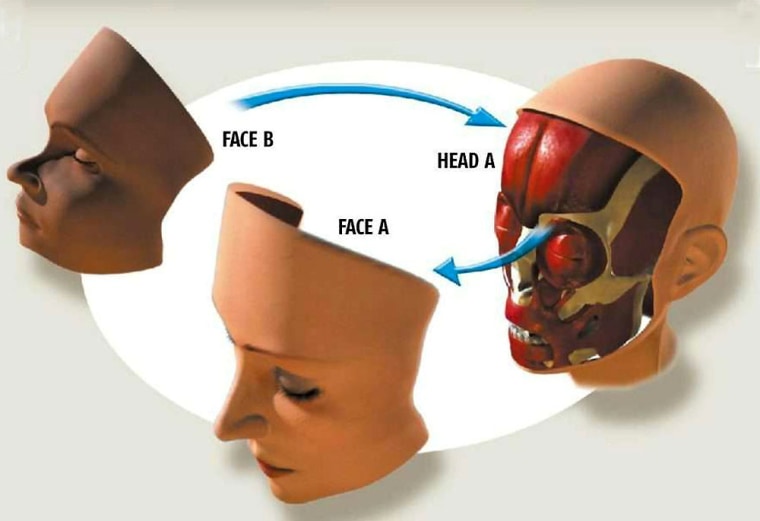

A team of doctors at the University of Louisville in Kentucky is moving forward with a plan to attempt the world’s first face transplant. They have applied for permission from the University’s research ethics committee to remove a face from a cadaver and transfer it to a live volunteer willing to go through with the surgery. If approved, the operation could take place before the end of this year.

For those who have suffered terrible physical trauma, such as burns or the ravages of oral cancer, and who have been unable to adjust to their disfigurement, this radical new form of surgery offers tremendous hope. However, the ethical question is whether these surgeons are really ready to offer this hope.

The reason the team at Louisville believes they are prepared to try this incredible operation is that they have already been successful in transplanting hands taken from cadavers. To date, one of the most difficult tissues to transplant is skin. The body’s first line of defense is especially sensitive to foreign tissue and, as a result, skin transplants have limited what could be done with limbs, hands or other external organs. The Louisville group has developed a powerful combination of drugs that helps prevent the body from rejecting transplanted skin, allowing for their success with hand transplantation. The team believes they can apply this technique to face transplants as well.

Patient faces enormous risk

There are apparently many volunteers willing to undergo a face transplant. While some people who have endured facial disfigurement learn to adjust, others do not. They would gladly take the risks involved in such a surgery for a chance to regain the normalcy that, in our appearance-conscious society where people undergo multiple surgeries just to look younger, is difficult to achieve with a severely deformed face.

The problem is that there are a number of very real and serious risks confronting the first subject. For example, the drugs used to prevent rejection by the body may fail, leaving the recipient with the nightmare of the transplant being rejected and, with death likely to quickly follow, no other options. In addition, the drugs involved are so toxic that cancer, kidney failure and other problems are likely to eventually occur, even if the initial surgery is successful.

Even more challenging is the problem of adjusting to a new face. While those with severe facial deformities might hope for any alternative, a transplanted face that does not work right, looks strange or reminds people of someone who is dead, would pose very difficult challenges to anyone who receives it.

Should donor's family help decide?

And how will a donor be selected? Remember -- until you know who your pool of recipients is likely to be, you cannot match possible donors for blood type, size and other biological factors. As a result, the decision about who will donate and who will undergo the surgery is likely to be a last-minute one.

Should the pool of possible donors only include those who have signed a donor card or who sign a document including their face among those organs and tissues they are willing to give? Or should their families be able to make the decision without a donor card since they are the ones who will have to live with whatever happens when the surgery is completed and someone else receives their loved one’s face?

These are among the most difficult ethical questions ever to confront the field of transplantation. Thankfully, the Louisville team is trying to explore and discuss these issues before they proceed. Let’s hope that they -- and other surgical teams in the United States, France and Britain who are also gearing up to be the first to perform this unprecedented procedure -- have the good judgment not to proceed until all of these questions have been answered.

Arthur Caplan is director of the Center for Bioethics at the University of Pennsylvania.