After years of passing for Black, Rachel Dolezal's truth was very suddenly exposed in 2015.

Living in obscurity in Spokane, Washington, the head of the local chapter of the NAACP was forced to resign after her story was unraveled by a local news reporter who asked her point blank, "Are you African American?"

Dolezal didn't have an answer. She infamously left the frame, caught off guard. In the media frenzy that followed, Dolezal admitted that while she was born to Caucasian parents, she identified as a Black woman.

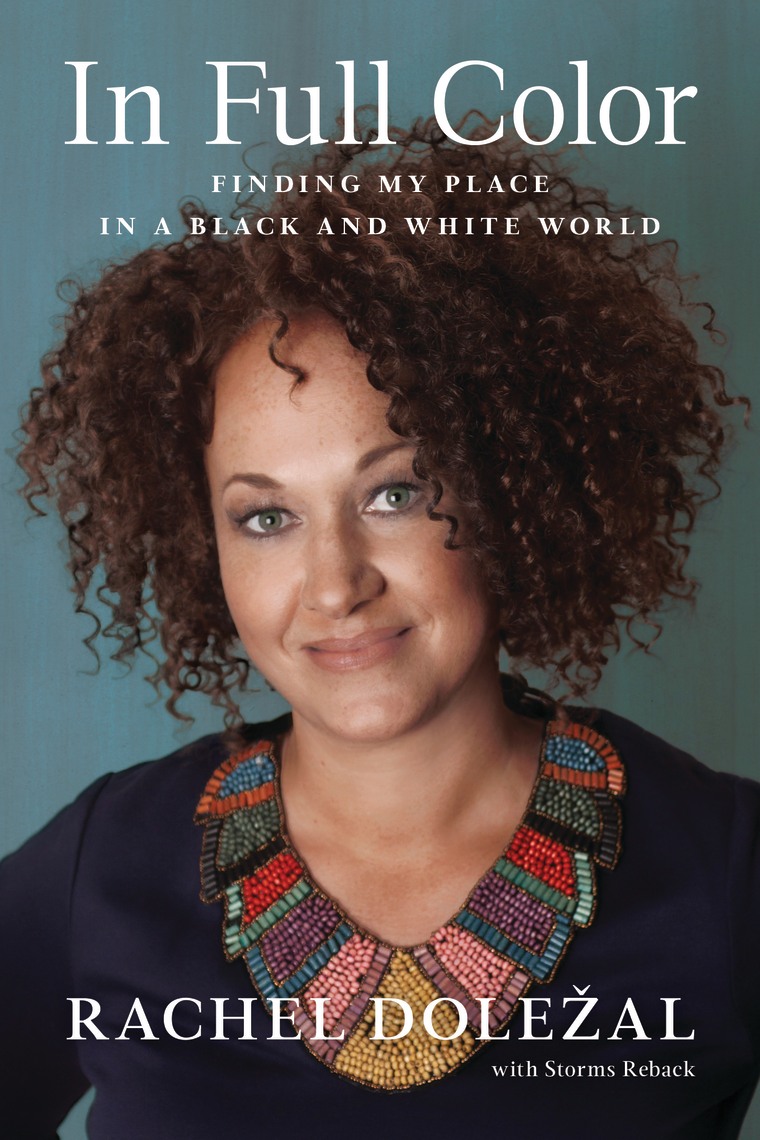

In her new memoir, "In Full Color: Finding My Place in a Black And White World," Dolezal provides some context about how a challenging upbringing shaped her search for identity as a Black or trans-Black woman.

"In order to really move toward what people really think of as some sort of Utopian post-racial society or somehow to really challenge the racial hierarchy, we’re going to have to allow some fluidity," she told NBCBLK.

Adamant that her racial fluidity is not equivalent to putting on a costume, she continued: "The color line can’t just forever be ingrained in some kind of one drop rule kind of Jim Crow sense."

NBCBLK caught up with Rachel Dolezal to talk about living as a Trans-Black woman, how her identity challenges white supremacy, and why she just couldn't be a white ally. Here is an edited and condensed transcript of the conversation.

How do you define 'Black' and 'Blackness'?

Well I think that in America, even though race is a social construct, I mean, we say this in theory, but I think a lot of people don’t believe that it really is. And so it’s still a very racialized society. And so there’s a line drawn in the sand. And there’s a Black and white divide and I stand unapologetically on the Black side of that divide with my own internal sense of self and my values, and with my sons and my sister and with the greater cause of really undoing the myth of white supremacy.

Would you have done anything differently when you’re looking back at how everything unfolded? You have received such a backlash, it has really affected your personal life, your financial well-being?

Well I wish that I could have had the chance to tell my whole story and introduce myself to the world instead of being introduced by others in a very negative connotation. So the oppositional people really came out with this narrative of a fraud, a liar and a con and all this kinda stuff before I had a chance to say, "Hello, my name is Rachel and this is who I am."

So I think it just kinda steamrolled and got so much momentum of negativity where my life just got shaped by that, and people’s perceptions of me were shaped by that. And I knew very quickly that I wasn’t going to be able to really describe my experience in full context in an interview and so I really needed to do that in book form.

Do you wish that you had maybe addressed this sooner in your life, or come forward to say, 'I identify as Black — I am a white woman but I identify as Black,' and start building that as part who you are very publicly.

Well I did, and for people who read the book you can kind of go walk through that journey. The funny thing is that when I was asserting that in college, for example, people were constantly — when I was like, “I was born to white parents,” people are like, “What are you?” and I would tell this long story, which people’s eyes would glaze over and they didn’t really wanna hear all that. But also the response would always be like, “No, you know you’re part Black.”

So as long as I was trying to explain my white parents and my upbringing, and everything, I was constantly being told that I was Black and that I was Blacker than white and all these kind of things. And even like, accused for passing for white. So I just got kind of tired of explaining because it was not helping. People would argue with me as if they knew my identity better than me. And that's still happening now.

I know last time, I think the term transracial, trans-Black was discussed. How do you define — do those terms come into the way you define yourself?

Absolutely, I think there are too few people — we don’t have the vocabulary to express racial fluidity. But I do like the term trans-Black that Melissa Harris Perry suggested because it does kinda cover the "I wasn’t born this way but this is who I really am" component. But "transracial" it almost sounds like I’m neutral, and I’m not neutral on political and social issues.

So trans-Black would be one way to describe —

Right, if I was allowed a more complex term, I would say I’m a pan-African, pro-Black, bisexual, mother, activist, artist, you know that’s like too long. So trans-Black is quicker.

OK, wow. I have never heard you describe yourself in those terms as well. Bisexual, I mean is that a newer — is that also covered in your book?

I did touch on that. I mean the focus isn’t necessarily my sexual orientation for this book, but I think that you know I mean, I am fluid in my sexuality. You know, people ask me all the time, "Oh, does she only date only Black men?" or something. I guess it is kind of like out there. And I’ve dated women and men, Black and white, and, and Native. So, love is love.

You want to get back to activism. What do you hope to do exactly?

I would love to get back to really focusing on the five game-changer issues that I was working on; criminal justice reform, education reform, economic sustainability, healthcare, and political representation.

I think definitely criminal justice and police brutality and public safety issues are probably one of the top as is education.

Do you think you could be as effective in these areas — fighting for social justice, raising your Black sons — as a white woman? There are other white women who are fighting for social justice, who are raising children of color. You know, do you think you could have been more effective as an ally, instead of as a Black woman?

Right, I really believe that, you know, we each need to be true to ourselves and that's the best path, like to be true to who you are.

I said I tried the "ally path" in my earlier young adulthood, I mean because I felt like I was obligated by everybody else’s definitions to really assert that this is how I was born this is therefore who I am. I felt kind of fated to that.

And you know, I did a lot of work but it wasn’t as much in harmony with me being seen and understood for who I am, and that just kind of all synchronizing, in my life.

You’re in a unique position because you, you know, grew up white, lived as a white woman, you are now, you identify as Black. How can you help white people? I mean if you’re, I know that part of your mission is, you partly wrote this book in a way to move the conversation on race. How do white people come into play?

Right, well I think it's undisputed that there’s still a lot of favor towards people who identify as white in Western societies and there’s still a stranglehold on power and privilege, by white people and I hope that my book challenges that. I hope that people kind of think twice about just the very idea that white is more beautiful, or more superior or smarter or better.

Related: Rachel Dolezal Answers 8 Facebook Questions

I’ve got a lot of opposition from people who who are very tightly and very closely and very kind of consciously aware of aligning with white supremacy ideals and they accuse me of committing white genocide and all these kind of things, you know. It’s like, I’m running the white bloodline in my family and kind of like butchering the idea of white beauty. So I think that we all need to really have the courage to confront our own convictions and understand like what we’re saying and why.

Do you feel that you can be kind of a unique, I don’t know, kind of liaison?

Yeah, kind of a bridge. I mean I do kind of feel somewhat caught in between a little bit, because, like kind of like a ping pong, getting slapped from both sides. But I guess that’s you know maybe useful for people to have something to bat around a little bit because people do want to talk about race and it’s something that, you know, we don’t talk enough in substantive ways. We kind always kind of talk about little surface stuff.

Do you feel betrayed at all by the Black community?

I wouldn’t say betrayed. I think just misunderstood by the way that my story was presented initially. It really pricked a lot of nerves and kind of sent people towards the direction of seeing me as the antithesis or the villain or the bad person.

I think we discussed it too, the element of white privilege and the element of being able to shift between these two worlds is an element of privilege. What are your thoughts on that at this time after reflecting on that?

So again, I think that it’s undisputed that white privilege exists, for sure. And is something that is pervasive in our society. I do feel like my identity actually challenges white supremacy, not reinforcing it.

It challenges white supremacy or white privilege? Because I’m just trying to get your position and your connection to that idea of having white privilege.

Right, it challenges white supremacy, but I think when people say, "You have white privilege and that’s why you can choose your identity," because that’s a common statement, we’re ignoring a massive amount of history, in which most often it’s actually been the opposite where Black and biracial people lived a white life. So maybe there’s again, light-skin privilege, white privilege, you know, there’s a range of privilege for sure, for maybe ethnically indeterminate people who have the “what are you” kind of question and then you have the option of asserting “I’m this or that” or letting that person identify you.

Right, I have the option of saying, “I’m biracial or I’m Black.” I don’t have the option of saying, 'I’m white' or do I?

Well, in some context, you may be seen as that. And Dr. Ann Morning talked about that in her book, “The Nature of Race,” which actually all of the books about race’s social construct that have been most influential in my life have been written by Black women: “The Nature of Race,” “Fatal Invention,” “Race in North America: Origin and Evolution of a Worldview.”

So all of those women, even Allison Hobbs, have chosen exile, talking about the history of racial passing in America. All those Black women have discussed the fluidity across the color lines in their own families, because three of those women were biracial as well and discussed how their parents and grandparents have moved in and out of those worlds and about why the dichotomy, why the binary still in 2017.

As far as the issues that are going on right now, what do you think is the most important thing that the administration should be focusing on?

Maybe, they should not focus on anything. [laughs] Maybe they can take a break and four years later, we can pick things back up.

It just seems like during [President Donald] Trump’s presidency, I expect race, power, and privilege is going to be amplified at every turn. I think it’s a little unpredictable what topics and issues that he’s going to make the biggest impact on with his administration, but from the attorney general, just a lot of Cabinet is really so disappointing. Once again, we have a white male, rich white male, in our power structure.

You have a one-year-old son. How has your life changed since bringing him into this world? What do you think you’ll tell your son about his cultural identity?

Well, I think that it’s important as a mother to support who our children are, and you kind of notice that as they grow and develop, whether it’s gender or sexual orientation, culture, the music that they want to listen to, the food that they like, so I’ll just be constantly encouraging him and guiding him toward what resonates with him. And he’s one, so right now, what resonates with him are toys and gadgets and buttons.

We have to talk hair. Your hair looks good. Did you do your hair?

I did. I actually had to give a plug: Boho Exotic Studios. My girl, she sent me two bundles, and I lightened and installed it.

You’re still doing hair.

Still doing hair.

Any final thing that you would like to add?

No, I just hope people read the book and really consider it for what’s in the book as the whole story. Little bits have come out as, you know, I’ve been called a liar and my parents have said they have the truth. But I think both were actually true.

I was born white, but I have an authentic Black identity and the book kind of develops that whole context of, how did that happen? What were all the steps along the way?