The utility behind Japan's biggest nuclear plant disaster can't seem to get much right.

The obviously harried officials from Tokyo Electric Power Co. have repeatedly announced botched radiation readings, corrected themselves over and over and indulged in seemingly endless rounds of apologies.

Every few days, Japan's nuclear safety industry scolds them to "to take steps to prevent a recurrence of similar mistakes."

The bumbling offers alarming insight into the embarrassing failure of crisis management at the nation's top utility, which rakes in 5 trillion yen ($60 billion) in annual sales.

The officials have been doling out information piecemeal about the unfolding crisis at the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear plant, which erupted after backup generators — critical to powering the systems that cool the reactors — were destroyed by the March 11 tsunami, for which the company was sorely unprepared.

And the mistakes keep coming. Take Sunday, for instance.

In the morning, Tokyo Electric Power Co. told reporters that radiation levels in contaminated water in one of the troubled reactors at the plant had surged to 10 million times the level than when the reactor is working normally.

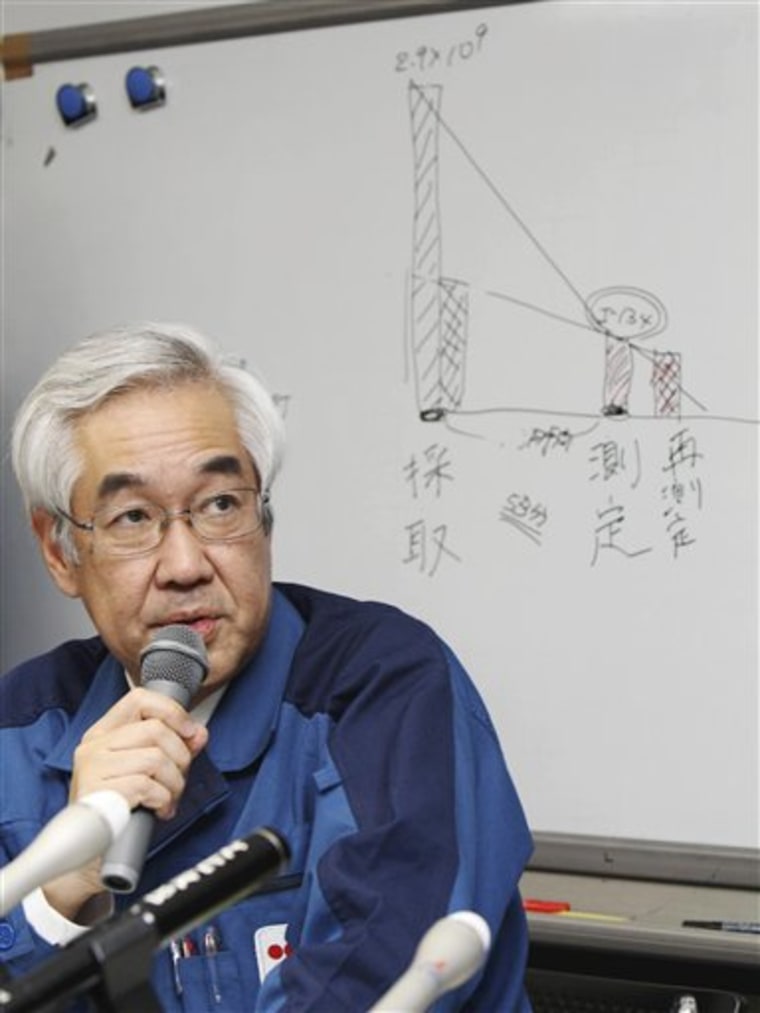

Eight hours later, TEPCO Vice President Sakae Muto bowed in apology. They had gotten it wrong, misreading a machine that analyzes water samples and mistaking one radioactive isotope for another.

The real number turned out to be 100,000 times normal — still high, but well below their terror-inducing earlier figure that caused an immediate evacuation of workers from the reactor.

"This sort of mistake is not something that can be forgiven," Chief Cabinet spokesman Yukio Edano said Monday.

Earlier Monday, TEPCO was forced to apologize again for naming the wrong isotope in its correction. It had gotten their isotopes wrong not just once, but twice.

If such errors seem dizzyingly technical to most of the world, they are basics for the nuclear power industry, where mistaking two isotopes is a major error.

Mitsuhiko Tanaka, a Fukushima nuclear plant designer turned anti-nuclear activist, said utility officials aren't fully equipped to orchestrate the response to the crisis. He says they aren't familiar enough with reactor designs, any more than pilots or stewardesses know the design of a jet engine. He urges more involvement of designers and other experts.

"When a jet begins to crash, you don't ask the pilots for answers to what's gone wrong," he said in an interview.

A few examples of TEPCO's missteps:

- For the first week after the tsunami, TEPCO radiation reports showed that hourly readings of airborne levels near the plant had were twice as high as recommended health levels. In fact, they had been off by one decimal point for dozens of readings for days. Radiation doses had actually exceeded the limit by 13 times.

- When three TEPCO workers were hospitalized after wading into radioactive water, the company gave their condition only as "unknown." Days later, the hospital and government officials reported the workers' conditions — but TEPCO still refused to say anything.

- TEPCO officials said two of those workers were injured after they were issued ankle-high protective boots to walk into highly radioactive knee-high water. The company has yet to explain how that happened.

When pressed for details, TEPCO officials often simply don't answer. They say they will check, insist an answer would disclose personal information or say they don't know.

Also baffling has been the obvious lack of coordination between TEPCO and its main government regulator, the Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency.

TEPCO and NISA give separate news conferences, often releasing conflicting information. At one point, NISA acknowledged the possibility of a partial meltdown in much stronger language than TEPCO officials, only to tone it down later.

Crisis management experts say it is critical to have a central crisis office to release consistent information to the public and the media to avoid raising fears and to coordinate information from the utility, government, regulators and local officials.

But in Japan, responsibility tends to be spread out, imperiling crisis management.

The 24-hour "media center" at TEPCO headquarters, with its crammed desks, disorganized handouts and lack of scheduled briefings, looks more like a sloppy classroom. Officials often give just a few minutes warning before they make announcements, sometimes long after midnight.

Adding to the uncertainty is TEPCO's troubled history of cover-ups and scandals.

The company has been repeatedly penalized by the government over the years for misbehavior that includes tampering with reports on plant safety.

Surrounded recently by worried reporters, TEPCO manager Hikaru Kuroda promised that the workers now tackling the crisis were fully in control.

"I may be losing my grip on things, but they aren't losing theirs," he said with a smile.