Scientists say no antidote or vaccine can counter the poisonous effects of ricin ... yet. But as lawmakers and law-enforcement officials deal with this week's ricin scare on Capitol Hill, researchers are working on projects that could help defang the terror threat.

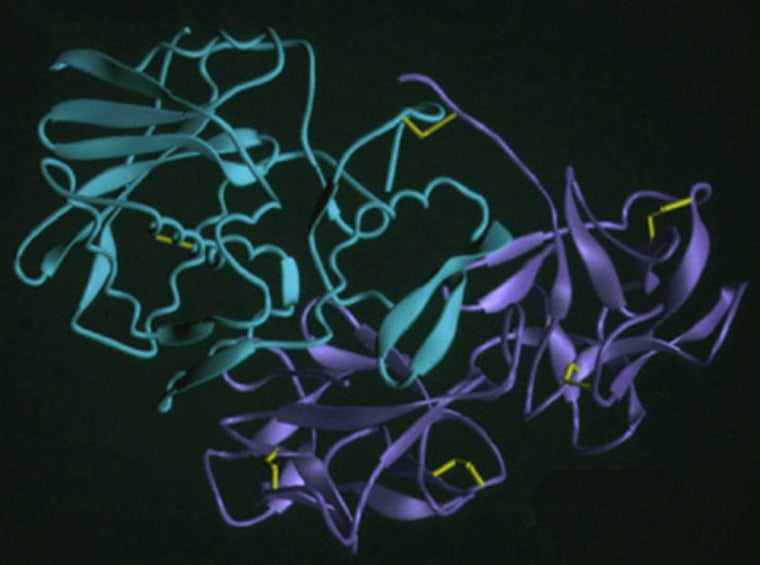

Ricin, which is derived from the castor bean, kills by disrupting the protein factories inside your cells, known as ribosomes.

For now, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention can recommend only that you stay away from the toxin, or flush it out in the event of exposure. Treatment addresses only the symptoms of ricin poisoning, such as respiratory problems, seizures or low blood pressure. In the end, it's up to your immune system to develop antibodies and destroy the ricin protein before it destroys you.

But if the Food and Drug Administration gives its go-ahead, one potential anti-ricin vaccine could begin clinical trials by the end of the summer, said Ellen Vitetta, director of the Cancer Immunobiology Center at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

The U.S. Army Medical Research Institute for Infectious Diseases is also working on methods to counter ricin's effect.

Meanwhile, Canada's military research agency is cooperating with two Canadian biotech companies to develop a ricin antidote that could be injected after exposure, just as antidotes are available today for rabies and snakebites.

"We think there's good hope to develop treatments for most of these bioterrorism products, whether it's using our technologies or some of the other technologies that are out there," John Langstaff, president and chief executive officer of Winnipeg-based Cangene Corp., told MSNBC.com.

No one is willing to say exactly when ricin will be tamed. But Thor Borgford, who is president of Twinstrand Therapeutics in Burnaby, British Columbia, believes an antidote will be available "certainly within the next five years, if not a lot sooner."

Ironically, ricin's cell-killing properties have long inspired spin-off drugs used in chemotherapy.

"We do not work with ricin per se," Borgford stressed. "We're developing treatments for cancer and other diseases. It happens that the molecules we're working with are similar to ricin, and we understand them very well. ... Our expertise lends itself to the development of antidotes in this area."

The technology for developing anti-ricin therapies could conceivably be used as well to develop kinder, gentler methods of anti-cancer chemotherapy.

Tweaking vaccines

The application to cancer treatment is a primary factor behind Vitetta's two decades of ricin research. Vitetta and her colleagues reported two years ago in the journal Vaccine that anticancer drugs could be tweaked to create a nontoxic vaccine against ricin.

"The vaccine is protective, it's safe, it protects mice very well," she said.

If the clinical trial goes forward, human volunteers would be injected with the vaccine, informally called CBTox. Then researchers would see whether the human subjects' blood contained antibodies to fight ricin. Those antibodies would be administered to lab mice. The mice would then be exposed to ricin to test their immunity.

"I hope that we will be able to complete the whole thing within about eight to 12 months," Vitetta said. If the trials are successful, the vaccine could be developed commercially by DOR BioPharma, she said.

Creating antidotes

In the Canadian project, Twinstrand is developing nontoxic chemicals that mimic ricin on the molecular level. "We do have a very clear indication that we're moving in the right direction," Borgford said.

The next phase would be up to Cangene. "If we can get a synthetic, nontoxic ricin, we would inject that into an animal — a goat or a horse — and then we would extract the antibodies and manufacture that," Langstaff said.

Defense Research and Development Canada, based in Suffield, Alberta, would be responsible for testing the effectiveness of the antibodies on animals, using actual ricin. "Our objective is to produce a commercially valuable asset, an antidote that would neutralize ricin," Borgford said.

Langstaff, whose company also is working on treatments for other potential bioterror agents such as anthrax and the Ebola and Marburg viruses, said there were good prospects for developing chemicals to resist ricin's effects. "But the problem with many of these is that timing may be an issue," he said.

He said an effective ricin antidote would have to work within hours, since that's how little time it takes for the poison to work.

Vitetta said the scientific fight against the ricin threat wasn't easy.

"It's dangerous, so you have to be very careful," she said. "It's hard to be involved, because you have to become a select-agent laboratory and you have to have funding, and you have to have a supply of ricin, and you have to have a lot of things that a lot of people don't have. The interest is there. It's just that the compliance and the work is quite tedious."