Humans arrived at the International Space Station exactly 10 years ago, and the orbiting laboratory has not been empty since.

While crew members come and go, NASA and its international partners have been occupying the laboratory in the sky uninterrupted for a decade. The space station itself spent two years without a permanent crew before the first astronaut and cosmonauts arrived on Nov. 2, 2000.

"I think it's kind of incredible," said astronaut Peggy Whitson, chief of NASA's astronaut office at Houston's Johnson Space Center. "It's miraculous to have had people on orbit for 10 years continuously."

More than a dozen countries and space agencies from the United States, Russia, Europe, Canada and Japan have been building the $100 billion space station since 1998. Under NASA's new space plan, the station is expected to continue operating through 2020.

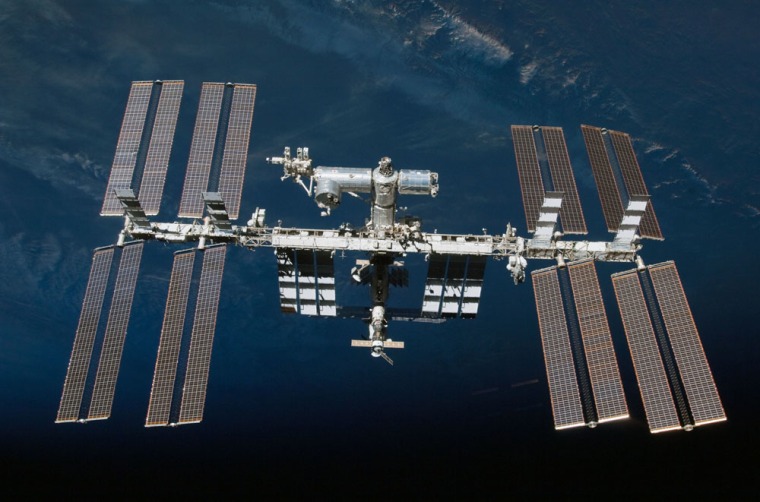

The space station, now about as long as an American football field and including about the same internal living space as a Boeing 747 jumbo jet, is practically complete.

NASA's space shuttle Discovery is poised to blast off on Wednesday to deliver the last major U.S. addition to the station — a windowless storage room — along with a humanoid robot called Robonaut 2. [Graphic: The International Space Station Inside and Out ]

Overcoming setbacks

Despite the enduring nature of the space station, there have been some setbacks — most notably from the devastating tragedy of the Columbia shuttle accident in 2003 and the subsequent 29-month grounding of the space shuttle fleet until flights resumed.

At the time, the space station's crew size was cut from three people to just two occupants — one American and the other Russian. Even during those lean times, the only time the station was left unoccupied was when crew members performed spacewalks outside the confines of the structure.

"We've overcome so much, and to know that we've kept the station permanently occupied that whole time, to me makes us a spacefaring civilization," NASA's deputy administrator, Lori Garver, told Space.com. "I have also said I do not feel I will have been a success at this job if there are days ahead where we do not have people living and working in space. So 10 years is a good start — we need to keep it running."

The Columbia disaster slowed down the pace of space station construction because the shuttles were the only vehicles capable of carrying up some of the outpost's larger components. The shuttle fleet returned to flight status in 2005, with station construction resuming in 2006.

Now, four years later, the orbiting lab is nearly complete. [Gallery: Building the International Space Station]

"Visually it's just stunning," said astronaut Tom Jones, who visited the first station's crew - called Expedition 1 during the STS-98 shuttle flight in 2001. "If I look at my snapshots from 10 years ago on STS-98 and then you look at what's up there today, it's just incredible growth in that facility."

As of Nov. 2, the space station has completed 57,361 total orbits around the Earth with humans onboard, said NASA space station flight director Royce Renfrew. The lab circles about 220 miles (354 kilometers) above the Earth's surface.

Expedition 1

The first expedition of astronauts to live at the International Space Station arrived Nov. 2, 2000 aboard a Russian Soyuz capsule that had launched Oct. 31, 2000, from Kazakhstan's Baikonur Cosmodrome.

Three spacefliers were aboard: American commander William Shepherd of NASA and flight engineers Sergei Krikalev and Yuri Gidzenko of Russia's Federal Space Agency. They stayed onboard for a total 136 days, or a little more than four months.

Astronauts who have come since, such as Nicole Stott, who served on Expeditions 20 and 21 in 2009, expressed their gratitude to the pioneers who began the station program.

"It just was such a great starting point for all of us, who now get to experience this ginormous volume and still sharing in this spectacular international program that has made it such an international success," said Stott, who is returning to the station this week aboard Discovery.

Over the years since that first mission, space station living has changed quite a bit. While early crews had a rather spartan existence, spending almost all of their time keeping a fledgling station running, current crews can devote much more time to research, and take advantage of wider food and entertainment options and even choose among a variety of exercise equipment (such as the relatively new COLBERT treadmill) to stay in shape.

"One thing that I noticed over that time is both the quality of life in training and the quality of life onboard the space station has continued to improve," said NASA astronaut Tim Kopra, who served for almost 60 days as a flight engineer for Expeditions 19 and 20 in 2009. "And that's a great thing. I think we're learning how to live in space. And every step and every crew is doing it better and getting smarter and the program is getting smarter."

Looking forward

Now that the space station is largely complete, crews living there can focus much more of their daily efforts on science research, rather than building the station's complex network of modules and tunnels.

In 2005, Congress designated the station a U.S. national laboratory, opening the outpost's U.S. science facilities up for use by non-NASA researchers. More than 400 scientific experiments in fields such as biology, human physiology, physical and materials science, and Earth and space science have been conducted there over the last decade.

Yet there is still a long way to go toward taking full advantage of the station for science, some say.

"What we havent done with the space station, I think, and which is a huge opportunity, is to use it as a test bed for going beyond," Jones said. "It should be the test bed for life support systems and communication gear and new generations of spacesuits — and even tiny self-propelled spacecraft that will allow us to explore an asteroid. Those should all be checked out, assembled and proven at the space station in the next 10 years."

There may be some growing pains ahead for the station when NASA's space shuttles retire, likely next year, and take with them their huge capacity for carrying large cargo to space. The space station will have to rely on Soyuz spacecraft, as well as unmanned European, Japanese, and possibly commercial cargo ships.

"It's going to be a little bumpy at first as we get used to not having that powerful cargo ship coming to the station, however, just like any other challenge we have faced at NASA we overcome it and we learn a whole lot from it," said NASA astronaut Tracy Caldwell Dyson, who recently returned from a six-month sojourn at the station as part of Expedition 24. "So I think we have a lot of good things to look forward to."

A new bill passed by Congress, and recently signed into law by President Obama, authorizes NASA to continue the space station program through at least 2020.

"I see the space station as just beginning," Whitson said. "I have hopes that we're not halfway through — we're less than halfway through."