Photos have the power to capture a moment forever, but sometimes, the more you look at a portrait, the less you know about the people in them. This is the case with many family photos that have been forgotten over time. You may recognize your parents and grandparents, but not know who is standing next to them. And if you go back even more generations, the distance between your family and those people gets even bigger.

This distance has created invisible barriers between the children and grandchildren of many immigrants, who don't know of the bonds created by their family members - even a century before - in neighborhoods across the U.S.

"I am the grandson of Asturianos (Spaniards from the section of Asturias) who immigrated to the United States at the beginning of the 20th century," said New York University professor James Fernández Wednesday at the presentation of his new book "Invisible Immigrants" in Washington D.C. And like the descendants of many immigrants, Fernández kept his family story separate from the stories of other Spanish-Americans.

Even though the NYU professor had taught Federico García Lorca's poetry for years, it took him a long time to come to terms with the idea that the acclaimed Spanish poet and his grandfather José could have lived in New York during the same period, much less share anything in common as expats in the city.

Fernández and his "Invisible Immigrants" co-editor, Spanish journalist Luis Argeo, have been documenting the history of different Spanish immigrants in the United States since 2010. They realized early on that because many descendants had lost contact with their Spanish origin, valuable photos and documents could also be lost.

Follow NBC News Latino on Facebook and Twitter

"These documents are in danger... because many of their owners, including myself in the past, don't recognize the historic value that their personal archives have for society," said Fernández.

One such story describes how the son of a poor immigrant family became the mayor of Monterey, a city that had been the capital of California during Spanish and Mexican rule. Fernández pointed out that Albert's story helped him connect with the descendants of other Spanish immigrants who had similarly immigrated to Hawaii before settling in California. And now, with the success of a documentary produced and directed by Fernández and Argeo about Albert's life, the Monterey Public Library started a digital campaign to preserve the photos and documents of Spanish immigrants.

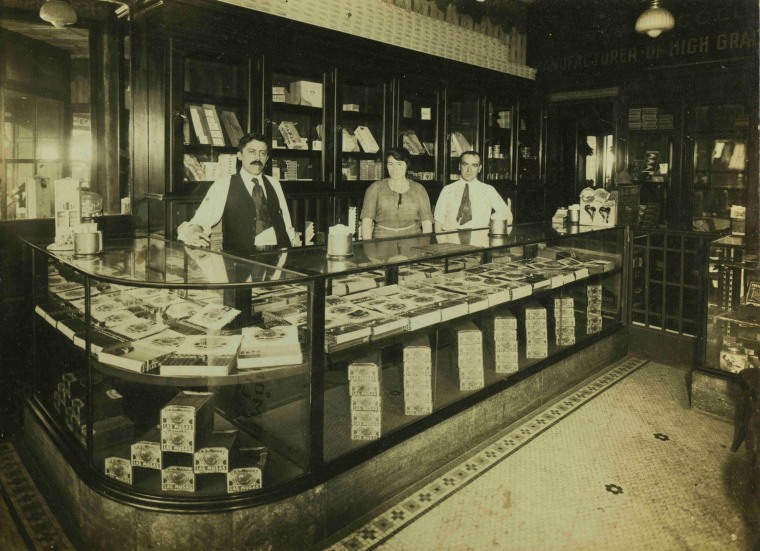

"Invisible Immigrants" collected 324 photos from 80 different sources; it offers snapshots of everyday life, including immigrant shops and factories, family reunions, weddings and picnics.

The book itself is a tribute to the solidarity that kept these early immigrant communities together. And it inspired Fernández and Argeo to publish "Invisible Immigrants" as part of a larger community effort on Kickstarter.

"Immigrants didn't invent crowd funding but they raised money to support each other in many ways," Fernández told NBC News. "You can find [newspaper] listings with the names of supporters who raised money to help immigrants recover from injuries, return to Spain, and other [causes]."

Fernández and Argeo were able to raise almost $45,000 from 360 people, ranging from $1-$5,000. The majority of the photos are from the descendants of immigrants who have also literally bought into the publication of the book.

In the last 7 years, Fernández and Argeo have built an archive of almost 7,000 photos. And they have successfully used Facebook to connect with other descendants to map out family stories in the United States and other countries that share a history with Spanish immigration like Cuba and Argentina.

Fernández and Argeo stress that "Invisible Immigrants" is a community-owned project. In this case, they see themselves as "curators" of the immigrant story.