Huguette Clark was already a mystery. Now there are new glimpses into the life of the reclusive heiress.

The daughter of a disgraced former U.S. senator, Huguette inherited millions from the Montana copper mines, and has lived a solitary life while her three fabulous homes sit empty: a $100 million estate on the Pacific Coast in Santa Barbara, a $24 million country house in Connecticut and a $100 million co-op, the largest apartment on Fifth Avenue overlooking Central Park — all immaculately kept but unoccupied for decades.

As Huguette has just marked her 104th birthday in an ordinary hospital room in New York, there are unanswered questions as well:

Who protects an old lady who secluded herself from the world, limiting her life to a single room, playing dress-up with her dolls and watching cartoons? Who protects an old lady whose Stradivarius violin, the famous one called "The Virgin," which her mother gave her as a 50th birthday present, has been sold secretly for $6 million? Who protects an old lady whose dearest friend, a social secretary to whom Huguette supposedly gave $10 million, now has Alzheimer's and is unable to visit anymore? Who protects an old lady who has no children, and whose distant relatives have been prevented from visiting her? Who protects an old lady whose accountant fell behind on his own federal income taxes and is a convicted felon and a registered sex offender?

Interest in Huguette Clark was sparked in February by msnbc.com's photo narrative, "The Clarks: An American story of wealth, scandal and mystery." The story was one of the most popular ever on msnbc.com. Yahoo! Buzz named Huguette Clark a hot topic of Web searches. “The TODAY Show” followed up with a report and newly discovered photos of Huguette. The New York Daily News breathlessly declared, based on the Today report, "Reclusive 104-year-old heiress Huguette Clark enters hospital," which is true enough, though that event happened at least two decades ago. The tabloid also compared her to Paris Hilton, which will be an apt comparison if Miss Hilton doesn't have her photograph taken in the next 80 years.

But off the public stage, quietly we began to hear from people who have known Huguette through the years. Pieces of her story emerged. Here is an account of what we know about her decades of seclusion, and about the men who are watching her money.

Do you think she's still alive?

First, an update on those empty mansions:

In Santa Barbara, at Huguette's cliffside home known as Bellosguardo, or "beautiful view," estate manager John Douglas won't give the time of day, under the orders of Huguette's attorney, Wallace "Wally" Bock. But Douglas did tell his volleyball-playing buddies a story. The caretakers at Bellosguardo used to get long, handwritten notes from Huguette in New York City, giving instructions for upkeep of the 21,666-square-foot house on 23 acres, the labyrinthine rose garden, the dining room paneling from Sherwood Forest, the English thatched roof on the playhouse kept as a memorial to her sister, Andrée, who died at 16.

Bellosguardo is not for sale — an offer of $100 million was rejected. Huguette has not visited in at least 50 years. Then, years ago, Douglas got a phone call from an attorney — Miss Clark wanted to see him, to give him instructions personally. So he flew to New York, stayed in a nice hotel, and the next morning went to her apartment. He was allowed up in the elevator to the eighth floor, and into the great apartment's art gallery, 47 feet by 19 feet, with paintings by Old Masters and Impressionists. He sat for a while. Then a servant came to say that she was quite sorry, but Miss Clark didn't need to see him after all. He went back to Santa Barbara, and still hasn't met his employer.

Huguette's Connecticut country house in New Canaan, Le Beau Château, is out of view at the end of a long driveway that curls through woods. There's no intercom or bell, but one can rap on the air conditioning unit of a caretaker house by the gate. Tony Ruggiero, an 81-year-old former boxer, answers the knock but won't open the gate — attorney Bock has given strict instructions. Huguette bought this "country house" in 1952 and added a bedroom suite with an artist's loft — one can see the tiny paintbrushes carved into the handrails — but she never moved in. The 12,766-square-foot house with 52 acres is on the market for $24 million. The attorney and accountant keep the bills paid, including $161,000 a year for property taxes. Only one car is parked in the garages — Ruggiero's 1987 Jaguar. Ruggiero doesn't have answers, but he does have a question about the woman he has served for 21 years: Do you think she's still alive?

At 907 Fifth Ave., Huguette's New York apartment building overlooking Central Park, no one has seen her in at least 22 years. Other residents say she's been in the hospital for that long. Even before that, sightings were scarce. A housekeeper comes regularly to dust the 42 rooms, and attorney Bock occasionally counts the paintings. She has the entire 8th floor — 10,000 square feet — and half that much again on the 12th, her mother's old apartment, which is stuffed with dollhouses and fine furniture. Huguette's share of the building's taxes and upkeep is $28,500 a month, or $342,000 a year. Outside her door on the 8th floor, where the buzzer is unanswered, the building's staff has stored old carpets in the hallway.

Beginnings

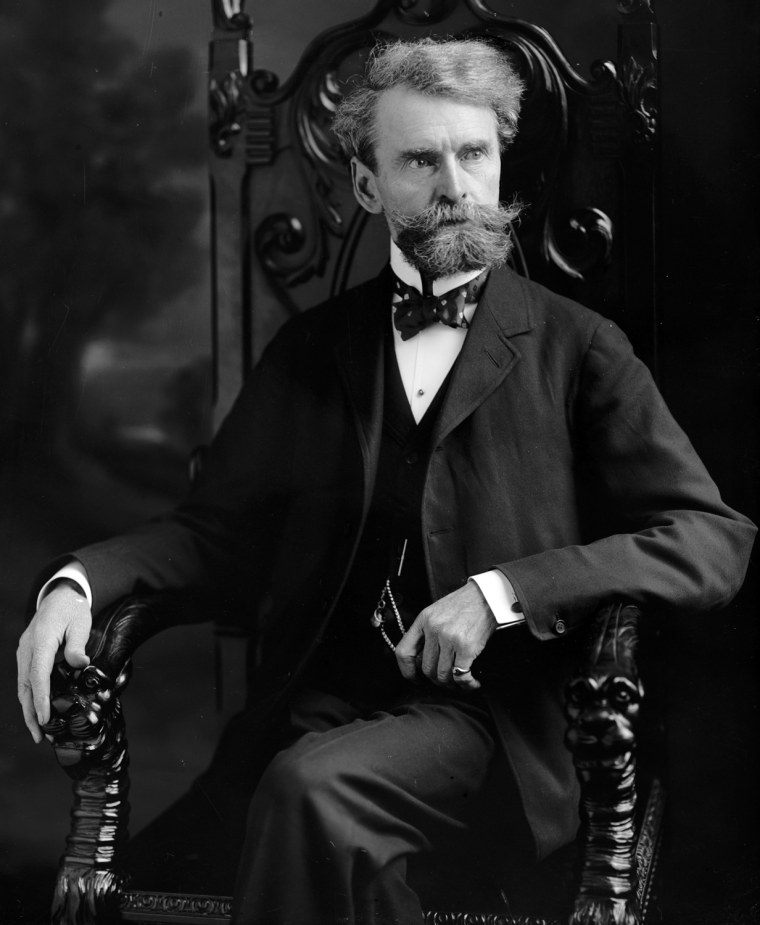

In Montana, where Sen. William Andrews Clark made his fortune and lost his reputation, people had assumed that all his children were long dead. After all, he was born in 1839, and was of age to serve in the Civil War. Instead, he headed west from Pennsylvania to the mines and became as rich as Rockefeller. His name was tainted by a colorful battle to see which Democrat could pay legislators the highest price for a seat in the Senate. His legacy includes the 17th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which switched to election of senators by the people.

The senator's reputation in Montana is summed up by Keith Edgerton, a professor of history at Montana State University-Billings, who is working on a biography:

"The cumulative sentiment here is that he made a fortune off of the state’s resources in the free-wheeling laissez-faire times of the late nineteenth century, prostituted the political system with his wealth and power, exploited the working class for his own gain, left an environmental wreck behind and took his millions to other places to benefit a handful of others. And in some ways, the state has never really recovered from it all."

Who would have thought that a daughter of the dour senator's second marriage, born in 1906 when the 67-year-old's red whiskers had turned white and he was mostly deaf, would still be alive 171 years after his birth? When our story appeared in February, the governor of Montana responded by writing to Huguette through her attorney, asking her to send some of her father's wealth back to the state for cultural institutions; he received no reply.

We don't know why Huguette became a recluse. Was it the grief from the death of her sister, Andrée, from meningitis in 1919? Was it the embarrassment of her divorce in 1930? Or the mortification of being named as a potential bride of a bankrupt rogue Irish duke in 1931? Was it the 1941 tell-all book by a former employee of the family, William D. Mangam's "The Clarks: An American Phenomenon," which questioned whether Huguette was Sen. Clark’s daughter and claimed that she broke up her brief marriage by failing to consummate it? (The family tried to pulp all copies of the book, but at least one survived.) Or was it simply the death of her mother in 1963?

Anna Clark and her daughter Huguette took up residence in the Fifth Avenue apartment in 1927, taking the entire 12th floor, which had been marketed as "the finest apartment in the world." Anna Eugenia La Chappelle had been the teenage ward who became the mistress and then second wife of the widower U.S. senator, who hid her away in Paris. They supposedly married in 1901 in France, though it wasn't announced until 1904 and no record of the marriage has been produced. Anna was 23, younger than the four children from his first marriage, and William was 62, older than his mother-in-law. The couple had two daughters, Andrée in 1902 in Spain, and Huguette in Paris on June 9, 1906.

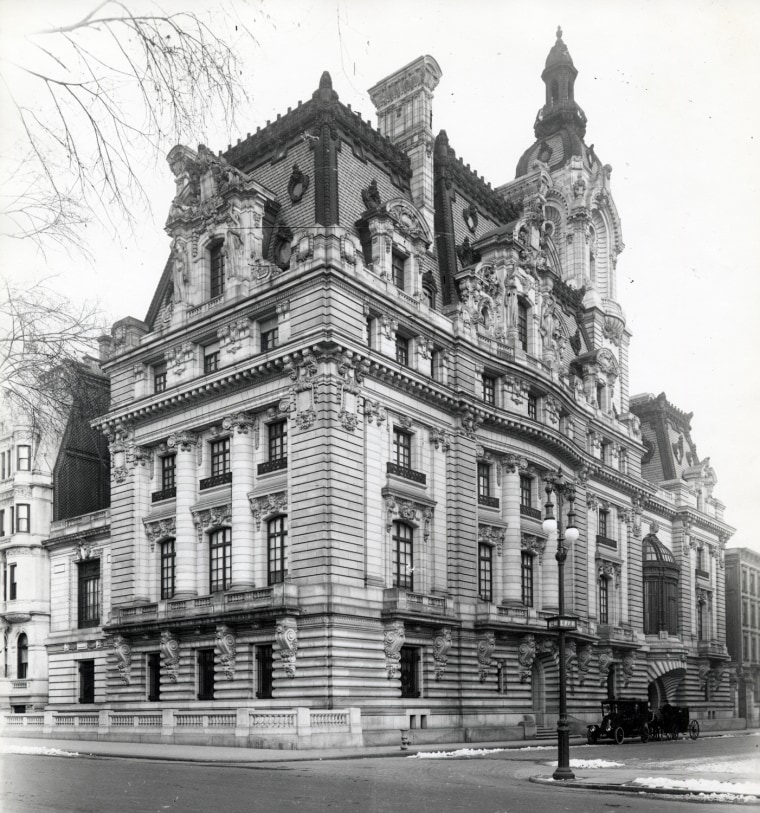

After he retired from the Senate, in 1907, William and Anna brought the children over to a grand mansion in New York, at 962 Fifth Ave., at 77th Street.

And what an overwhelming house for a young girl to grow up in. Her father's last will and testament describes the contents of its 121 rooms, including four art galleries with walls lined in velvet: 225 paintings, a statue of Eve by Rodin and others by Donatello and Canova, collections of antique lace, Greek and Egyptian antiquities, Gothic tapestries, Persian carpets, an Empire Room and a Gothic room, the Louis XV and Louis XVI salons, a circular Marble Hall, and antique bronzes representing Ulysses bending his bow and Prometheus attacked by the Eagle.

After the deaths of Andrée, in 1919, and William Andrews Clark in 1925, Anna and Huguette moved five blocks down Fifth Avenue, to the Italian-Renaissance apartment building at 72nd Street. The great house was sold and dismantled.

In New York they were active in society, the opera, parties with Huguette's friends from Miss Spence's School. Anna and Huguette also spent time in Santa Barbara, traveling on a private Pullman rail car.

"They weren't odd or strange," recalled Barbara Doran, who grew up at Bellosguardo, the daughter of a longtime estate manager. "They were very quiet, lovely, giving ladies. Huguette was the same age as my mother. They were always thoughtful about thinking of us, always making sure we were taken care of. My mother told me that during World War II, America was going to be invaded, we had coast watchers, and the Clarks had gold stashed in the basement of the big house. If we were invaded, we were told we were to go to the basement and get that gold, for all of us."

When Huguette married law student William Gower in 1928, the couple moved into the Fifth Avenue building, in a separate apartment from her mother. The Gowers had no children. After the divorce, in 1930, it was just mother and daughter. By the 1950s, they stopped going to Bellosguardo. Then Anna died in 1963.

What did Huguette make of her inheritance, her advantages? We have a few windows into her half century of seclusion.

The caretaker

One of Huguette's caretakers on Fifth Avenue for many years was an Irish immigrant named Delia Healey, six years older than Huguette. Healey worked for Huguette from the mid-1960s until just before Healey's death in 1980.

During one period back in the 1970s, Healey's grandchildren recalled, her main duties were threefold:

She would make Huguette's lunch every day, usually crackers with sardines from a can.

She would look after Huguette's impressive collection of French dolls, carefully washing and ironing their clothes. Healey ran out to buy new baby dolls as soon as they became available at FAO Schwarz.

She managed the recording of TV shows for Huguette to watch. Huguette purchased a newfangled Sony recorder and had it delivered to Healey's apartment. During one period, granddaughter Chris MacKenzie said, her grandmother not only had to record, but also to transcribe, every word of every episode of "The Flintstones."

Yabba-dabba-do!

Healey's grandchildren recall that she loved Huguette, and that Huguette sent them generous gifts in the 1970s: basketballs for the boys, the new Pong video game, an enormous dollhouse. "It had to be 2 or 3 feet tall, and the front of it swung open, hinged, and it was all hand-painted with flower boxes,” said Eileen Rowland, a granddaughter who lived with Healey. “It had two floors inside. The house was fully furnished. The little toilets had wooden toilet seats on them and the seats would lift up. She'd sent little dolls she'd had made to resemble our family: my Mom, and us, a dog.”

When Healey became too infirm to make the trip by subway, Huguette would send her chauffeur to pick her up at her apartment in suburban Larchmont, N.Y. During all this time, the children thought that their grandmother was taking care of a much older woman. "Now we know she was younger than my Grandma," MacKenzie said.

The antiques man

In the New York suburbs from the 1970s through the 1980s, Ann Fabrizio remembers that the phone would ring at home during family dinners, and a small voice with a French accent would ask for her father, the antiques dealer Robert Samuels of French & Co. Huguette would call almost daily with urgent requests — an inlaid table that had cracked, a chair to be reupholstered, new cases for the dolls. Samuels would head into the city from Crestwood, in Yonkers, a 35-minute ride on the train, then uptown to her apartment.

In 25 years, he never talked face to face with her. He saw only a shadow behind the door.

"Dad, being a patient man, would listen to her childish conversation — she from behind a closed door telling him that something in 'Mommy's apartment' needed work," Fabrizio said, though Huguette's mother, Anna, had died back in 1963. "I do remember that Dad would talk to her like a child. She wanted everything kept like Mommy had it, and that was not always possible.”

Samuels told his family that Huguette hadn't left the building voluntarily for a long time. She had a vintage car that had not been driven in 30 years, since her chauffeur died. "Dad tried to persuade her to sell it, but she would not hear of it."

"Several times, she had to be taken to the hospital for malnourishment," Fabrizio recalled her father saying. "One time the help could not get her to eat anything except bananas and ice cream."

As with the caretaker's children, Huguette would send gifts at Christmas, elaborate toy soldiers and forts, luxurious dolls, always from the Parisian store Au Nain Bleu.

"Even after my father retired, he continued to keep Miss Clark as a client, and he would trudge into New York City at age 80 to go to her empty apartment to check something out that she had called about," Fabrizio said. "He died in 2005 at age 90."

"By then she was living in the hospital. First she took up residence in Doctors' Hospital," on the Upper East Side, Fabrizio said. That hospital was razed in 2004.

"She had all her dolls over there. It was a safe environment for her."

The harpist

Anna and Huguette did have a regular visitor at the Fifth Avenue apartment from perhaps the 1940s until the late 1960s, one who brought music and memories of Paris.

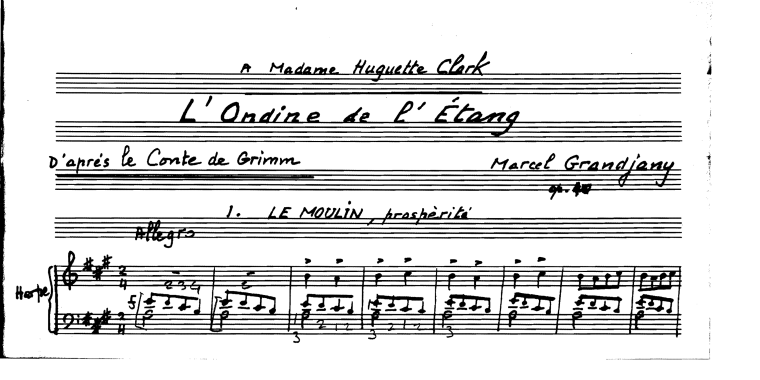

Huguette's mother, Anna, had studied the harp in Paris under the sponsorship of her husband-to-be, and by the 1950s she was a patron of a renowned harpist and composer, Marcel Grandjany, a Frenchman who began teaching in the 1930s at the Juilliard School in New York. Grandjany’s son, Bernard, now retired and living in Queens, still remembers the Clark address, 907 Fifth Ave., because he would drive his father over for lessons. "She never came to our house at all."

Grandjany's protégé, Kathleen Bride, a harp professor at the Eastman School of Music, recalled that in the 1960s Grandjany's wife would remind him that it was time to go over to "Mrs. Clark's" for a 4 o'clock lesson.

Among Grandjany's original sheet music, Bride found several unpublished and unrecorded manuscripts written between 1951 and the early 1960s, dedicated to a patron, "Madame W.A. Clark."

Other works are dedicated to Huguette. These works are dating from 1960, 1961 and 1968, indicating that she maintained the connection after her mother died. Anna's will left $100,000 to Juilliard. The lessons would have ended by 1970, when Grandjany was injured in a fall; he died in 1975.

The works for Huguette all have themes of childhood, though she was now middle aged, including a suite based on "La Belle au bois dormant," or "Sleeping Beauty." Also in her name is a larger work for the harp based on a Grimm fairy tale, as well as French folk songs.

Huguette's instrument was the violin. It appears that these harp lessons, one of the few contacts between the Clarks and the outside world, were for her mother.

"I have the feeling that these folk songs were used as teaching pieces for her to work on and then play at lessons," Bride suggests. "They may be tunes that she heard while in Paris."

The companion

The only friend known to visit Huguette regularly in her later years at the apartment, through the 1970s and 1980s, was Madame Pierre. Suzanne Pierre was the wife of Huguette's physician, Jules Pierre. Like Huguette, the Pierres were from Paris.

Suzanne was more than a friend to Huguette. She was also a sort of social secretary. She would carry messages and documents to the accountant and attorney. She helped Huguette dispose of paintings and other items anonymously. At the end of each year, Huguette would pay her a bonus.

Now Suzanne Pierre is a widow, at age 89 still in her Park Avenue apartment. I called on her without an appointment, on a stormy Saturday afternoon in March. I was told to come back in one hour, and she was ready, smartly dressed, with makeup on. Her caretaker had set out hot tea and cookies. We sat and talked in front of the television.

Yes, she said, she was Huguette's friend, a companion, but "her closest companions have always been her dolls."

She said she couldn't explain why Huguette was a recluse. "I would ask her to go out to lunch, but she preferred to stay in."

Huguette didn't trust outsiders, even relatives, because she "thought they were just after her money. She didn't trust people."

Suzanne was easily distracted by the television, and the conversation lagged. I showed her photos of Huguette, and her face brightened. She wouldn't divulge where Huguette was. No, she said, she couldn't recall the last time she had been to visit her.

In the kitchen, her caretaker explained that Suzanne has Alzheimer's disease, as Suzanne's son later confirmed.

A cousin of Suzanne's filled in the details. "From what I was told, one of the chief reasons that Ms. Clark trusted my cousin was that she preferred to conduct all of her conversations in French, so that others within earshot would be unlikely to understand the discussion," said Kurt Harjung, whose mother, Alice, talked with Suzanne Pierre nearly every day until Alice's death last year. "The whereabouts of Miss Clark was kept a secret, but she has been cared for in a private room with 24/7 staff and basically limited access by only my cousin and possibly her attorney."

Why was Huguette in the hospital? What kind of illness would justify staying in a hospital for 22 years?

"She just liked the comfort, she felt safe, she was isolated from getting sick and dying," Harjung said. "She was afraid of getting sick. She did not want to socialize with people for whatever reason."

Physically, "there didn't seem to be anything wrong with her. She was just a quirky person who couldn't contend with the outside world."

"Suzanne felt kind of sorry for her, in a way, because she didn't have any other friends, sequestered in a hospital room," Harjung said. "She had all this money and all these capabilities and never used any of them. This was her comfort zone."

And did you know, Harjung added casually, that Huguette gave Suzanne $10 million?

In 2000, "Suzanne mentioned that Miss Clark had given her — it wasn't clear whether it was a gift or given her to dispose of — a Monet or a prominent painting, the painting was valued between 10 and 15 million dollars, to market anonymously."

The gift is recorded, in an oblique way, in a federal tax case. Suzanne Pierre gave most of the money to her son and granddaughter, and the IRS challenged the amount of gift tax she owed. The court record explains that Suzanne "received a $10 million cash gift from a wealthy friend in 2000." (She won the tax case, too.)

I spoke briefly with Suzanne's son, Jacques "Jackie" Despretz, a maître d' at French restaurants. He did not dispute that Huguette gave his mother the $10 million, but offered no details.

As for his mother's contacts with Huguette, he said, it's been "a while," because of Madame Pierre's illness.

'There is no one'

Distant relatives had only irregular contact with Huguette by telephone.

André Baeyens, a retired French diplomat in Austria who wrote a book about the family, is Huguette's great-half-nephew, descended from Clark's first marriage. Baeyens spoke with Huguette on the phone several times, but found that she would back off when he pressed too hard for information on her father or herself. And then some years ago, she stopped taking his calls.

Other relatives have sought permission to visit over the years, and her attorney, Bock, has turned them away. He has told relatives that he passes along their messages.

Baeyens said that one of the great-great-half-nieces on the Clark side, Carla Hall, went so far as to go to the hospital room, about two years ago. "I know Carla forced things — went straight up and she saw Huguette. She was kept away."

Hall, an interior designer in New York City, said Huguette was asleep. "I visited the hospital, and met discreetly and quietly with Ms. Clark's nurse outside her room," she said in an e-mail. "On behalf of her family, I asked if I could enter the room and see her, though she was asleep. No one on the hospital staff nor her private nurse had any objection to my visit or entry to her room as they knew that I was a concerned family member. My intention was to assure the family that she was comfortable and receiving good care."

If Suzanne Pierre no longer visits, and no family visit, then who does?

"The only people she sees are people who are her attorney's people," Baeyens said. "Now if Madame Pierre is no longer seeing her, then it's finished.

"There is no one from the outside who is coming to see her."

ON TO PART TWO: Who is watching Huguette's millions?

---

More links for "The Clarks: An American story of wealth, scandal and mystery":

All our coverage is collected at http://clark.msnbc.com

A PDF file for printing the photos