability of the network.

To measure download speed, Chariot requests a number of large, uncompressible files from a dedicated server in the network; it then measures the speed of each transfer during a 1-minute period.

To measure upload speed, Chariot sends a number of files from the Chariot client on the laptop to the server on the network, again timing each transfer during a 1-minute period. We report the average of all of these transfers at each location as the location average. Then we average all tested locations to obtain an average city performance.

Reliability scores

We also assign a reliability score to each test. If during a test our client device cannot connect to the network, or if the network drops the connection, or if the throughput speed is unacceptably slow (less than 75 kbps), we label that testing location “low quality.”

We then report the percentage of testing locations in a given city that are of good quality. Thus, if we successfully establish an uninterrupted connection of reasonable speed at 19 of our 20 testing locations for a given network, we award that network a reliability score of 95 percent for that city.

Our smartphone-based tests approximate the real-world connection between specific smartphones and specific networks. We perform the smartphone tests from the same locations that we use for the laptop tests, applying an Internet-based performance test designed by Xtreme Labs.

The test sends a large test file back and forth between the smartphone and a network server, and then measures the speeds at which the data is transferred. We perform three upload tests and three download tests at each testing location.

We tested all 13 cities during December 2009 and January 2010, using the same locations, methodology, and personnel we used to test those cities in our April 2009 tests. Maintaining a consistent methodology allowed us to compare the performance of the networks across an interval of eight months and look for possible evolutionary changes.

We did not exhaustively survey every city. We tested from stationary locations only (no drive tests); we did not survey indoor performance; and we did not measure voice service.

Consider the network

U.S. consumers pay a lot for the convenience of mobile communications and computing. In 2009, Americans spent about $4.8 billion on wireless devices and service, and analysts project that they will spend an even bigger chunk of their paychecks on wireless during 2010.

Regardless of the type of connected device you use, you’ll eventually pay more for the wireless service that connects the device than you will for the device itself. So deciding on a wireless provider is a big decision — and an unwise choice can be a costly mistake.

We hope that our latest study arms you with some real-world information to help you pick the wireless carrier that’s best for you.