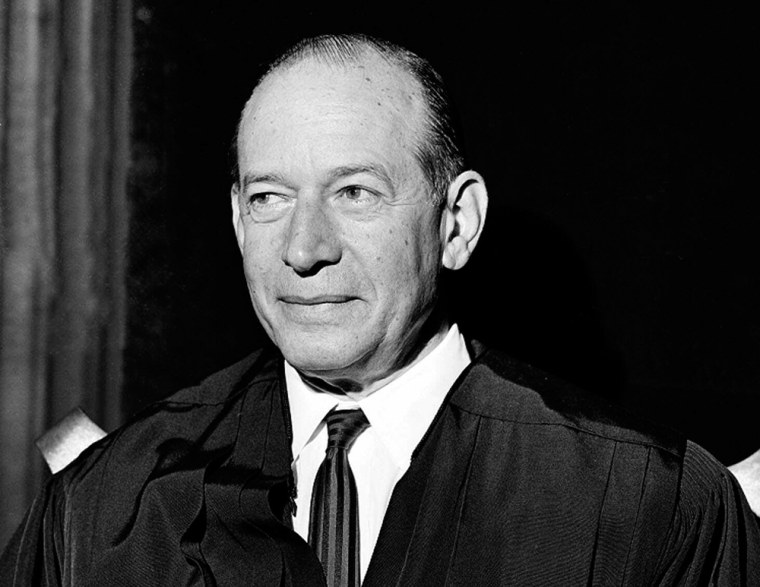

In the raging Senate battle over judicial filibusters, Abe Fortas’s name comes up so much you’d think that he was one of the people now being nominated for a spot on the federal bench.

Senate Democratic Leader Harry Reid of Nevada kicked off debate on the Senate floor Thursday morning by brandishing a giant-sized reproduction of the front page of the Sept. 26, 1968 edition of the Washington Post, pointing to the headline, "Fortas debate opens with a filibuster."

"He was successfully filibustered," Reid declared.

Fortas was the Supreme Court justice and long-time confidant of President Lyndon Johnson whom Johnson tried to elevate to chief justice.

Republicans and Democrats have battled over the meaning of the Fortas fight for a very good reason: it is a precedent for a filibuster battle over President Bush’s appeals courts nominees and precedent perhaps for a Democratic attempt to filibuster Bush’s nominees to the Supreme Court if there is a vacancy, as expected, this summer.

On June 26, 1968, Johnson nominated Associate Justice Fortas, whom he’d placed on the court in 1965, to be chief justice, replacing the retiring Earl Warren.

There are sharp differences between the 1968 fight and any Supreme Court nomination Bush would make this summer:

- Johnson was an enormously unpopular lame duck in the final six months of his presidency, a man repudiated by his own party in the 1968 primaries. Bush has three years, eight months left in his presidency and has the almost-unanimous support of his party on the judges issue.

- Republicans had a good chance to win the 1968 election and wanted to keep Warren’s seat open for the new Republican president.

- The vote on ending debate on the Fortas nomination didn’t come until Oct. 1, 1968, a mere month before the election.

- A bipartisan coalition defeated Fortas; any filibuster this summer would be a purely Democratic effort.

Lengthy hearings before the Judiciary Committee brought to light much information that damaged Fortas, including the fact that after joining the court, he had violated judicial ethics and the principle of separation of powers by regularly going to the White House to draft Johnson’s speeches and advise him on Vietnam War policy.

Outside income from business leaders

The hearing also revealed that Fortas, whose salary as a justice was $39,500, had accepted a $15,000 payment to lead seminars at American University. It turned out that Fortas’s former law partner raised the money from a coterie of business moguls, including the president of the New York Stock Exchange and the vice president of Philip Morris.

Sen. Robert Griffin, R- Mich., led an alliance of Republicans and Southern Democrats determined to scuttle the nomination.

In a letter written in 2003, former Sen. Griffin denied there was a filibuster, in the sense of an endless debate that kept Fortas from getting a straight up-or-down vote. The debate lasted only four days.

On Oct. 1, 1968, the Senate voted on a cloture motion — to cut off debate and proceed to the nomination itself.

Under Senate rules at the time, 59 votes were needed to end the debate, two-thirds of those present and voting, and move on to a straight up-or-down vote on the nomination.

The tally was 45 (35 Democrats, 10 Republicans) to end debate, 43 (24 Republicans, 19 Democrats) to continue it.

Fortas then asked Johnson to withdraw his nomination.

Griffin wrote in 2003 that the cloture vote “demonstrated that the White House could not produce the showing of a majority in favor of the nomination.”

Historians see filibuster

Two historians who have written biographies of Fortas both say that what happened in 1968 was indeed a filibuster.

“Both Abe Fortas and LBJ are spinning in their graves at the notion there was no filibuster,” said Laura Kalman, professor of history at the University of California at Santa Barbara and author of Abe Fortas: A Biography. “It was understood as a filibuster at the time.”

Republicans argue that what is unprecedented about the filibuster threats that blocked votes on ten Bush judicial nominees in 2003 and 2004 is that each of those nominees had majority support — in each case more than 51 senators voted for cloture.

In the case of Miguel Estrada, for instance, 55 senators voted to end the filibuster and in all likelihood those 55 would have voted for his nomination. By way of comparison, in 1991, only 52 senators voted to confirm Clarence Thomas, whom Democrats had decided to not filibuster.

Would Fortas, likewise, been confirmed, had there been no filibuster?

It’s impossible to know for sure: one senator who voted for cloture, Kentucky Republican John Sherman Cooper, indicated he would vote against Fortas on an up-or-down vote.

Four Democratic senators, including one who’d spoken out early in strong support of Fortas, simply didn’t show up for the vote.

Kalman said, "Though historians hate ‘what if?’ questions, I think LBJ and Fortas could have believed Fortas would have been confirmed if there had been no filibuster. That was why they kept pressing forward, as [Johnson aide Joseph] Califano says, to let Fortas keep his head up with a majority regarding cloture. If they thought they could get a majority on cloture, I reason, they must have thought they could get a majority on confirmation.”

Fortas would have won

“I have no doubt that Fortas would have been able to get a majority of the votes in a straight up-or-down vote on his nomination,” said Prof. Bruce Allen Murphy, who teaches law and government at Lafayette College. Murphy’s 1988 book is "Fortas: The Rise & Ruin of a Supreme Court Justice."

“Had that not been true, the Republican-Dixiecrat alliance would not have been fighting such a desperate war to prevent this vote, even to the point in the Judiciary Committee of Strom Thurmond reading pornographic literature during questioning and showing pornographic movies to the press corps to illustrate his charge that Fortas was pro-obscenity on the Court, which in fact he was not.”

A lesson of the Fortas battle is that the nominee can help scuttle himself if he is not candid about his own behavior.

Murphy said the Republican-Dixiecrat delaying strategy would not have worked through the summer of 1968 “had Fortas not made himself so vulnerable by his own actions,” such as his moonlighting as a Johnson strategist while on the court and his mogul-funded American University seminars.

“In the end, word was being privately passed, likely from the Nixon campaign, to Sen. Jacob Javits, R – N.Y. and others, that another ‘bombshell’ about Fortas's ethics was on the horizon,” said Murphy. “It was this whisper campaign that kept the filibuster alliance in place and made any cloture vote impossible”

That bombshell, revealed in May 1969, was that in 1966 Fortas had signed a deal with financier Louis Wolfson to receive lifetime annual consulting fee of $20,000 from Wolfson’s foundation. Wolfson was imprisoned in 1968 for stock manipulation. Fortas had cancelled the deal after several months in 1966, but the revelation forced him to quit the court in 1969.

The biggest change in judicial politics since 1968 is that the screening of nominees has become a science.

Johnson knew Fortas like a brother and seemed blind to his unethical conduct. Any Bush nominee will be fully screened, scrubbed, rehearsed, and armed to answer senators’ questions.