There’s a key scene in the documentary “Race to Nowhere” when a high school student asks, “If I can’t fail, and make mistakes, then how can I be expected to learn?”

Such a question might earn a stern slap on the wrist from “Tiger Mom” Amy Chua. But it’s an astute observation and one that drives home the main point of the film: that our preoccupation with testing and performance has undermined actual learning in the classroom, and may even be threatening the healthy development of kids, who frequently feel overwhelmed by the pressure to excel at all costs.

Since it was released in September, the small-budget, big-buzz doc has been shown in more than 1,400 community centers, schools and churches around the country, drawing audiences composed mostly of parents but including teachers and school administrators — many of whom are eager to share their anxieties about what students are sacrificing for the sake of academic success.

And while those problems may seem specific to a rather narrow, predominantly affluent demographic, it's significant that at a time when education is often referred to as the civil rights issue of our time, there are families seemingly best-served by the existing system who are questioning the status quo.

After hearing about “Race to Nowhere,” attorney Roger Medoff arranged for a screening at a community center in his hometown of Columbia, Md. He was relieved and surprised when more than 200 people showed up, many of them staying for the town hall-style discussion afterward.

“I thought it was really cool that this film was articulating issues that I’d been struggling with for a while,” he says. “It really confirmed for me that there are a lot of people who share my feelings.”

Before becoming a lawyer, Medoff taught middle school in the early 1970s. “The pendulum was in a very different place then — it was a very experimental time," he says. “That’s when I think I developed my values about what progressive education could be. So for a long time I have been critical of, and angry about, this culture of excessive testing and homework.”

As Medoff and several of the families profiled in the film admit, being in a constant state of measuring stems from an all-American allergy to being average — a fear that anything less than exceptional isn’t good enough. (A fear that Sarah Palin recently played upon when she accused President Obama of a "lack of faith in American exceptionalism.")

'We need to back up here'

When Amy Kappers’ eldest daughter, Olivia, a sophomore at Walnut High School in Cincinnati, scored in the 98th percentile on a practice PSAT exam, her mother was impressed — but Olivia was disappointed.

“I was like, OK, we need to back up here,” Kappers says.

When it came time for Olivia to choose her course schedule for her junior year, her mother argued for limiting the number of advanced-placement courses she could take — even though Olivia’s teachers were encouraging her to take more.

“It’s not that we don’t think she can handle it, it’s just that there’s a balance,” Kappers says. “We told her, if there’s a basketball game on a Tuesday night, you should be able to go.”

Her daughter saw things differently.

“I expected my mom’s reaction to some extent; I know she wants me to have some balance,” Olivia says. And while being on the cross-country running and track teams ensures that she’s not studying all the time, she admits she misses having more face time with friends. “There are some weeks when I feel like I didn’t really do anything, like I should have called someone,” she says.

Loading up on AP courses would mean even more homework next year, but Olivia felt pressure to take advantage of all that her school had to offer.

“It’s like, AP is something you strive to get into — if I’m not taking them, I feel like I wouldn’t be as challenged," she says. "In some ways I feel like taking it easy would actually do the opposite and make you stressed out that you’re falling behind, especially when it doesn’t look as good to colleges that your school offers 30 AP courses and you only take two.”

In the end, Olivia and her mother reached a compromise of four AP courses. Amy Kappers describes the experience as “eye-opening.”

“I told my husband, I don’t think there are a lot of families having these discussions. In most houses, it’s: ‘You need to study more, get better grades, buckle down,' " she says. “So it is a little awkward. I don’t have a lot of people I could talk to about this.”

Problems or privileges?

Before he became aware of the support around “Race to Nowhere,” Medoff assumed he was alone in his concerns as well.

“I imagine the kids profiled in “Waiting for Superman” wish they had these problems,” Medoff says. “I’ve thought about this a lot, and I understand that some would consider these issues to be privileges. But guess what? There’s a whole different set of problems on this side of it.”

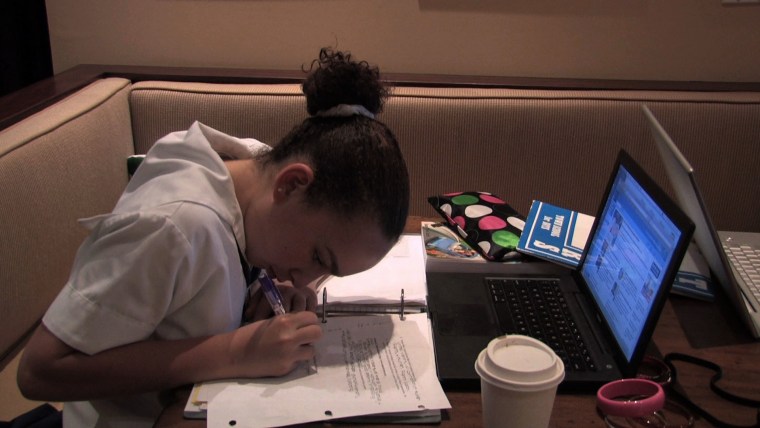

While Medoff speaks with pride about his eldest daughter, who at 18 is a self-motivated, high-achieving senior, he worries that those achievements come at too high a cost.

“She’s up late, she’s disorganized and stressed out," he says. "It just seems fundamentally unhealthy.”

But his daughter frequently defends her habits.

“She would argue, ‘This is what colleges want, this is what I need to do. It’s great that you’re on this bandwagon, but I have to go to school tomorrow and deal with this,’ ” Medoff said.

Whether the activism inspired by “Race to Nowhere” will result in meaningful change remains to be seen; but already at Medoff’s school, two teachers have adopted a no-homework policy since seeing the film. And Medoff's daughter has decided to attend a college that wasn't necessarily the most academically competitive, but one that felt like the right fit for her—one that's more supportive and nurturing of its students.

“There are little nips and tucks taking place, but I think just as importantly, this has given parents more confidence in putting their foot down," Medoff says. “Last night, for instance, I told my daughter that even if she wasn’t finished with her work by 9:30, she had to stop. Of course, it doesn’t always work. It’s still an uphill battle.”