“Why can’t I?” the girl said with a mouthful of food that, technically, still belonged to the grocery store they were standing in. Erica Clark, 37, couldn’t help but smile as the girl finished eating what she’d unabashedly taken off the shelf.

“I thought, ‘yeah, why can’t you?’” reflects Clark.

For 10 years Clark taught children with Autism and Down syndrome, a job she fell into when assigned to be a substitute teacher in a special-education classroom. Last year she stopped teaching to pursue her burgeoning stand-up comedy career and she took something of them with her.

“I admired [my students],” said Clark. “They didn’t care what anyone else thought. It was so refreshing; there was no sugar coating with them.”

Growing up in Lake Forest, an affluent Chicago suburb, Clark was the only African-American student in her high school until her senior year. “It wasn’t terrible, I never got bullied or anything like that I just think that it’s very strange to be the only person of a certain race in a school of 1500 kids," said Clark.

When Clark tells people she’s from Lake Forest, a neighborhood that according to 2010 census data is 90 percent caucasian, they ask if her father is a member of the Chicago Bulls. He isn’t.

“I always thought it was funny. My dad had on gold chains and everyone else’s dad had on a suit. Of course I know it wasn’t normal.”

Clark’s father is an acting, wrestling, ex-football playing army veteran who once chopped down 70 trees in 3 hours and served as Muhammad Ali’s personal bodyguard.

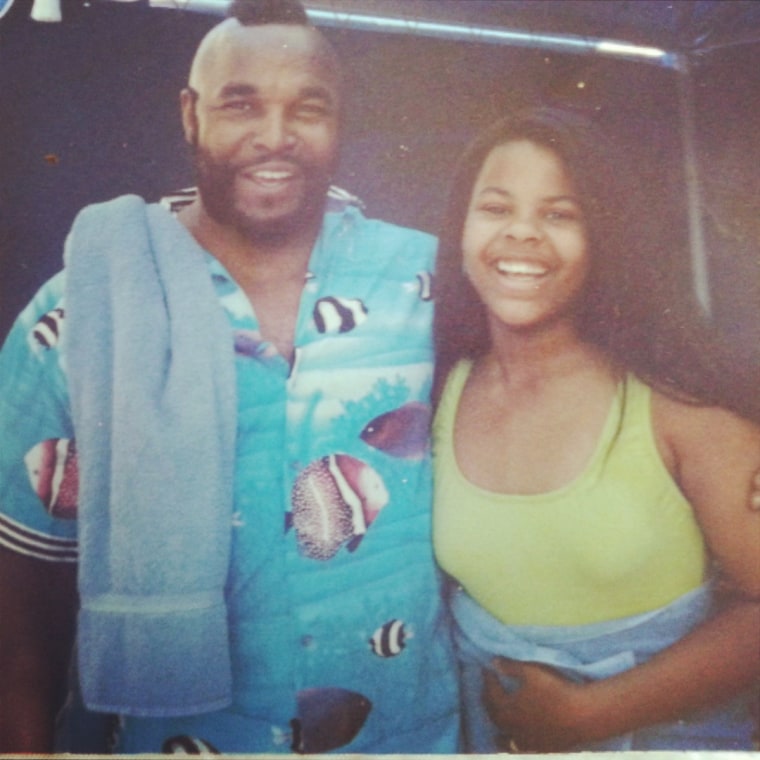

Clark’s father is the one and only “Mr. T.”

Mr. T, born Laurence Tureaud, is a bouncer turned professional wrestler, turned actor. Known for roles on the television series "The A-Team" and "Rocky III" Mr. T is arguably one of the most oversized pop culture personalities of the 80s.

Growing up the child of a celebrity, Clark learned from a young age to make light of unusual situations--like watching a coked up Hulk Hogan accidentally crash through your dining room table over Thanksgiving dinner.

“I always thought it was funny. My dad had on gold chains and everyone else’s dad had on a suit,” said Clark. “Of course I know it wasn’t normal.”

Recently Clark stood in front of over 600 people in a room as resplendent as her father’s once trademark gold chains. Clark was there to tell a story.

Clark was one of ten writers who won the Moth GrandSLAM, an annual competition held by The Moth, a non-profit dedicated to the art of storytelling. Founded by writer George Dawes Green in 1997, The Moth hosts a popular radio program as well as numerous live, storytelling events and competitions.

GrandSLAM winners tell a shorter version of their winning story at the Moth’s annual fundraiser in New York City, The Moth Ball. (The night also honored comedian Louis C.K. who regaled the crowd with a tale of traveling Russia alone at age 25.)

Clark recounted the time her mother, Phyllis Clark, tried to strangle her teacher for claiming that Clark couldn’t keep up with the other students in her Lake Forest class. A good story, certainly one that embodied this year’s theme: conflict.

Most of Clark’s comedy and stories are about her own life.

There was the time she sent “probably the filthiest text message you could ever think of” to ‘Dad’ instead of ‘Dave.’ After realizing her 4 A.M. mistake Clark turned off her phone in fear. When she finally did pick up her father curtly asked how she was, neglecting to mention the text. They never spoke of it. The call was one of few they share each year.

“We talk maybe once or twice a year. We’re not super close since I moved out,” said Clark. “He wants me to be a nice teacher and get married and have kids. [My dad] doesn’t want me to do entertainment at all so he hasn’t come to any of my shows before but he’s aware that I do it.”

Despite her father’s wishes Clark has wanted to go into entertainment since she was little.

“I always wanted to be the center of attention,” said Clark. “It’s weird, I don’t think most people know this but my dad is pretty shy when he’s not on camera. I was never like that…to be honest with you, I just wanted to be famous.”

Clark is the first to admit that her father’s notoriety helped her initially.

“People at first book me because they want to see what I look like or what I’ll talk about on stage,” said Clark. “A lot of my peers think it’s an unfair advantage. But [Mr. T] being my dad can only get me in the door. You still have to be funny. They’re not going to keep putting you on stage because of who you’re related to.”

Clark is a regular on Chicago’s competitive stand-up comedy circuit, has performed across the country, and also hosts a morning radio show in Chicago. Perhaps what's most impressive is that she’s done so with a permanence of selfhood rivaled only perhaps by her father’s hairstyle—which he’s maintained in a West African Warrior Mandinka cut since 1977. Clark doesn’t cater to what may be expected of her as a female or African-American comedian.

My dad is pretty shy when he’s not on camera. I was never like that…to be honest with you, I just wanted to be famous.

“It bothers me, men will be on stage and talk about everything. They’ll talk about sports, news, relationships, everything. Women tend to just stick with the relationship stuff and I didn’t want to be like that. I didn’t want to go up there and talk about my period,” said Clark.

Clark tries to avoid delving in to politics when she’s on stage. But she does approach issues like race in a refreshingly honest way.

“People tell me they don’t see color and I’m like are you joking? You know what race I am. You see me. That’s fine. Just don’t shoot me because of it.”

Clark credits working with special needs students as teaching her life is better when you don’t worry about what other people think and just have fun. And that’s exactly what she intends to do.

Going forward Clark plans to continue doing stand-up, storytelling, radio programs and perhaps some guest appearances on TV shows.

Standing on stage Tuesday night Clark was the only African-American GrandSLAM winner. But as she stepped forward to that didn’t seem to matter. She was no longer defined by her race or gender. She was no longer Mr. T’s daughter or a teacher turned comedian. She was a human being telling a story.

“I want to say what I really feel. For me comedy is a relief. It’s the only time in my day that I don’t have to act like Mary sunshine,” said Clark. “It’s like ‘ahhh’ I can relax, take my shoes off and be honest.”