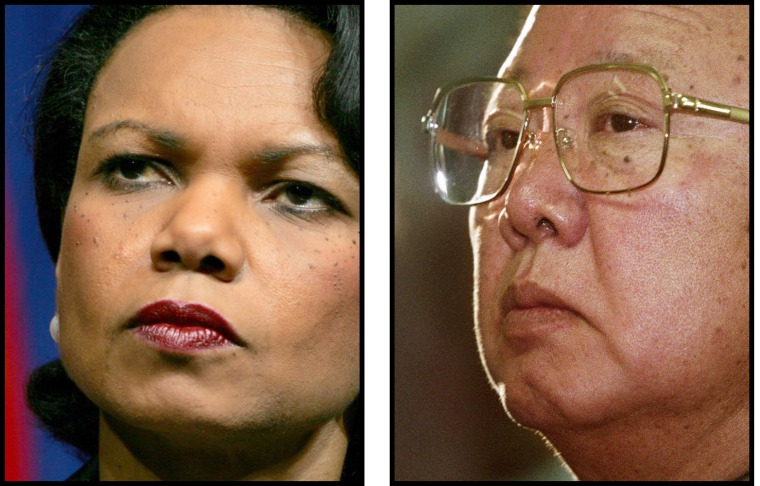

Even before being anointed as secretary of state, Condoleezza Rice began jousting with North Korea — a nation deemed a dangerous nuclear problem and led by a perennial psychological puzzle. She has visited Asia to press for talks, and sent her second in command to the region. But three months into her tenure, wrestling this foreign policy demon to the ground seems more remote than ever.

On Wednesday Rice's deputy, U.S. Assistant Secretary of State Christopher Hill, left Beijing with no sign that Pyongyang would return to talks on ways to halt its pursuit of nuclear weapons.

“The future of talks is very much uncertain at this point,” Hill told reporters. “We continue to have a North Korean regime that is very ambivalent about whether it wants to find a negotiated settlement to this.”

It also emerged on Wednesday that North Korea would not send any representative to Moscow next month for Russian World War II victory celebrations, which some hoped would be a venue for backroom contact with the reclusive regime.

Meanwhile, unsettling, though unconfirmed, speculation cropped up in press reports that North Korea might be preparing to test a nuclear weapon— a move that would transform the simmering diplomatic problem into a front-burner crisis.

Can Rice, something of a puzzle herself, deal with Kim Jong Il, an enigmatic, rather disheveled dictator who wields absolute political control and exhibits a dangerous mixture of cunning and paranoia? Will she match cunning with cunning, or just rhetoric with rhetoric?

If the self-proclaimed pragmatist is planning to do any horse trading with Kim or plans to soften the harsh tone set by President Bush in his first term, she hasn't made it evident.

On Wednesday, she declared her unwavering support for Bush's nominee, John Bolton, as U.S. ambassador to the United Nations. The controversy over Bolton that has captured headlines is his alleged abusive management style. But from Pyongyang's perspective, Bolton is perhaps the most disliked and distrusted of American officials — one who would wield immense power over proposed sanctions or other international punitive measures aimed at North Korea.

Rough start

Rice set the tone right from the start, in confirmation hearings for her post on Jan. 18, calling North Korea one of the world's "outposts of tyranny."

The blunt language, which may have been directed more at a U.S. audience than at Kim, definitely got Pyongyang's attention. It immediately distinguished her from predecessor Colin Powell, who actually made noises about direct talks with North Korea, one likely reason Powell fell out of favor among the neo-cons in Washington.

On the face of it, Rice had already undermined the modest progress made by the six-party talks that started in 2003 to end Pyongyang's nuclear ambitions.

By the time Rice began her first official trip to Asia on March 14 with the aim of restarting the talks, Pyongyang had harrumphed its displeasure with her through its official news agency, calling her “reckless” and “bereft of political logic.” It said it would not rejoin the talks unless she apologized for the "outpost" statement.

Rice did not apologize, and by the time she headed home a week later, Pyongyang had announced "serious steps of boosting (its) nuclear arsenal" according to the nation's official news agency, further raising the stakes. In turn, Rice strongly hinted at tougher sanctions against Pyongyang unless it rejoins the talks, which include Russia, Japan, China and South Korea.

Don't attack 'the eyes'

Rice is still in the game, say experts, despite the North Korean reaction to the "outpost" statement — that is, she has not approached the type of insult that really makes Pyongyang mad.

On the other hand, her support for Bolton has led to complete alienation from North Korea. In a 2003 speech in Seoul, South Korea, Bolton, then undersecretary of state for arms control and international security, called Kim Jong-Il a "tyrannical dictator" who had made North Korea a "hellish nightmare." He also talked openly about the U.S. quest for regime change in Pyongyang.

Pyongyang called Bolton "human scum" and shunned the six-party talks until he was pulled from the ranks of negotiators.

"Language does matter, in the sense that the North Korean regime is very 'face conscious,'" says Bradley Martin, a long-time Asia correspondent and author of a new book on North Korea. He contends that although Rice has offended Pyongyang, she has not attacked Kim Jong Il personally — and that is an important difference.

During a 1989 reporting trip to North Korea, "an official had told me pointedly that the bottom-line minimum was that Westerners who wanted any sort of relationship with Pyongyang at all must stop making fun of its leaders," writes Martin in his book, "Under the Loving Care of the Fatherly Leader." The official advised Martin not to hit "in the eyes," which in North Korean code refers to the regime's leader.

By not crossing that line into the personal, Rice may still have the ability to bring Kim back to the table.

And Pyongyang could reverse its rhetoric. Former President Jimmy Carter, who was labeled a "vicious political mountebank" in 1979 because he denied North Korea bilateral talks, was in 1994 the man who got through to Kim, and found a temporary resolution to the standoff over nuclear weapons.

As a result, "the threat of immediate war receded," says Martin.

Downward spiral

The United States fought alongside South Korea in the 1950-53 Korean War, which ended with a cease-fire, not a peace agreement. The United States maintains some 37,000 troops in South Korea, facing off with the North Korean military on the peninsula, which is divided at the 38th parallel.

The latest crisis in the standoff began in 2002, when President Bush called North Korea part of an "axis of evil" alongside Iraq and Iran. In October, Pyongyang said it had a uranium enrichment program, violating the spirit, if not the letter, of a 1994 deal under which Pyongyang agreed to mothball its nuclear programs. The United States suspended oil supplies provided to North Korea under the 1994 agreement, prompting Pyongyang to pull out of the 1968 Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty and kick out U.N. nuclear monitors.

Now North Korea claims it is pursuing a nuclear deterrent, and probably can produce at least a few crude nuclear weapons. It demands a nonaggression agreement with the United States before it agrees to stand down, but the Bush administration demands it stand down first.

"The crux of the matter is that things have broken down to such an extent that she is essentially facing putting it all back together from scratch," Eric Heginbotham, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, says of Rice. "We're in a state of drift."

Kim emerges, he's sane and can do business

One advantage for Rice is that there is more information about Kim than in the past. When he took the reins after the 1994 death of his father Kim Il Sung, the younger Kim was almost a complete enigma. Profiles dwelled on his reported love of fast cars, obsession with Daffy Duck cartoons and speculation that he may be mentally retarded or delusional. A decade ago, intelligence officers didn't even know what Kim's voice sounded like — there were no recordings of it.

But when Kim finally emerged, perceptions changed. Former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, who held missile talks with Kim in the waning days of the Clinton administration, describes Kim in her book, "Madam Secretary: A Memoir," as "an intelligent man who knew what he wanted" — primarily normal relations with Washington as a means of ensuring his country's security.

The talks ultimately failed to produce a missile agreement but Albright said Kim came across as serious about negotiating.

Japanese President Junichiro Koizumi also traveled to Pyongyang to an unprecedented top-level summit in 2002. Kim surprised Japan by admitting that his country had, as many Japanese had suspected for decades, kidnapped and brainwashed a handful of Japanese children in the 1970s. The admission backfired, setting off a wave of pent-up public anger in Japan.

Nonetheless, it showed that Kim did respond decisively to frank discussions at a high level, so long as they were polite.

Albright's experience showed, too, that a woman, at least a very highly placed one from the United States, can deal with Kim, despite the dearth of women in either North Korean or South Korean politics.

But experts suggest that for Rice, a deference for age and a show of humility could help.

"More important than age, is an awareness of age," says Heginbotham. "If you are younger than Kim Jong Il, it’s probably important to acknowledge that."

For Rice, beyond the challenge of setting a course on North Korea, is the challenge of winning consensus among White House insiders, a consensus that has so far evaded the Bush administration. That may be an even bigger show of diplomatic finesse.