Humans can live without a lot of things on Earth — cable television and Twinkies, for example — but air isn't one of them.

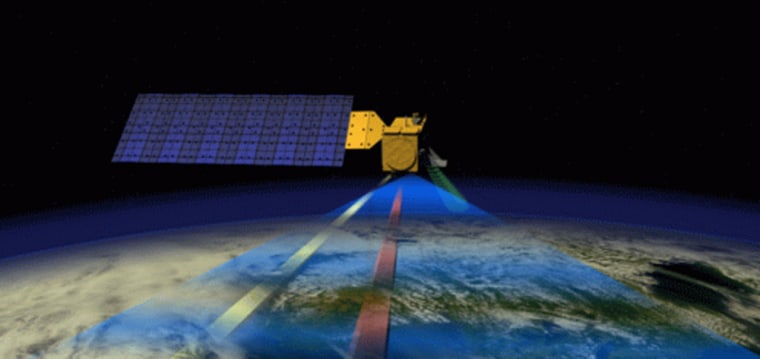

Now a new NASA satellite is poised to take the closest look ever at the air humans breathe to understand how smoke, aerosols and other pollutants can be carried through the atmosphere and affect air quality around the world.

The Aura spacecraft, the latest and last satellite NASA's first Earth Observing System, will also monitor changes in Earth climate and search the planet's ozone layer for any signs of recuperation after years of attack by human-made pollutants such as chlorofluorocarbons.

"It truly is a chemistry lab in space," said Michael Tanner, Aura's lead engineer and the mission's program executive at NASA headquarters, of the spacecraft. "If it works for one day we will have more information on our air than ever seen from space."

Aimed for an orbital slot 438 miles (705 kilometers) above Earth, Aura will focus its attention on the stratosphere, home to the ozone layer, and the layer of breathable air stretching down to ground level. The spacecraft will fill the atmospheric gap left by its EOS satellite comrades Aqua, which studies Earth oceans, and Terra, aimed at land masses.

The spacecraft is expected to launch no earlier than July 3.

The air we breathe

Nestled among the four instruments aboard Aura is a device called the Tropospheric Emission Spectrometer, or TES, that will study the layer of the atmosphere in which most people live, work and play.

That layer, the troposphere, starts on the ground and stretches about 6 miles (10 kilometers) up to the stratosphere, where the ozone layer screens the planet from ultraviolet radiation.

Space-based observations of the troposphere are traditionally difficult due to interference from clouds that sit between satellites and the atmosphere's bottom-most layer. Aura's TES instrument, however, is designed look downward and horizontally at the same time. The configuration should be able to track air pollution caused by Mother Nature through volcanoes or wildfires, as well as by man, including the burning of trees and other biomass in the tropics and industrial byproducts in North America and China.

"Mostly, it's considered a local problem, but it's really a global one," Aura project scientist Mark Schoeberl, based at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, said during a telephone interview. "We need to understand how well pollutants can get from the United States to Europe, for example."

Dust from deserts in China, for example, can waft out over the Pacific Ocean and affect air quality in the Pacific Northwest, and smoky air from Canadian wildfires stretched from New York to Washington, D.C., in 2002.

With a better understanding of how such pollutants are transported through the atmosphere, researchers would be better equipped to issue air quality warnings for residents who might otherwise suffer health problems.

Ozone checkup

Aura's second target is the ozone layer in the stratosphere, a protective layer of the atmosphere that has been closely watched since the 1970s, when satellite measurements first began recording signs of ozone depletion due to human-made pollution.

The spacecraft's Ozone Monitoring Instrument, or OMI, will map changes in the ozone layer as well as the levels of nitrogen dioxide and other pollutants. Along with two other Aura instruments, OMI should help researchers pin down any mixing between protective ozone in the stratosphere and pollution-generated ozone in the upper troposphere.

"There is such a thing as good ozone and bad ozone," Tanner told Space.com.

Aura instruments are also designed to detect greenhouse gas levels and measure how aerosol particles reflect or absorb sunlight, which could contribute to climatic changes such as global warming and cooling trends.

The Aura spacecraft won't be alone in space during its planned six-year mission.

Once aloft, Aura will trail the Aqua spacecraft in a formation flight pattern to make comprehensive climate observations of the Earth. In 2005, the cloud-watching satellites — CloudSat and the Calypso — are expected to fill in the gap between the two EOS spacecraft, with the French-developed Parasol satellite to join them in 2006.

Mission scientists have dubbed the five-spacecraft formation the "A-train," in which each spacecraft passes over a region 15 minutes after its predecessor and takes data that can ultimately be combined into a complete climate picture.

"We've come up with this sort of super assault on the atmosphere," said Schoeberl, adding that while the multiple spacecraft will follow each other, they will be at different orbital inclinations. "We'll really be able to look at the interaction between the climate and the atmosphere."

The train won't run forever, though. Its engine, Aqua, has already been orbiting for about two years and could be a limiting factor for the complete satellite constellation. Aura itself, the train's "caboose," could last much longer.

"It has enough propellant to last eight to 10 years," Tanner said, adding that some older Earth-observing satellites have outlived their designed lifetimes by 12 years or so. "These observatories, in all aspects, are quite tough."