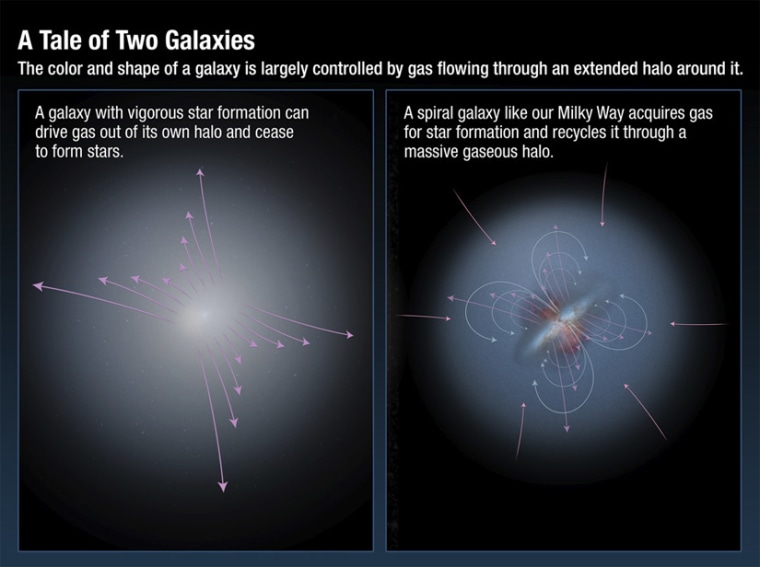

Some galaxies have strict rules on recycling, but others are reckless and rapidly dump stellar gas into intergalactic space, resulting in them paying the ultimate price: a premature death.

So, if a galaxy wants a long, happy life, it pays to be sustainable — this means "going green" on a galactic scale.

These findings are due for publication in three separate papers in the Nov. 18 issue of the journal Science. The three studies are headed by Nicolas Lehner of the University of Notre Dame in South Bend, Ind.; Jason Tumlinson of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Md.; and Todd Tripp of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Recycled halos

Using the Cosmic Origins Spectrograph (COS) aboard the Hubble Space Telescope, the three teams have identified vast "halos" of gas surrounding a selection of 40 galaxies.

Previously invisible, these halos are much larger than believed and act as reservoirs for recycled "star stuff" — light elements such as hydrogen and helium, and heavier elements such as carbon, oxygen, nitrogen and neon. Some galactic halos reach as far as 450,000 light-years from their visible galactic disks.

The astronomers found that our galaxy also has a halo extending up to 20,000 light-years from the Milky Way's disk, providing an explanation as to the mysterious source of gas that supplies our galaxy.

But not only are these halos bigger than previously believed, the astronomers were surprised to find that there is as much gas inside the halos as there is between the stars within a given galaxy.

"There's as much heavy elements out in the halos of the galaxies as there is in their interstellar medium," Tumlinson told Discovery News, "that is what shocked us."

The heavier elements detected in galactic halos can only be formed inside stars and the waste products of supernovae — powerful explosions that result from massive star death.

However, rather than venting and losing these waste gases to intergalactic space, the halos are replenished and provide an invaluable "feedback loop" where the gas falls back in to the galaxy, helping to create new star birth.

The halos observed by COS therefore support not only star birth, but also planets, complex organic molecules and, ultimately, life.

We are (recycled) star stuff

The Milky Way's halo contains enough ionized hydrogen to create 100 million stars and enough gas "feeds" our galaxy to create one star per year. This halo is then replenished with gases from supernovae and stellar winds — hydrogen laced with a cocktail of heavy elements — to sustain star birth for another billion years, the researchers estimate.

Interestingly, as Tumlinson speculates, this large-scale recycling of elements in our galaxy has implications for not only our sun, but us personally.

"Your body is 70 percent water and every water molecule has an oxygen atom in it," he said. "The theorists say the recycling time (in the Milky Way's halo) is approximately a billion years, so that means — potentially — that some of the material (oxygen) inside your body has cycled in and out of the galaxy 10 times in the history of the galaxy. At least once, maybe up to 10 times."

To quote Carl Sagan, "We're made of star stuff," perhaps in light of this research, it should read: "We're made of recycled star stuff."

The "Amy Winehouse" of galaxies

However, this scenario isn't universal. The researchers found that there must be a balance between star birth and halo replenishment. If demand outstrips supply, then there's a problem; a galactic-sized sustainability problem.

In the case of young galaxies that underwent rapid star creation (commonly referred to as "star burst" galaxies), the violent star production phase resulted in a rapid expulsion of enriched stellar gas.

"We found the James Dean or Amy Winehouse of that population, you know, the galaxies that lived fast and died young," Tumlinson pointed out. "(Todd) Tripp's team studied that in their paper."

"That paper used a galaxy that is known as a 'post-star burst galaxy' and its spectrum showed that it had a very robust star burst (phase)," he continued. "It was one of those live fast, die young galaxies."

Unfortunately for these galaxies, the waste gas didn't hang around in a neat halo ready to supply the material needed to birth baby stars. Instead the gas was lost to intergalactic space, starving the galactic halos.

The COS instrument has clocked the waste gas from galaxies with high star production rates traveling at 2 million miles per hour — fast enough for the gas to be lost from the galaxy forever.

"So not only have we found that star-forming galaxies are pervasively surrounded by large halos of hot gas," said Tripp in Thursday's press release, "we have also observed that hot gas in transit — we have caught the stuff in the process of moving out of a galaxy and into intergalactic space."

It therefore pays to be a galaxy with a low star production rate. These galaxies produce slower streams of waste gases that collect in galactic halos that in turn get recycled by future star birth.

The moral of the story is that when mom tells you to do "everything in moderation," tell her that she is universally correct.