So widely hyped was evangelist Harold Camping’s prophecy of imminent rapture that even isolated Iceland, pop. 318,000, was subject to the onslaught of advertisements — and accompanying news stories — of doomsday.

On the morning of Saturday, May 21, Icelandic news site Vísir.is didn’t waste any time posting a story: “The World is Still Here.” The 89-year-old Camping predicted that the world would begin to quake at 6 p.m., but the story cited reports that everything was just fine in New Zealand and Tonga, which would have been among the first of the doomsday victims.

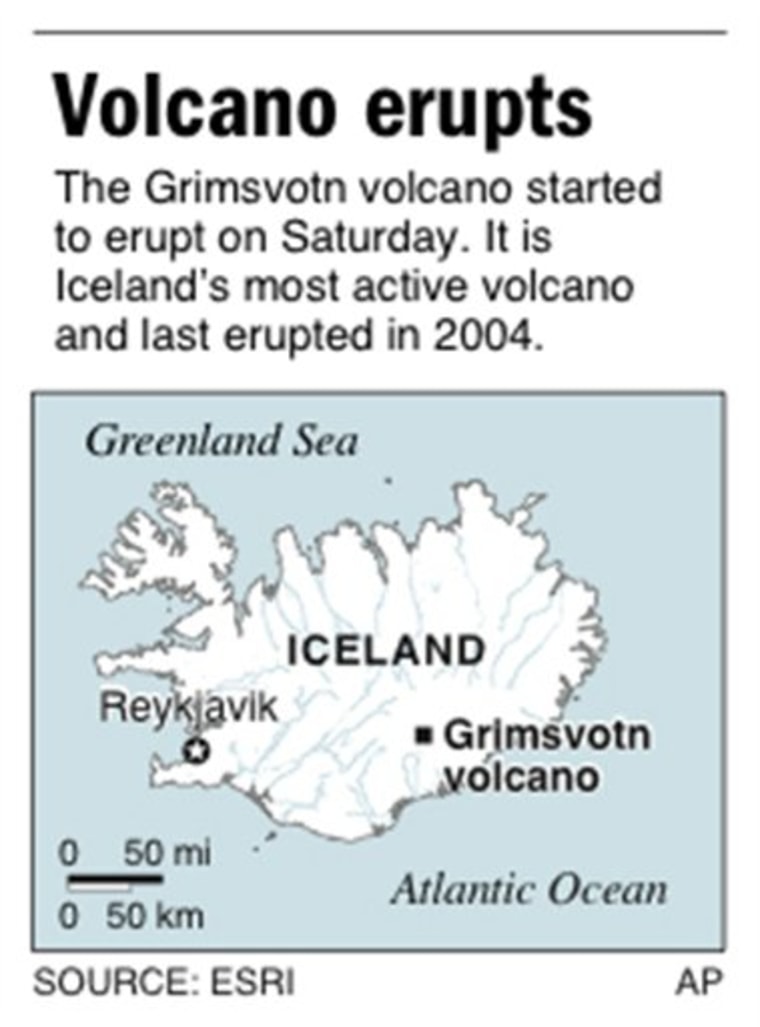

Little did they know that at 6 p.m. in Iceland, the Icelandic Meteorological Office would pick up a surge of seismic activity coming from Grimsvotn, Iceland’s most active volcano, which last erupted in 2004. In a twist to the Camping story, the subglacial volcano began erupting full force, sending a plume of ash 50,000 feet into the air.

Nonetheless, we are of course still here and, because of the volcano’s remote location in Iceland’s uninhabited highlands, nobody was in immediate danger during the four-day eruption, which ceased Wednesday morning. It did, however, produce a tremendous amount of ash that will not disappear so quickly.

In fact, this eruption produced more ash in the first 24 hours than the entire Eyjafjallajokull eruption, which just one year ago paralyzed air traffic around the world and stranded travelers all over Europe.

Iceland’s main road, which goes full circle around the island, was closed from Sunday morning until Tuesday evening between Vik and Freysnes, a 90-mile stretch in southeast Iceland where the ash was at times so thick that it might as well have been the dead of night in the dead of winter.

Passing through Vik just before authorities closed the road on Sunday morning, I experienced first-hand what was probably as close to a doomsday as Camping had envisioned. I was prepared for the ash, but I was not prepared for the hazy brown surroundings to turn pitch black as the ash blocked out the sun completely.

“It feels like being snow-blind,” the photographer accompanying me said uneasily as she navigated the car into darker territory. We made it within kilometers of the next town to the east, Kirkjuaejarklaustur, before we could no longer see even one road marker ahead of us. Stopped in an ash storm, there was no choice but to call Iceland’s rescue team.

( to see photos from the trip to the Grimsvotn volcano.)

A French man we had met earlier driving from Kirkjuaejarklaustur back to the capital Reykjavík had strongly advised us against continuing on our trip. He was here scouting the country for a French tourism company, and would be returning home with a negative impression of Iceland as a viable tourist destination. “I can sell snow, I can even sell rain, but I just cannot sell ash,” he said matter of factly.

The Icelandic government has been understandably worried about the eruption’s impact on the tourism business. Iceland’s president, Olafur Ragnar Grimsson, was harshly criticized for speaking overdramatically when Eyjafjallajokull erupted last year, and the Icelandic Travel Industry Association sent a press release to the media asking that everyone be careful not to overdramatize this eruption.

The recent eruption is the latest in a series of crises to test the resolve of Icelanders in the past few years. First it was the collapse of the banks and the Icesave dispute with the Brits and the Dutch. Then it was the difficult-to-pronounce-eruption that left thousands of travelers, like the infamous “I Hate Iceland” guy, stranded and Iceland’s hotels empty.

“It’s too much,” said Anna Thorisdottir, who was with a group of hikers descending Vatnajokull glacier when the Grimsvotn volcano began erupting beneath the glacier. “We can explain one eruption, but an eruption year after year? People are just going to stop coming.”

Unable to drive west, Anna and her group of hikers headed east, full circle around the island, to return to Reykjavík two days later. In the northeast, they faced snow and icy roads, which is not your every day summer weather, even in Iceland.

The Smyril Line ferry made its first trip of the summer from Denmark to Seydisfjordur, a fishing and tourist village in the Eastfjords of Iceland, over the weekend. Its 600 passengers found themselves stuck in the small town, pop. 668. Grocery stores there were without milk for two days.

Meanwhile, Iceland’s rescue team could be counted on, and we were guided to a community house where the Red Cross was looking after about a dozen others who became stranded in the ash. They pointed to a stack of mattresses and suggested that we make ourselves comfortable.

Local residents Pall Ragnarsson and his wife, Maria Gudmundsottir, had made a big pot of asparagus soup and an assortment of open-faced sandwiches. The clock read 1:30 in the afternoon, but everything else pointed more to 1:30 in the morning.

“I thought I would have time to knit today,” Maria said pointing to her bag full of unfinished work, “but we’ve had about 50 people, counting nurses and the rescue team, come in and out.”

Then just as we had prepared to spend the night, the wind died down, the hazy brown landscape reappeared and a local policeman informed us that we could drive back to Reykjavik. “But hurry,” he said.

Ultimately, it’s not travelers or tourists who face the brunt of the eruption but Iceland’s farmers, who have to deal with the ash. To help them with the cleaning efforts, the government has put to work Iceland’s unemployed, which are at 8.3 percent today compared with 1 percent before the economic crisis hit in 2008.

With the exception of southeast Iceland, the country is largely free of ash, and those travelers grounded in Reykjavík have been granted free admission to museums and swimming pools.

Life on this island, which sits on the mid-Atlantic ridge, has been unusually shaky, but an impending doomsday? Not so much. Birds are singing again in Kirkjuaejarklaustur and at the time of writing, flights are slowly resuming to normal.

Anna Andersen is a journalist at . to see photos from her trip to the Grimsvotn volcano.