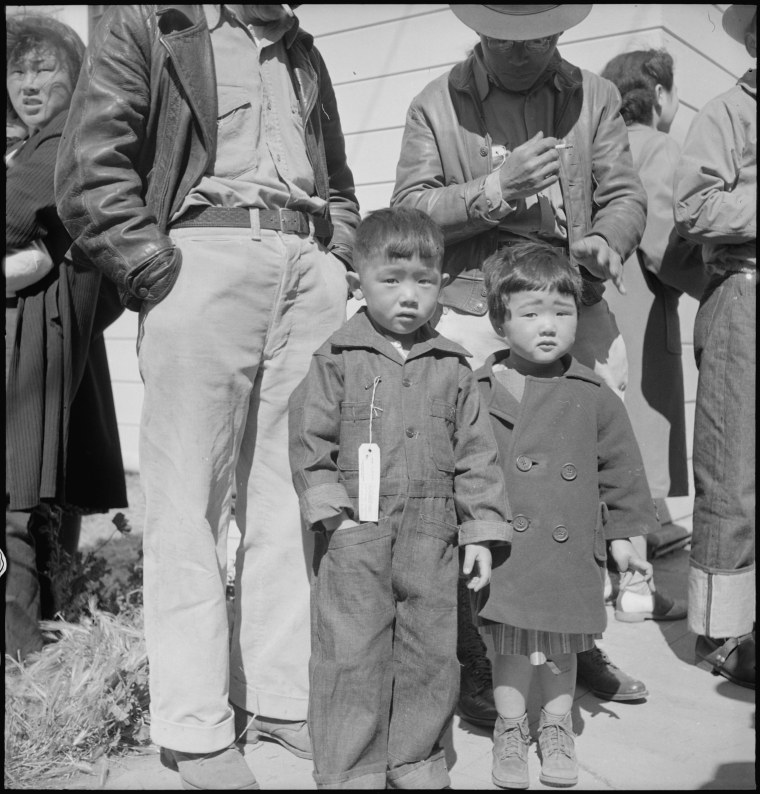

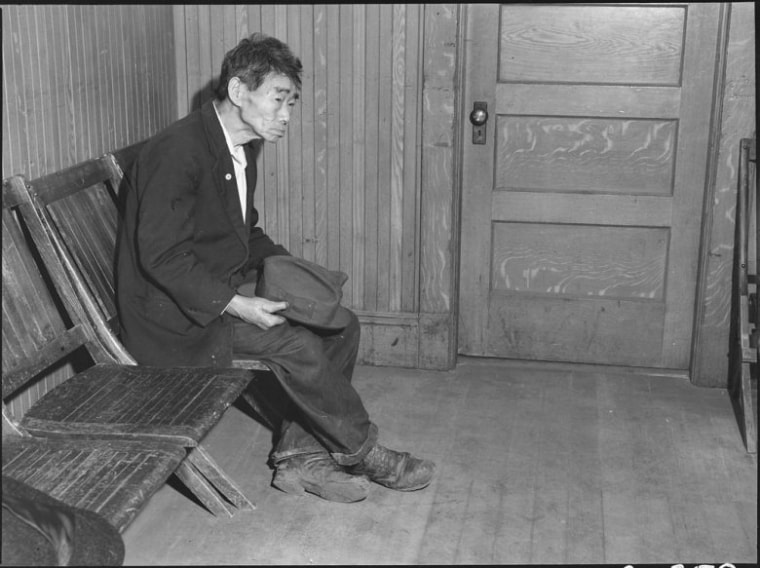

Densho, a non-profit organization dedicated to preserving the history of Japanese-American incarceration during WWII, recently highlighted the work of photographer Dorothea Lange, whose photographs were placed under government embargo for thirty years.

Natasha Varner, Densho’s communications manager, emphasized the importance of Lange’s work in an organization blog post. “Lange’s exclusion-era photographs helped catalyze Japanese-American activism in the 1970s, and they continue to powerfully shape the collective memory of one of the darkest moments in American history,” she wrote.

Lange, known primarily for her photographs of Dust Bowl America during the Great Depression, was hired by the War Relocation Authority (WRA) in 1942 to document the removal and imprisonment of Japanese Americans.

Lange had personal misgivings about the work, according to Densho: She told a friend that she was “appalled” by a “federal government who could treat its citizens so unjustly.” The organization said she was also frustrated by the WRA’s censorship, which explicitly banned Lange from photographing barbed wire and bayonets. She quit after just a few months, but not before producing “a body of work that at once captured the inhumane actions of the US government and the humanity of the individuals being forced to leave their lives behind for the 'crime' of Japanese ancestry.”

RELATED: Digital Project Aims to Preserve Stories of Incarcerated Japanese Americans

The federal government, seeing these photographs as potentially damaging press, embargoed them for 30 years, according to Densho. They were released for public viewing in 1972, when they were featured in the landmark traveling exhibition, Executive Order 9066.

Brian Niiya, Densho’s content director, told NBC News in an e-mail that the exhibit, and the release of the Lange photographs, was timely.

“The exhibition came in the context of increasing sympathetic media coverage of the Japanese American WWII story,” he said. “At the same time, there was also increasing interest within the Japanese American community, largely driven by Sansei coming of age and influenced by the 1960s-1970s social movements.”

“There is [an] oft-told story about Sansei [third-generation Japanese-American] kids first learning about the incarceration in school and confronting their parents about why they never told their kids about this," he continued. "(The most famous such story is that of Karen Korematsu, who learned about her father's landmark Supreme Court case in school!)”

Niiya wrote that exhibitions of photographs such as Lange’s, which had never been seen to the public before, helped catalyze political movements within the Japanese-American community.

“Along with camp pilgrimages, political activism around the repeal of Title II, and a flood of new books, these exhibitions were part of the changing attitudes to the Japanese American wartime experience in the early 1970s that led to the Redress Movement of the 1980s,” he wrote.

Follow NBC Asian America on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Tumblr.