So we now have proof that it is possible to clone a human embryo -- sort of. Now what?

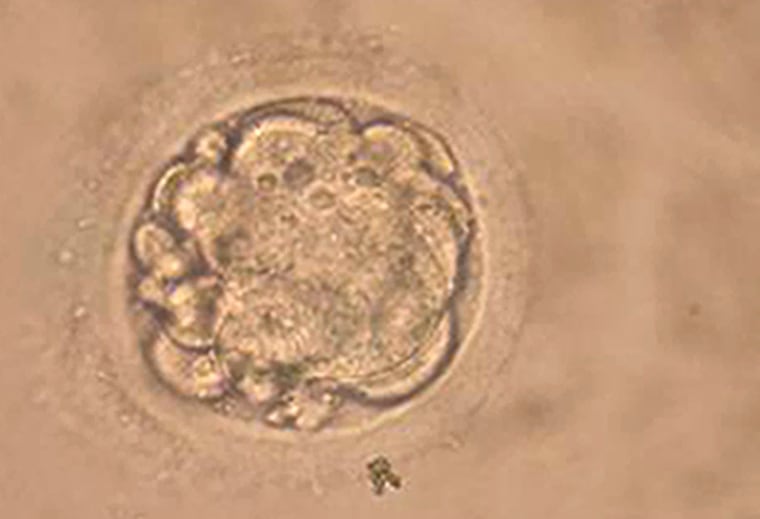

Korean scientists working with an American cloning expert from Michigan State University have reported in the peer-reviewed journal Science that they have cloned a human embryo using the same technique that created Dolly the sheep. Previous reports of human embryo cloning were issued by people wearing Starfleet Command uniforms, those who own companies whose stock was badly in need of a boost, or fringe scientists whom no one in the mainstream would trust to report anything honestly.

Still, the latest report is not quite the gold standard of proof that shows human cloning is possible. It is more like a silver standard.

Not just any old cell

This is because the kind of cell used as the source of transfer DNA, namely a cumulus cell, is a very odd cell that is poorly understood. Only women have cumulus cells and only fertile women have cumulus cells that work. This type of cell basically supports the viability of eggs in a woman’s body, a function that may make cloning using a cumulus cell easier to do.

While cloning from your own cumulus cell to your own egg, which is what the Korean group said it had done, is interesting, it is still the case that for any male or post-menopausal female to find a cure from cloned human embryos scientists will have to use DNA from skin or other tissues in the body. These cells may well prove much harder to clone than a cumulus cell.

U.S. brain drain?

The other interesting aspect of the latest cloning research is that it was carried out in South Korea. This is probably not just a function of the fact that good science is conducted by many people in many countries.

In this case, the American who helped the Korean group was there because he found the current atmosphere in the United States hostile to therapeutic cloning research, or cloning for the purposes of finding cures for diseases. He is not alone. Many American scientists are increasingly spending time overseas in countries such as Britain, India, Singapore and China because the Bush administration has forbidden human embryonic cloning research.

You and your tax dollars have supported a great deal of research on human genetics and biotechnology at the National Institutes of Health and other federal agencies. But what is the sense in developing a biotechnology research base that is the envy of the world only to see the world take what we have learned so that it can someday sell the research back to us?

Human cloning is controversial, but mainly for the wrong reasons. The topic is linked in many people’s minds to the cloning of people, or reproductive cloning, which no one except a nut would want to try given the high failure rates that plague efforts to clone animals.

Those who want to protect the rights of human embryos keep lumping reproductive cloning and therapeutic cloning together when they are completely different. Our failure to make these distinctions in our public policies means that some day not only will we see people trying to import drugs from Canada, but we may well have to watch them pay through the nose to get cures for Parkinson's, spinal cord injuries or diabetes from Korea, China, Britain or Singapore.

Arthur Caplan is director of the Center for Bioethics at the University of Pennsylvania.